Draft USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 9: Waivers

1

Part B – Extreme Hardship DRAFT

Purpose

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) is issuing draft extreme hardship policy

guidance for public comment. This guidance clarifies how USCIS would make extreme hardship

determinations once the guidance is finalized.

Background

Admissibility is generally a requirement for admission to the United States, adjustment of

status, and other immigration benefits. Several INA provisions, however, authorize

discretionary waivers of particular inadmissibility grounds for those who demonstrate “extreme

hardship” to qualifying relatives, such as specified U.S. citizen or LPR family members.

Policy Highlights

The draft guidance:

Describes which waivers require a showing of extreme hardship.

Explains that an applicant has established extreme hardship to a qualifying relative if he or

she is able to show that it is reasonably foreseeable that the qualifying relative would

either relocate or remain in the United States, and that it is more likely than not that

the relocation or separation would result in extreme hardship.

Explains that the hardship must be of great suffering or loss, and that such hardship has to

be greater than that usually encountered as a result of denial of admission or removal.

Clarifies that extreme hardship is dependent on the individual circumstances of each

particular case.

Lists factors that may be considered when making an extreme hardship determination.

Explains special circumstances that would often weigh heavily in favor of a finding of

extreme hardship to a qualifying relative.

Clarifies that factors, individually or in the aggregate, can be sufficient to meet the

extreme hardship standard.

Clarifies that hardship to two or more qualifying relatives may be considered “extreme” in

the aggregate, if there is no single qualifying relative whose hardship alone is severe

enough to be found “extreme.”

Draft USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 9: Waivers

2

Part B – Extreme Hardship DRAFT

Chapter 1. Purpose and Background ....................................................................................... 3

Chapter 2. General Considerations, Interpretations, and Adjudicative Steps ........................ 4

A. General Considerations ................................................................................................... 4

B. Interpretations ................................................................................................................. 5

C. Adjudication Steps ........................................................................................................... 8

Chapter 3. Qualifying Relative ............................................................................................... 10

A. Establishing the Relationship to the Qualifying Relative ............................................... 10

B. Effect on Extreme Hardship if Qualifying Relative Dies ................................................. 10

C. Effect of Hardship Experienced by a Person who is not a Qualifying Relative .............. 12

Chapter 4. Extreme Hardship Factors.................................................................................... 12

A. Overview ........................................................................................................................ 12

B. Common Consequences of Inadmissibility .................................................................... 13

C. Examples of Factors that Might Support Finding of Extreme Hardship ........................ 13

D. Special Circumstances that Strongly Suggest Extreme Hardship .................................. 17

Chapter 5. Extreme Hardship Determinations ...................................................................... 25

A. Evidence ......................................................................................................................... 25

B. Burden of Proof and Standard of Proof ......................................................................... 26

Chapter 6. Discretion ............................................................................................................. 27

Draft USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 9: Waivers

3

Chapter 1. Purpose and Background

This Part offers guidance concerning the adjudication of applications for those discretionary

waivers of inadmissibility that require showings of “extreme hardship” to certain U.S. citizen or

lawful permanent resident (LPR) family members of the applicant.

1

Admissibility is generally a requirement for admission to the United States, adjustment of

status, and other immigration benefits.

2

Several provisions of the Immigration and Nationality

Act (INA),

3

however, authorize discretionary waivers of particular inadmissibility grounds for

those who demonstrate “extreme hardship” to specified U.S. citizen or LPR family members

(referred to here as “qualifying relatives”). Each of these provisions conditions a waiver on both

a finding of extreme hardship to a qualifying relative and the more general favorable exercise of

discretion. All of these waiver applications are adjudicated by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration

Services (and in some cases by the Department of Justice’s Executive Office for Immigration

Review).

4

The various statutory provisions specify different sets of qualifying relatives and permit waivers

of different inadmissibility grounds. They include:

INA 212(a)(9)(B)(v) – This provision can waive the three-year and ten-year inadmissibility

bars for unlawful presence.

5

Eligible qualifying relatives include the applicant’s U.S.

citizen or LPR spouse or parent.

6

INA 212(h)(1)(B) – This provision can waive inadmissibility for crimes involving moral

turpitude, multiple criminal convictions, prostitution and commercialized vice, and

1

Several other discretionary waivers and other forms of discretionary relief are available upon showings of

extreme hardship to the applicants themselves. These include waivers of inadmissibility under INA 212(i)(1)

(waiver of fraud-related inadmissibility for VAWA self-petitioners), INA 216(c)(4)(A) (waiver of requirements for

removing conditions on lawful permanent resident status), and suspension of removal and cancellation of removal

under Section 203 of Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central America Relief Act (NACARA), Title II of Pub. L. 105-100,

111 Stat. 2160, 2196 (November 19, 1997). See 8 CFR 240.64(c) and 8 CFR 1240.64(c). This Part does not address

the adjudication of applications for those remedies to the extent that they relate to extreme hardship to the

applicant himself or herself. It also does not address those discretionary relief provisions that require a showing of

greater hardship. See INA 212(e) (“exceptional hardship” waiver of two-year foreign residence requirement for

certain exchange visitors) and INA 240A(b)(1)(D) (“exceptional and extremely unusual hardship” generally required

for cancellation of removal Part B).

2

See INA 212(a) and INA 245(a).

3

See Immigration and Nationality Act, Pub. L. 82-414, 66 Stat. 163 (June 27, 1952), as amended.

4

See 6 U.S.C. 271(b). See Delegation No. 0150.1, “Delegation to the Bureau of Citizenship and Immigration

Services” II, Z (June 5, 2003).

5

See INA 212(a)(9)(B)(i).

6

Applicants for provisional waivers of unlawful presence should check the form instructions, as the process may be

limited to applicants with certain qualifying relatives.

Draft USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 9: Waivers

4

certain serious criminal offenses for which the foreign national received immunity from

prosecution.

7

It can also waive inadmissibility for controlled substance convictions, but

only when the conviction was for a single offense of simple possession of 30 grams or

less of marijuana.

8

Eligible qualifying relatives include the applicant’s U.S. citizen or LPR

spouse, parent, son, or daughter.

INA 212(i)(1) – This provision can waive inadmissibility for certain types of immigration

fraud.

9

Eligible qualifying relatives include the applicant’s U.S. citizen or LPR spouse or

parent.

Chapter 2. General Considerations, Interpretations, and Adjudicative Steps

A. General Considerations

The purpose of the various statutory waiver provisions is to enable the relevant agencies (in this

case USCIS) to balance the competing policy considerations that affect whether a given foreign

national should be admitted to the United States. On the one hand, the fact situations to which

these waivers apply involve misconduct that Congress has found serious enough to render a

person inadmissible. On the other hand, by authorizing extreme hardship waivers Congress

created a specific exception for those cases in which the refusal of admission would result in

more than the usual level of hardship for specified U.S. citizen or lawful permanent resident

family members. Congress clearly intended the waiver to be applied with those sorts of family

unity and other humanitarian concerns in mind.

In deciding applications for any of these waivers, the officer exercises discretion at two stages

of the process. First, the determination of whether the alleged hardships are “extreme” is itself

a discretionary judgment.

10

Second, a finding of extreme hardship to a qualifying relative does

not guarantee approval of the waiver; the officer must still make a more general decision as to

whether the favorable exercise of discretion is merited.

11

At each of these two stages, the

7

See INA 212(a)(2)(A)(i), INA 212(a)(2)(B), INA 212(a)(2)(D), and INA 212(a)(2)(E).

8

See INA 212(a)(2)(A)(ii).

9

See INA 212(a)(6)(C)(i).

10

See Hamilton v. Holder, 680 F.3d 1024, 1027 (8th Cir. 2012) (holding extreme hardship determination

discretionary and therefore not subject to judicial review). See Romero-Torres v. Ashcroft, 327 F.3d 887 (9th Cir.

2003) (same). See Gonzalez-Oropeza v. U.S. Att’y Gen., 321 F.3d 1331, 1332-33 (11th Cir. 2003) (same). The courts

retain jurisdiction to review “the purely legal and hence non-discretionary question” of whether a person qualifies

as a qualifying relative, Romero-Torres, 327 F. 3d at 890, and “whether … the correct discretionary waiver standard

[was applied] in the first instance,” Cervantes-Gonzales v. INS, 244 F.3d 1001, 1005 (9th Cir. 2001). See Hamilton,

680 F.3d 1024, 1026 (8th Cir. 2012) (holding courts “retain jurisdiction over any ‘constitutional claims or questions

of law’”).

11

See Chapter 6, Discretion [9 USCIS-PM B.6].

Draft USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 9: Waivers

5

officer bases his or her discretionary determination on the totality of the relevant evidence in

the individual case.

12

The burden of proof lies with the applicant to demonstrate both that he or she meets the

statutory requirements, including extreme hardship, and that he or she merits a favorable

exercise of discretion.

13

The applicant must prove the requisite extreme hardship by a

preponderance of the evidence. This means the applicant must prove that it is more likely than

not that a denial of admission would result in extreme hardship to the qualifying relative.

14

The

applicant also has the burden of demonstrating that he or she merits a favorable exercise of

discretion.

USCIS recognizes that at least some degree of hardship to the qualifying relative exists in most,

if not all, cases in which the principal immigrant is denied admission. Thus, to be considered

“extreme,” the hardship must exceed that which is usual or expected.

15

At the same time, the

hardship need not be unique;

16

nor is “extreme hardship” as demanding as the “exceptional

and extremely unusual hardship” standard generally applicable to cancellation of removal Part

B.

17

B. Interpretations

The phrase “extreme hardship” is not defined in the INA or in any decisions of the Board of

Immigration Appeals (BIA) or the federal courts. Rather, as the U.S. Supreme Court held in INS

v. Jong Ha Wang, “[t]hese words are not self-explanatory, and reasonable men could easily

differ as to their construction. But the [INA] commits their definition in the first instance to the

12

See Matter of Cervantes-Gonzalez, 22 I&N Dec. 560, 566 (BIA 1999), aff’d, Cervantes-Gonzales v. INS, 244 F.3d

1001 (9th Cir. 2001). See Matter of Ngai, 19 I&N Dec. 245 (BIA 1984). See Matter of Shaughnessy, 12 I&N Dec. 810

(BIA 1968).

13

See INA 291 (providing that burden is on applicant for admission to prove he or she is “not inadmissible”). See

Matter of Mendez-Moralez, 21 I&N Dec. 296, 299 (BIA 1996) (holding that applicant for INA 212(h)(1)(B) waiver has

burden of showing that favorable exercise of discretion is warranted, “as is true for other discretionary forms of

relief”). See 8 CFR 212.7(e)(7) (provisional INA 212(a)(9)(B)(v) waivers) and INA 240(c)(4)(A) (in removal

proceedings, the applicant for relief has the burden of proving that he or she is statutorily eligible and merits a

favorable exercise of discretion).

14

See Matter of Chawathe, 25 I&N Dec. 369, 376 (AAO 2010). See Fisher v. Vassar College, 114 F.3d 1332, 1333-34

(2nd Cir. 1997) (holding that in other contexts “preponderance of the evidence” means more likely than not).

15

See 8 CFR 1240.58(b) (for purposes of the former suspension of deportation provision, the hardship must go

“beyond that typically associated with deportation”).

16

See Matter of L-O-G-, 21 I&N Dec. 413, 418 (BIA 1996).

17

See Matter of Andazola-Rivas, 23 I&N Dec. 319, 322, 324 (BIA 2002) (holding the “exceptional and extremely

unusual hardship” standard to be “significantly more burdensome than the ‘extreme hardship’ standard” and

intimating that the applicant “might well” have prevailed under the latter standard even though she failed the

former standard). See Matter of Monreal-Aguinaga, 23 I&N Dec. 56, 59-64 (BIA 2001) (same).

Draft USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 9: Waivers

6

Attorney General [and the Secretary of Homeland Security] and [their] delegates …”

18

Thus,

“[t]he Attorney General [and the Secretary of Homeland Security] and [their] delegates have

the authority to construe ‘extreme hardship’ narrowly should they deem it wise to do so.”

19

Conversely, “[a] restrictive view of extreme hardship is not mandated either by the Supreme

Court or by [the BIA] case law.”

20

1. Separation versus Relocation

With respect to the requirement that the refusal of the applicant’s admission “would result in”

extreme hardship to a qualifying relative, there are two factual scenarios to consider. The

qualifying relative might either relocate overseas with the applicant or remain in the United

States separated from the applicant. In either scenario, depending on all the facts of the

particular case, the refusal of admission might or might not result in the qualifying relative

experiencing extreme hardship.

Interpreting the phrase “would result in,” and applying the preponderance of the evidence

standard,

21

USCIS has determined that the applicant may satisfy the extreme hardship

requirement by showing that either:

It is reasonably foreseeable that the qualifying relative would relocate and more likely

than not that the relocation would result in extreme hardship; or

It is reasonably foreseeable that the qualifying relative would remain in the United

States and more likely than not that the separation would result in extreme hardship.

An applicant may also satisfy the extreme hardship requirement by showing that both the

relocation and separation scenarios could be reasonably foreseeable and would more likely

than not result in extreme hardship.

Importantly, it is not appropriate for an officer to base this determination on his or her personal

moral view as to whether a particular qualifying relative ought to relocate overseas. U.S.

citizens and lawful permanent residents typically have much at stake in continuing to live in the

United States; whether to do so at the cost of separation from a close family member is a highly

personal decision.

The statutory language “would result in” makes the relevant inquiry predictive, not normative.

Thus, if the officer finds, based on the totality of the evidence, that relocation is reasonably

18

See 450 U.S. 139, 144 (1981) (per curiam).

19

See INS v. Jong Ha Wang, 450 U.S. 139, 145 (1981) (per curiam).

20

See Matter of Pilch, 21 I&N Dec. 627, 630 (BIA 1996). See Matter of L-O-G-, 21 I&N Dec. 413, 418 (BIA 1996).

21

See Section A, General Considerations [9 USCIS-PM B.2(A)].

Draft USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 9: Waivers

7

foreseeable, then the next inquiry is whether the relocation would result in the qualifying

relative suffering extreme hardship. If instead the officer finds, based on the totality of the

evidence, that separation is reasonably foreseeable, then the next inquiry is whether the

separation would result in his or her suffering extreme hardship.

22

Special considerations might arise if the qualifying relative is a child.

23

In that particular context,

a parent who asserts that his or her child will remain in the United States should generally be

expected to explain the arrangements for the child’s care and support. The failure to provide a

credible plan for the care and support of the child might indicate that in actuality the child

remaining behind in the United States is not a realistic scenario.

24

Moreover, if the parent

represents that the child will be left behind, the officer might require the parent to state that

understanding in an affidavit.

25

An affidavit is not required, however, if the parent represents

that the child will be left behind in the care of the other parent, even if that other parent is

unlawfully present.

26

Being left in the care of the other parent might still result in extreme

hardship, depending on the totality of the circumstances.

2. Aggregating Hardships

To establish extreme hardship, it is not necessary to demonstrate that a single hardship, taken

in isolation, rises to the level of “extreme.” Rather, any relevant hardship factors “must be

considered in the aggregate, not in isolation.”

27

Thus, even if no one factor individually

constitutes extreme hardship, the officer “must consider the entire range of factors concerning

hardship in their totality and determine whether the combination of hardships takes the case

beyond those hardships ordinarily associated with deportation” (or, in this case, the refusal of

admission).

28

Even “those hardships ordinarily associated with deportation, … while not alone

22

For guidance on the evidence that may be relevant to the assessment of reasonable foreseeability, see Chapter

5, Extreme Hardship Determinations, Section B, Burden of Proof and Standard of Proof [9 USCIS-PM B.5(B)].

23

This is possible in cases of waivers of criminal grounds under INA 212(h)(1)(B).

24

See Matter of Ige, 20 I&N Dec. 880, 885 (BIA 1994) (holding that, for purposes of the former suspension of

deportation, neither the parent’s “mere assertion” that the child will remain in the United States nor the mere

“possibility” of the child remaining is entitled to “significant weight;” rather, the Board expects evidence that

“reasonable provisions will be made for the child’s care and support”). See Iturribarria v. INS, 321 F.3d 889, 902-03

(9th Cir. 2003) (finding that in suspension of deportation case, the petitioner could not claim extreme hardship

from family separation without evidence of the family’s intent to separate). See Perez v. INS, 96 F.3d 390, 393 (9th

Cir. 1996) (holding that agency properly required, as means of reducing speculation in considering extreme

hardship element in a suspension of deportation case, affidavits and other evidentiary material establishing that

family members “will in fact separate”).

25

See Matter of Ige, 20 I&N Dec. 885, at 885 (BIA 1994) (requiring such an affidavit in suspension of deportation

cases).

26

See Matter of Calderon-Hernandez, 25 I&N Dec. 885 (BIA 2012).

27

See Bueno-Carrillo v. Landon, 682 F.2d 143, 146 n.3 (7th Cir. 1982); accord Ramos v. INS, 695 F.2d 181, 186 n.12

(5th Cir. 1983).

28

See Matter of O-J-O-, 21 I&N Dec. 381, 383 (BIA 1996).

Draft USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 9: Waivers

8

sufficient to constitute extreme hardship, are considered in the assessment of aggregate

hardship.”

29

The applicant need show extreme hardship to only one qualifying relative. But even if there is

no single qualifying relative whose hardship alone is severe enough to be found “extreme,” it is

also sufficient if the hardship to two or more qualifying relatives adds up to extreme hardship.

30

Thus, if the applicant presents evidence of hardship to multiple qualifying relatives, the officer

should aggregate all of their hardships to decide whether the sum total adds up to extreme

hardship.

31

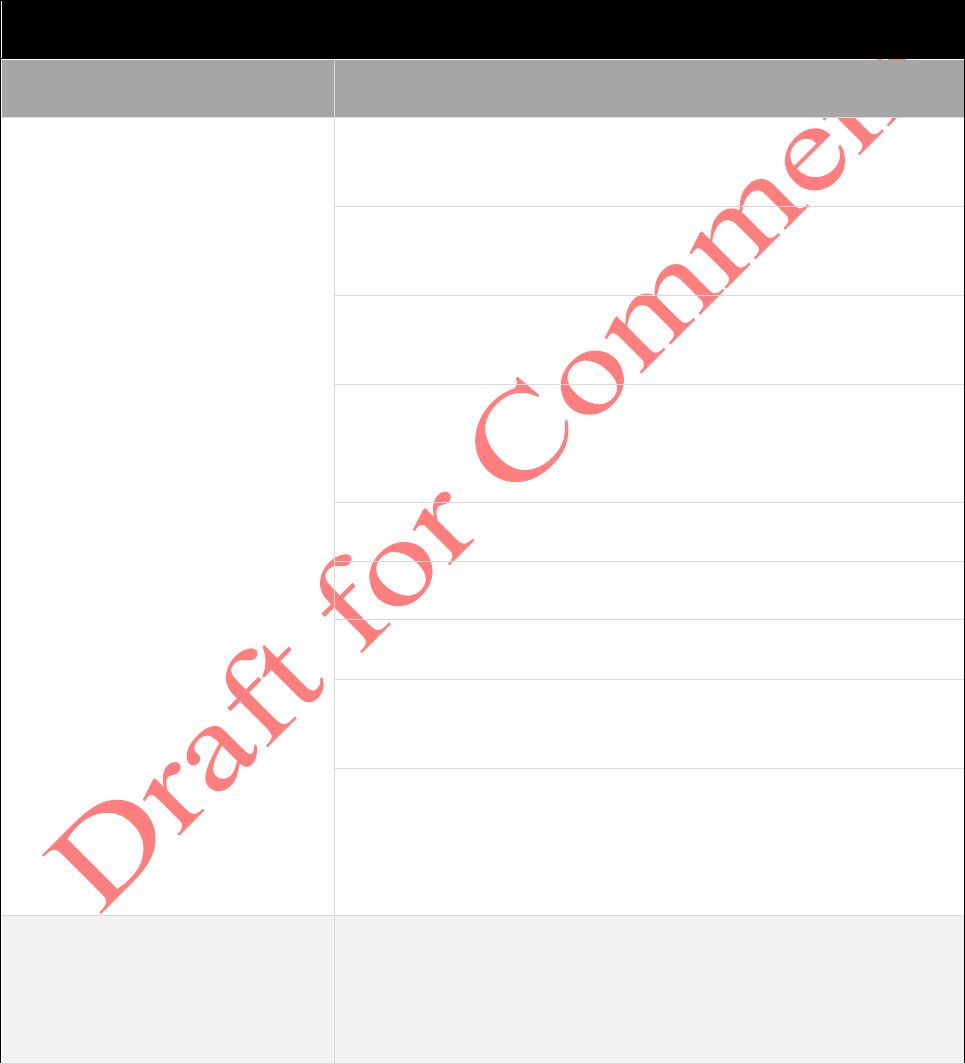

C. Adjudication Steps

The officer should complete the following steps when adjudicating a waiver application that

requires a showing of extreme hardship to a qualifying relative:

32

29

See Matter of O-J-O-, 21 I&N Dec. 381, 383 (BIA 1996). See Matter of Ige, 20 I&N Dec. 880, 882 (BIA 1994)

(“Relevant factors, though not extreme in themselves, must be considered in the aggregate in determining

whether extreme hardship exists.”).

30

See Watkins v. INS, 63 F.3d 844, 850 (9th Cir. 1995) (reversing BIA decision on ground it had failed to aggregate

the “professional and social changes” of the petitioner, who was a qualifying relative under the particular statute,

with the hardship to the applicant’s children, who were also qualifying relatives). See Prapavat v. INS, 638 F.2d 87,

89 (9th Cir. 1980) (holding that extreme hardship “may also be satisfied … by showing that the aggregate hardship

to two or more family members described in then 8 U.S.C. 1254(a)(1) is extreme, even if the hardship suffered by

any one of them would be insufficient by itself”), reheard, , 662 F.2d 561, 562-63 (9th Cir. 1981) (per curiam) (again

listing both hardships to the qualifying relative petitioners and hardships to their U.S. citizen child, holding that

these hardships “must all be assessed in combination,” and finding that the Board had erred in failing to do so).

See Jong Ha Wang v. INS, 622 F.2d 1341, 1347 (9th Cir. 1980) (“[T]he Board should consider the aggregate effect of

deportation on all such persons when the alien alleges hardship to more than one.”), rev’d on other grounds, 450

U.S. 139 (1981) (per curiam). These decisions all interpreted the former suspension of deportation provision. The

list of qualifying individuals (which included the petitioners themselves) whose extreme hardship sufficed under

that provision differed from the lists of qualifying relatives in the waiver provisions discussed here, but the

statutory language was identical in all other relevant respects (“result in extreme hardship to …”). Consequently,

the courts and the BIA have frequently relied on the suspension cases for aid in interpreting the similar language of

the waiver cases. See Hassan v. INS, 927 F.2d 465, 467 (9th Cir. 1991). See Matter of Cervantes-Gonzalez, 22 I&N

Dec. 560, 565 (BIA 1999), aff’d, Cervantes-Gonzales v. INS, 244 F.3d 1001 (9th Cir. 2001).

31

Even the aggregated hardships will not add up to extreme hardship if they include only those that the BIA has

held to be “common consequences.” For a list of those common consequences, see Chapter 4, Extreme Hardship

Factors, Section B, Common Consequences of Inadmissibility [9 USCIS-PM B.4(B)].

32

In most cases, there will already have been a finding of inadmissibility, either by the consular officer adjudicating

a visa application, or a USCIS officer adjudicating a related application, such as a Form I-485, Application to Register

Permanent Residence or Adjust Status. A formal finding of inadmissibility is not required in adjudicating a Form I-

601A, Application for Provisional Presence Waiver. The officer should identify all inadmissibility grounds and

confirm that the ground(s) may be waived. This chart assumes that the inadmissibility grounds have been

identified and that a waiver is available.

Draft USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 9: Waivers

9

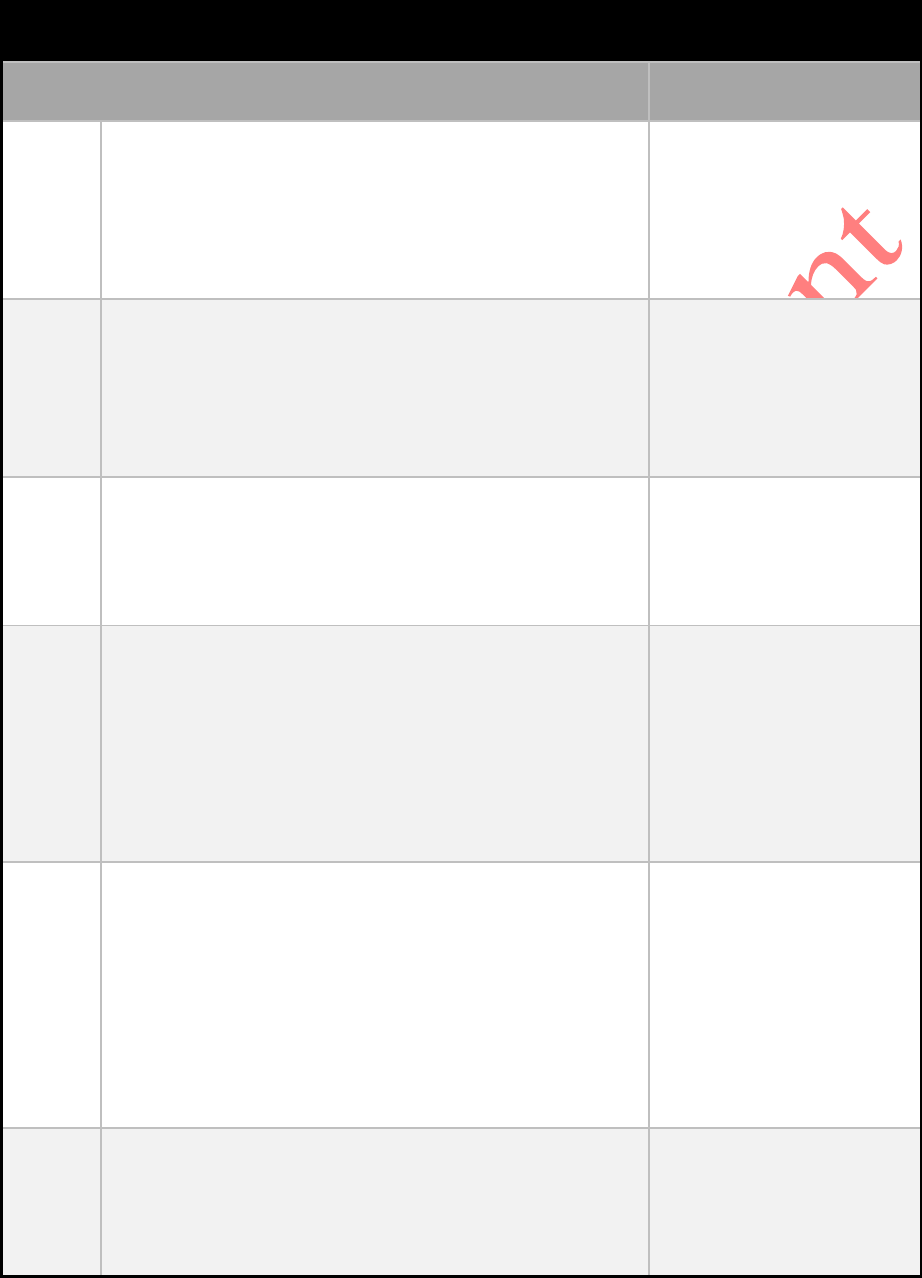

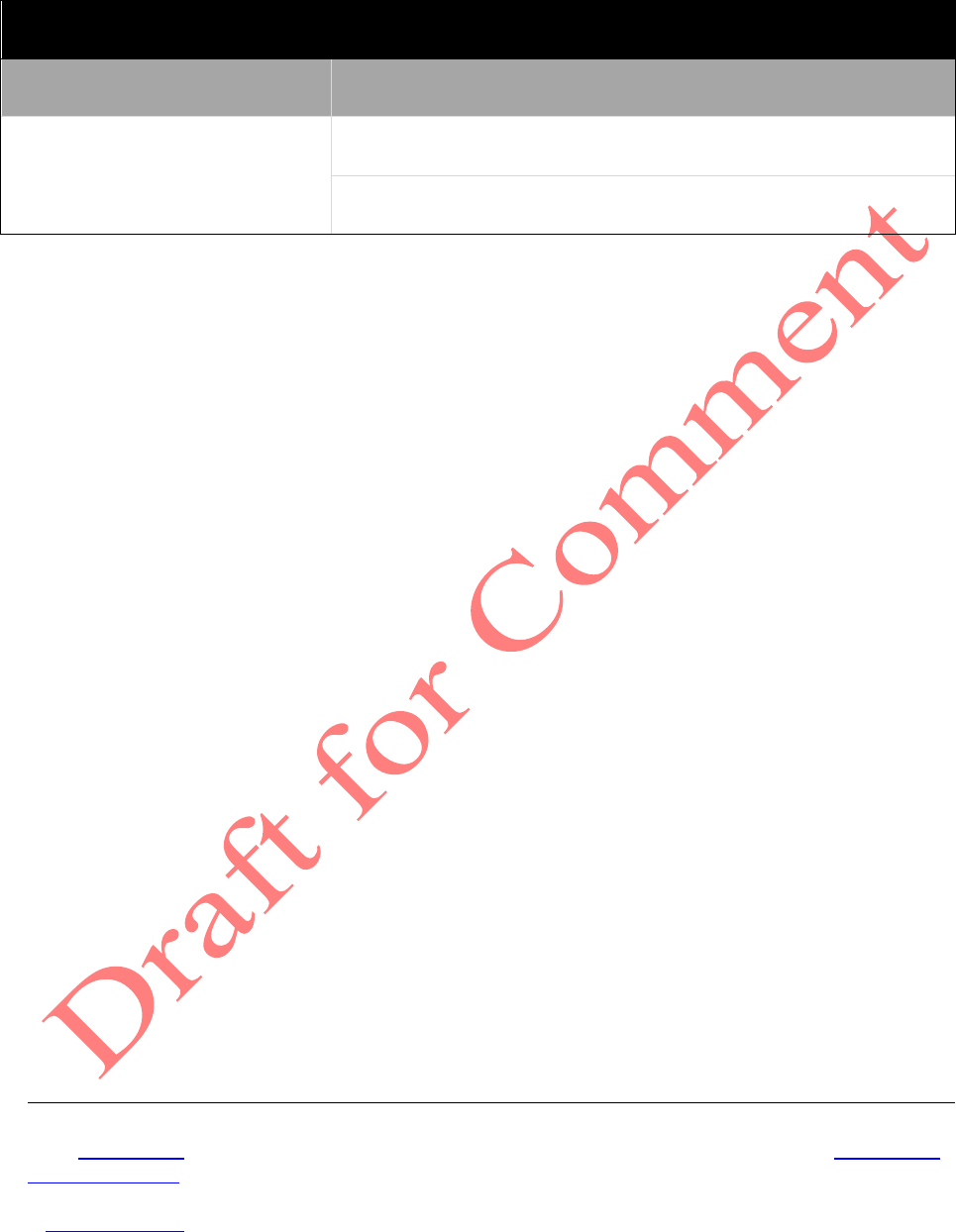

Adjudication Steps for Waivers Requiring Extreme Hardship to a Qualifying Relative

Adjudication Step

For More Information

Step 1

Confirm the waiver provision requires a showing of

extreme hardship to a qualifying relative.

See Chapter 1, Purpose

and Background

[9 USCIS-PM B.1]

Step 2

Identify each qualifying relative whose hardship

would be relevant under the applicable waiver

provision, and determine whether the applicant has

established the family relationship(s) to them.

See Chapter 3, Qualifying

Relative [9 USCIS-PM B.3]

Step 3

Determine whether, if the waiver application were

denied, either relocation or separation (or both)

is/are reasonably foreseeable for each of the

qualifying relatives you have identified.

See Section B,

Interpretations,

Subsection 1, Separation

versus Relocation [9

USCIS-PM B.2(B)(1)]

Step 4

Based on the determination in step 3 and the

evidence submitted, evaluate the present and future

hardships that each qualifying relative would more

likely than not experience if the waiver request were

denied.

See Chapter 4, Extreme

Hardship Factors [9

USCIS-PM B.4]

See Chapter 5, Extreme

Hardship Determinations

[9 USCIS-PM B.5]

Step 5

Determine whether it is more likely than not that, in

the aggregate, the hardships to the qualifying

relatives add up to extreme hardship.

See Chapter 4, Extreme

Hardship Factors [9

USCIS-PM B.4]

See Chapter 5, Extreme

Hardship Determinations

[9 USCIS-PM B.5]

Step 6

If extreme hardship is not found, deny the

application. If extreme hardship is found, exercise

further discretion to determine whether, based on

the totality of the facts of the individual case, the

See Chapter 6, Discretion

[9 USCIS-PM B.6]

Draft USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 9: Waivers

10

Adjudication Steps for Waivers Requiring Extreme Hardship to a Qualifying Relative

Adjudication Step

For More Information

waiver should be granted.

Chapter 3. Qualifying Relative

A. Establishing the Relationship to the Qualifying Relative

An officer must verify that the relationship to a qualifying relative exists. The qualifying relative

need not be the visa petitioner, but if it is, an officer may use the approval of the Petition for

Alien Relative (Form I-130) as proof that the qualifying relationship has been established.

33

If the applicant’s relationship to the qualifying relative has not already been established

through a prior approved petition, the officer must otherwise verify that the relationship to the

qualifying relative exists. Applicants should include in the waiver application primary evidence

that supports the relationship, such as marriage certificates, birth certificates, adoption papers,

or other court documents, such as paternity orders or orders of child support.

If such primary

evidence does not exist or is unavailable, the applicant should explain why and submit

secondary evidence of the relationship, such as school records, records of religious or other

community institutions, or affidavits from those with personal knowledge of the relevant

facts.

34

If the initial submission does not include primary evidence of the relationship, and the

applicant fails to explain why such evidence does not exist or is unavailable or does not include

secondary evidence of the relationship, the officer should issue a Request for Evidence (RFE).

If the applicant claims that all or part of the qualifying relative’s hardship will result from the

hardship to be suffered by that qualifying relative’s non-qualifying family member, the officer

should ensure that the evidence establishes the claimed relationships.

35

If such evidence is

missing, the officer should issue an RFE.

B. Effect on Extreme Hardship if Qualifying Relative Dies

Ordinarily the qualifying relative who suffers the extreme hardship must be alive at the time

the waiver application is filed and adjudicated. But there is one exception: Under INA 204(l),

certain petitions are deemed to remain valid despite the death of the petitioning qualifying

33

An officer who has concerns about the approved Form I-130 should consult with a supervisor.

34

See 8 CFR 103.2(b)(2)(i).

35

See Section C, Effect of Hardship Experienced by a Person who is not a Qualifying Relative [9 USCIS-PM B.3(C)].

Draft USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 9: Waivers

11

relative (or the death of the principal beneficiary in the case of a derivative beneficiary). These

petitions include those filed for:

Immediate relatives;

Family-sponsored immigrants; and

Designated family members of family-sponsored immigrants, employment-based

immigrants, refugees, asylees, VAWA self-petitioners, and T and U nonimmigrants.

For the petition to survive the death of the qualifying relative under INA 204(l), the petition has

to have been pending or approved before the death of the qualifying relative, the beneficiary

has to have resided in the United States at the time of that death, and the beneficiary has to

continue to reside in the United States. Officers should review the INA 204(l) guidance, when

applicable, for the precise requirements.

36

If the above conditions are met, INA 204(l)(1) provides that “related applications” similarly

survive the death of the qualifying relative. The USCIS position is that “related applications”

include the corresponding applications for waivers of inadmissibility. Thus, a foreign national

who meets the requirements of INA 204(l) may continue to apply for the waiver even though

the qualifying relative has died. Further, if the waiver requires that the qualifying relative suffer

extreme hardship, USCIS treats the petitioner’s or principal beneficiary’s death as the functional

equivalent of a finding of extreme hardship to a qualifying relative – provided that the decedent

is also one of the qualifying relatives covered by the applicable waiver provision. In such a case

the death of the qualifying relative should be noted in the decision.

37

The same is true for the widow(er)s of U.S. citizens. When a U.S. citizen files a Petition for Alien

Relative (Form I-130) on behalf of his or her spouse, and the citizen dies while the petition is

pending or after it has been approved (and certain other conditions are met), USCIS deems the

I-130 to be automatically converted to a self-petition.

38

Nonetheless, if the widow(er) meets

the residence requirements in INA 204(l), then INA 204(l) preserves the widow(er)'s ability to

have a waiver application approved as if the now deceased citizen had not died. This is the case

even if the petition later reverts to a Form I-130 because of the widow(er)’s remarriage.

39

36

See USCIS Policy Memorandum, Approval of Petitions and Applications after the Death of the Qualifying Relative

under New Section 204(l) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, PM-602-0017 (Dec. 16, 2010).

37

See USCIS Policy Memorandum, Approval of Petitions and Applications after the Death of the Qualifying Relative

under New Section 204(l) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, PM-602-0017 (Dec. 16, 2010), p. 9.

38

Under INA 201(b)(2)(A)(i). See Form I-360, Petition for Amerasian, Widow(er), or Special Immigrant.

39

See Williams v. DHS, 741 F.3d 1228 (11th Cir. 2014). USCIS applies this ruling nationwide.

Draft USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 9: Waivers

12

C. Effect of Hardship Experienced by a Person who is not a Qualifying Relative

Hardship to a non-qualifying relative,

40

by itself, does not meet the extreme hardship

requirement. In some cases, however, the hardship experienced by someone who is not a

qualifying relative (including the applicant) can itself be the cause of hardship to a qualifying

relative.

41

As one example, an applicant with a mental disorder shows that he would be relegated to living

in a psychiatric institution in his home country, where he would be unable to obtain the

necessary medical treatment. The applicant provides medical documentation and State

Department information on country conditions that corroborate his statements. The applicant’s

condition and prospective situation might show that denial of his admission would have a

significant emotional or financial impact on his U.S. citizen or LPR qualifying relative in the

United States. The officer may consider the impact of such medical and living conditions as a

factor when determining whether the qualifying relative would experience extreme hardship

upon separation from the applicant.

As another example, an officer should consider the emotional hardship that a parent would

experience from knowing that either separation or other consequences are causing hardship to

his or her non-qualifying child or other third party.

42

Such derivative hardship might or might

not rise to the level of “extreme,” but even if it does not, it is one of the hardship factors that

the officer should consider in determining whether the qualifying relative’s hardship, when

considered in the aggregate, would be extreme.

Chapter 4. Extreme Hardship Factors

A. Overview

The officer should consider any factor that the applicant presents as a potential hardship,

regardless of whether case law addresses the factor and regardless of whether the factor is

included in the lists below. The officer may also consider other factors relevant to the extreme

hardship determination that the applicant has not specifically presented, such as those

40

For example, hardship to the applicant’s child when the particular waiver provision lists only the applicant’s

spouse and parents as qualifying relatives.

41

See Contreras-Buenfil v. INS, 712 F.2d 401, 403 (9th Cir. 1983) (hardship to non-qualifying relative could cause

hardship to applicant, which would have sufficed under then-existing law). See Antoine-Dorcelli v. INS, 703 F.2d 19,

22 (1st Cir. 1983) (same). See Matter of Gonzalez Recinas, 23 I&N Dec. 467, 471 (BIA 2002) (“In addition to the

hardship of the United States citizen children, factors that relate only to the respondent may also be considered to

the extent that they affect the potential level of hardship to her qualifying relatives.”).

42

See Zamora-Garcia v. INS, 737 F.2d 488, 494 (5th Cir. 1984) (requiring, in suspension of deportation case,

“consideration of the hardship to the [qualifying applicant] posed by the possibility of separation from the [non-

qualifying third party children]”).

Draft USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 9: Waivers

13

addressed in Department of State (DOS) information on country conditions

43

or other U.S.

Government determinations regarding country conditions, including a country’s designation for

Temporary Protected Status (TPS).

Some of the factors listed below apply when the qualifying relative would remain in the United

States without the applicant. Other factors apply when the qualifying relative would relocate

abroad. Some of the factors might apply in either scenario.

B. Common Consequences of Inadmissibility

Common consequences of an applicant’s refusal of admission, in and of themselves, do not

warrant a finding of extreme hardship.

44

The BIA has held that these common consequences

include, but are not limited to, the following:

Family separation;

Economic detriment;

Difficulties of readjusting to life in the new country;

The quality and availability of educational opportunities abroad;

Inferior quality of medical services and facilities; and

Ability to pursue a chosen employment abroad.

Even though these common consequences alone would be an insufficient basis for a finding of

extreme hardship, they are still factors that must be considered when aggregating the total

hardships to the qualifying relative. When combined with other factors that might also have

been insufficient when taken alone, even these common consequences might cause the sum of

the hardships to reach the “extreme hardship” standard. For example, if a qualifying relative is

gravely ill, elderly, or incapable of caring for himself or herself, the combination of that

hardship and the common consequences of a refusal of the applicant’s admission might well

cause extreme emotional or financial hardship for the qualifying relative.

C. Examples of Factors that Might Support Finding of Extreme Hardship

43

See DOS Country Reports on Human Rights Practices and DOS Travel Warnings.

44

See Matter of Ngai, 19 I&N Dec. 245 (BIA 1984) and Matter of Shaughnessy, 12 I&N Dec. 810 (BIA 1968).

Draft USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 9: Waivers

14

Below is a list of factors that an applicant might present and that an officer would consider

when making extreme hardship determinations. This list is not exhaustive; circumstances that

are not on this list can also be the basis for finding extreme hardship. All hardship factors

presented by the applicant should be considered in making the extreme hardship

determination.

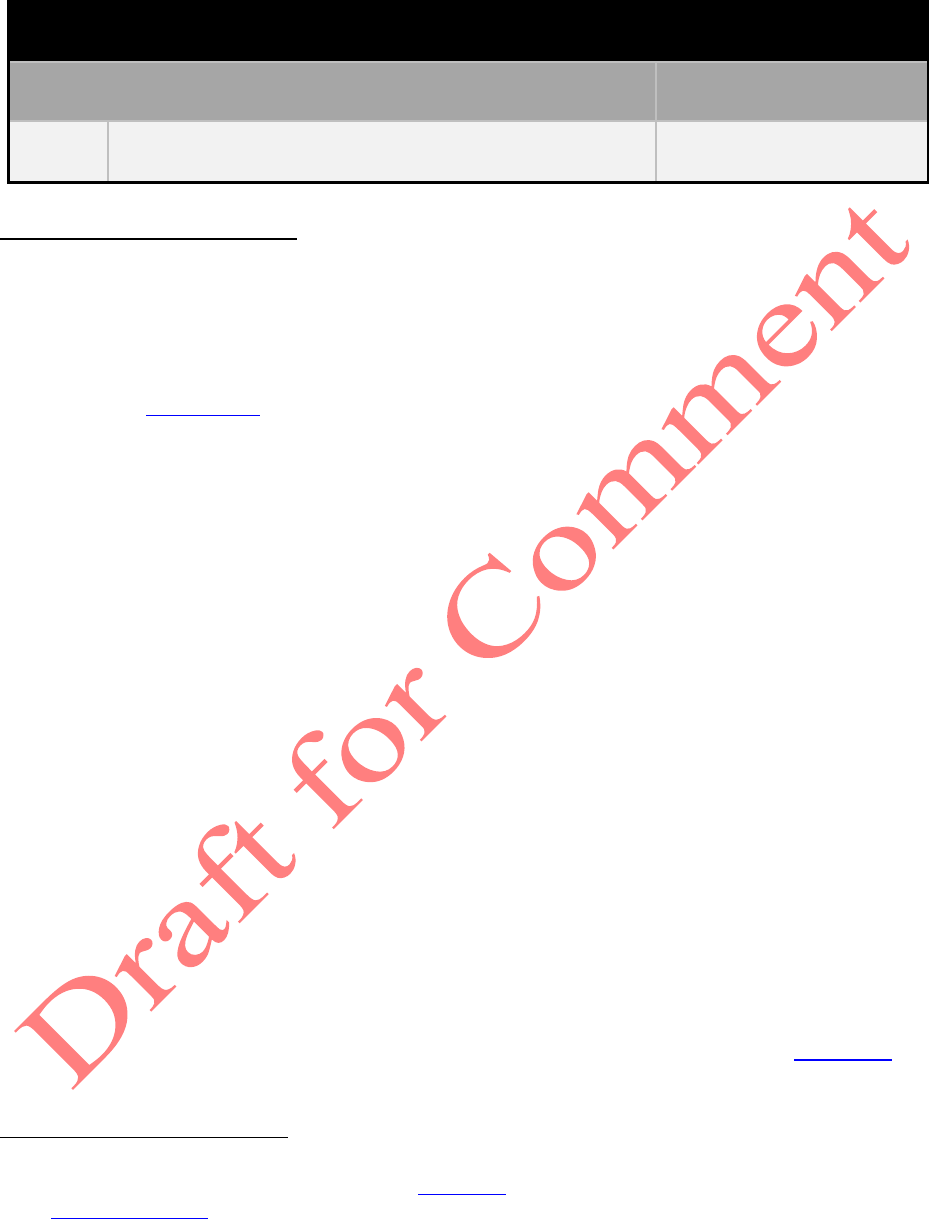

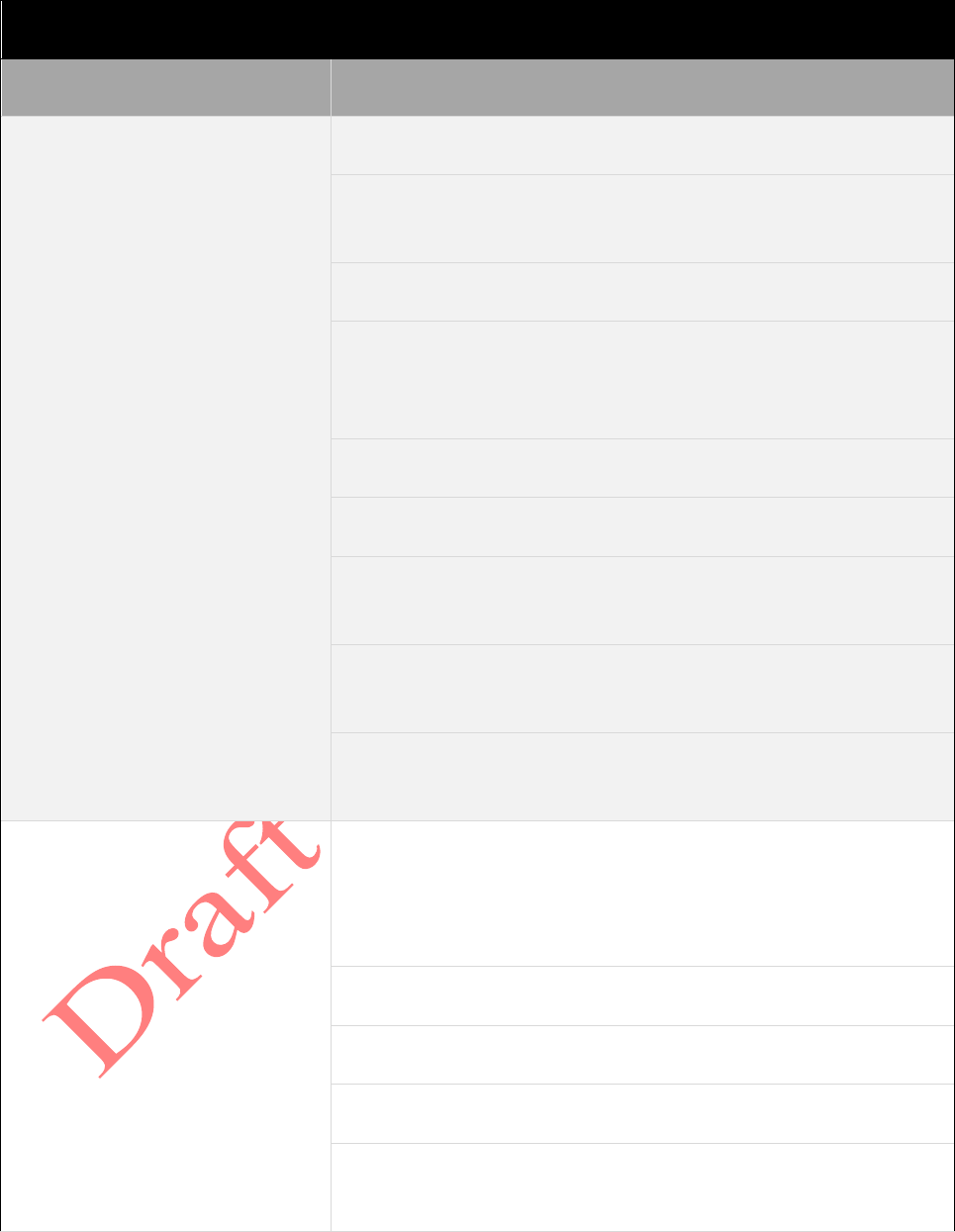

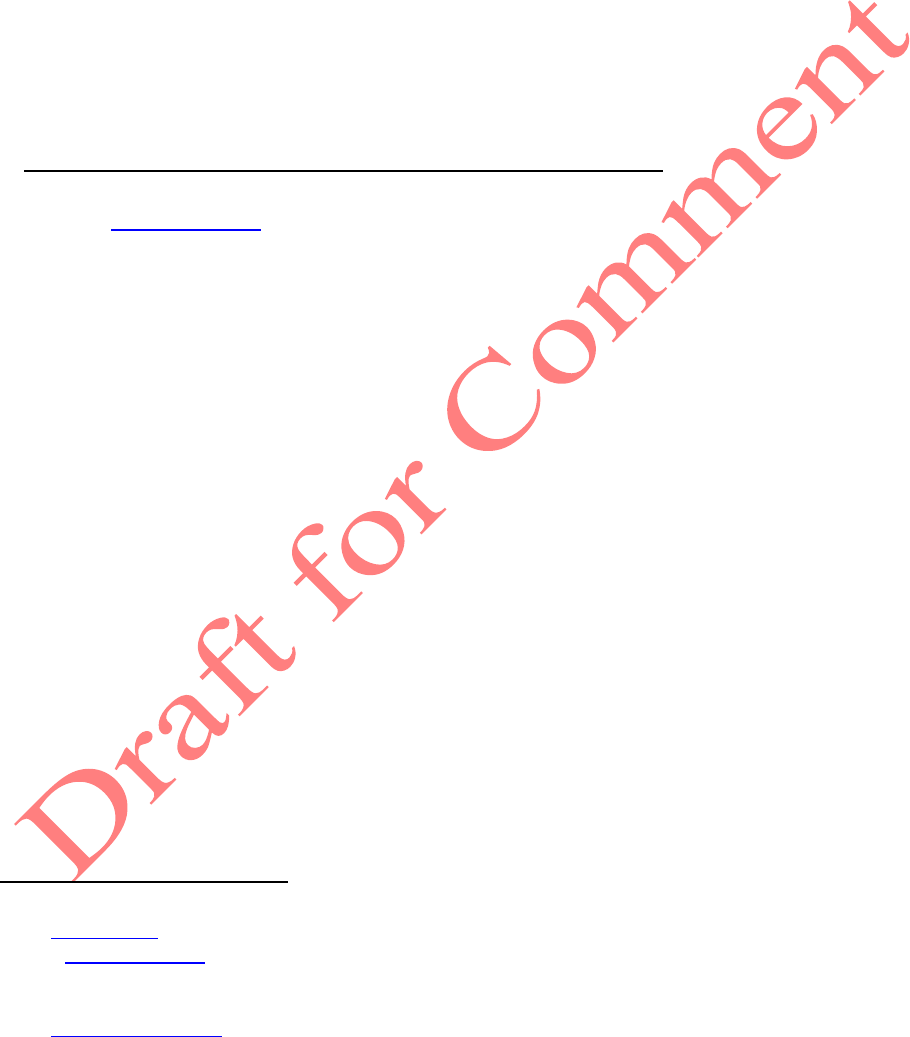

FACTORS AND CONSIDERATIONS FOR EXTREME HARDSHIP

Factors

Considerations

Family Ties and Impact

Presence of qualifying relative’s ties to family members living

in the United States, including age, status, and length of

residence of any children

Responsibility for the care of any family members in the

United States, in particular children and elderly or disabled

adults

Presence or absence of qualifying relative’s ties outside of the

United States, including to family members living abroad and

how close the qualifying relative is to these family members

Nature of relationship between the applicant and the

qualifying relative, including any facts about the particular

relationship that would either aggravate or lessen the

hardship resulting from separation

Qualifying relative’s age

Length of qualifying relative’s residence in the United States

Length of qualifying relative’s prior residence in the country of

relocation, if any

Military service of qualifying relative, where the stresses and

other demands of such service aggravate the hardship

ordinarily resulting from family separation

Impact on the cognitive, social, or emotional well-being of a

qualifying relative who is left to replace the applicant as

caregiver for someone else, or impact on the qualifying

relative (for example, child or parent) for whom such care is

required

Social and Cultural Impact

Loss of access to the U.S. courts and the criminal justice

system, including the loss of opportunity to request criminal

investigations or prosecutions, initiate family law proceedings,

or obtain court orders regarding protection, child support,

maintenance, child custody, or visitation

Draft USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 9: Waivers

15

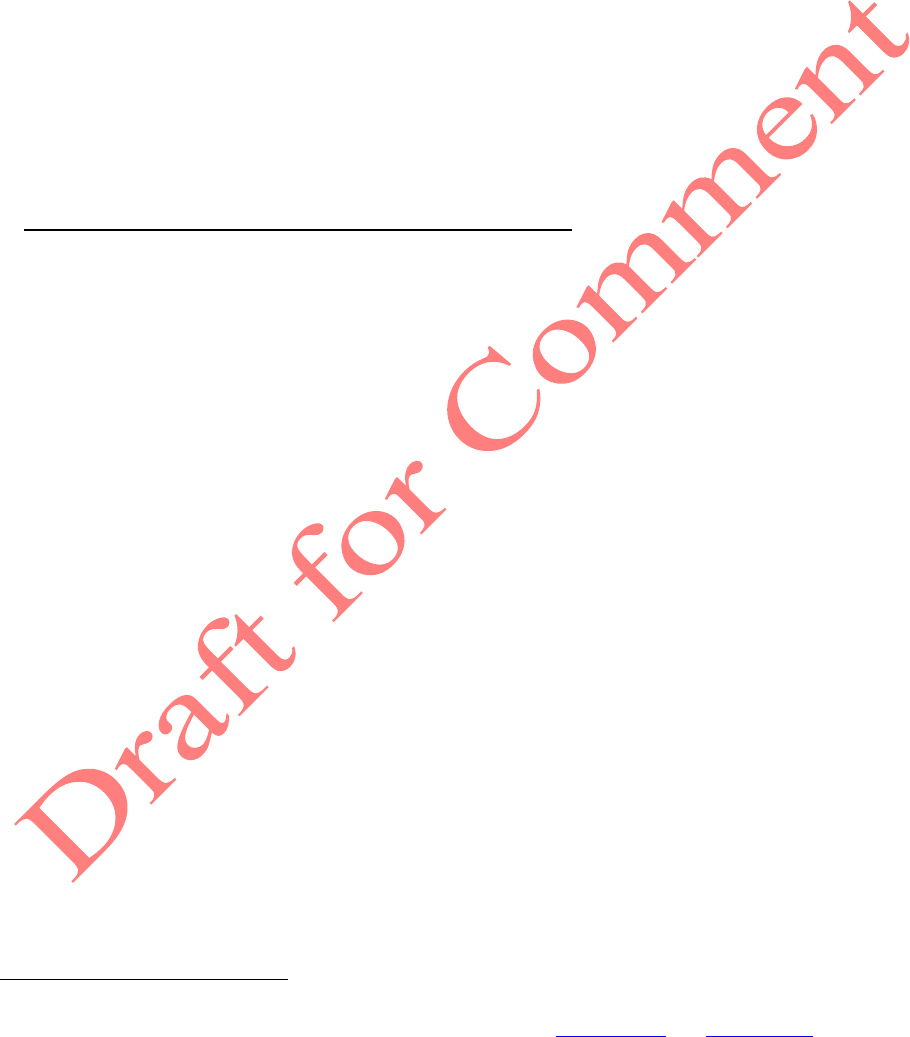

FACTORS AND CONSIDERATIONS FOR EXTREME HARDSHIP

Factors

Considerations

Fear of persecution

Existence of laws and social practices in home country that

punish the qualifying relative because he or she has been in

the United States or is perceived to have Western values

Access or lack of access to social institutions and structures

(official and unofficial) for support, guidance, or protection

Social ostracism or stigma based on characteristics such as

gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, race,

national origin, ethnicity, citizenship, age, political opinion, or

disability

Qualifying relative’s community ties in the United States and

in the country of relocation

Extent to which the qualifying relative has assimilated to U.S.

culture, including language, skills, and acculturation

Difficulty and expense of travel/communication to maintain

ties between qualifying relative and applicant, if the qualifying

relative does not relocate

Qualifying relative’s present inability to communicate in the

language of the country of relocation, taking into account the

time and difficulty that learning that language would entail

Availability and quality of educational opportunities for

qualifying relative (and children, if any) in country of

relocation

Economic Impact

Financial impact of applicant’s departure on the qualifying

relative(s), including the applicant’s or the qualifying relative’s

ability to obtain employment in the country to which the

applicant would be returned and how that would impact the

qualifying relative

Qualifying relative’s need to be educated in a foreign

language or culture

Economic and financial loss due to the sale of a home or

business

Economic and financial loss due to termination of a

professional practice

Decline in the standard of living, including high levels of

unemployment, underemployment, and lack of economic

opportunity in country of nationality

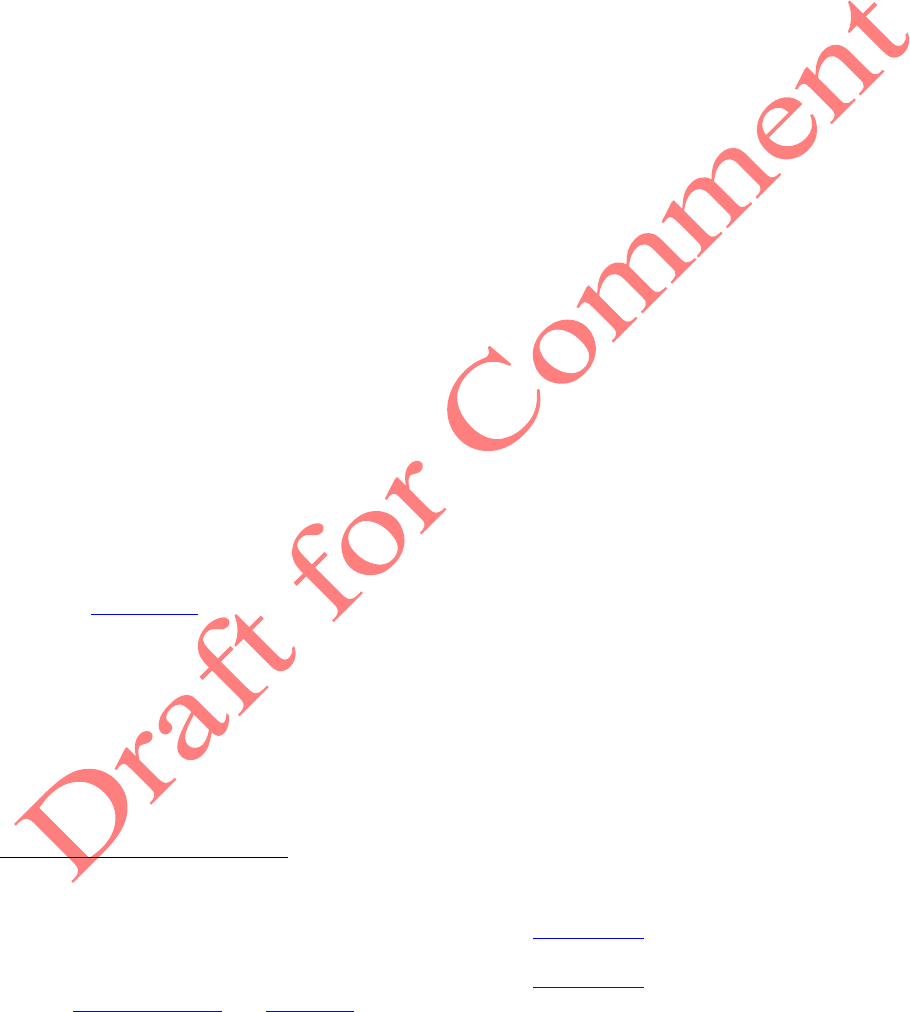

Draft USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 9: Waivers

16

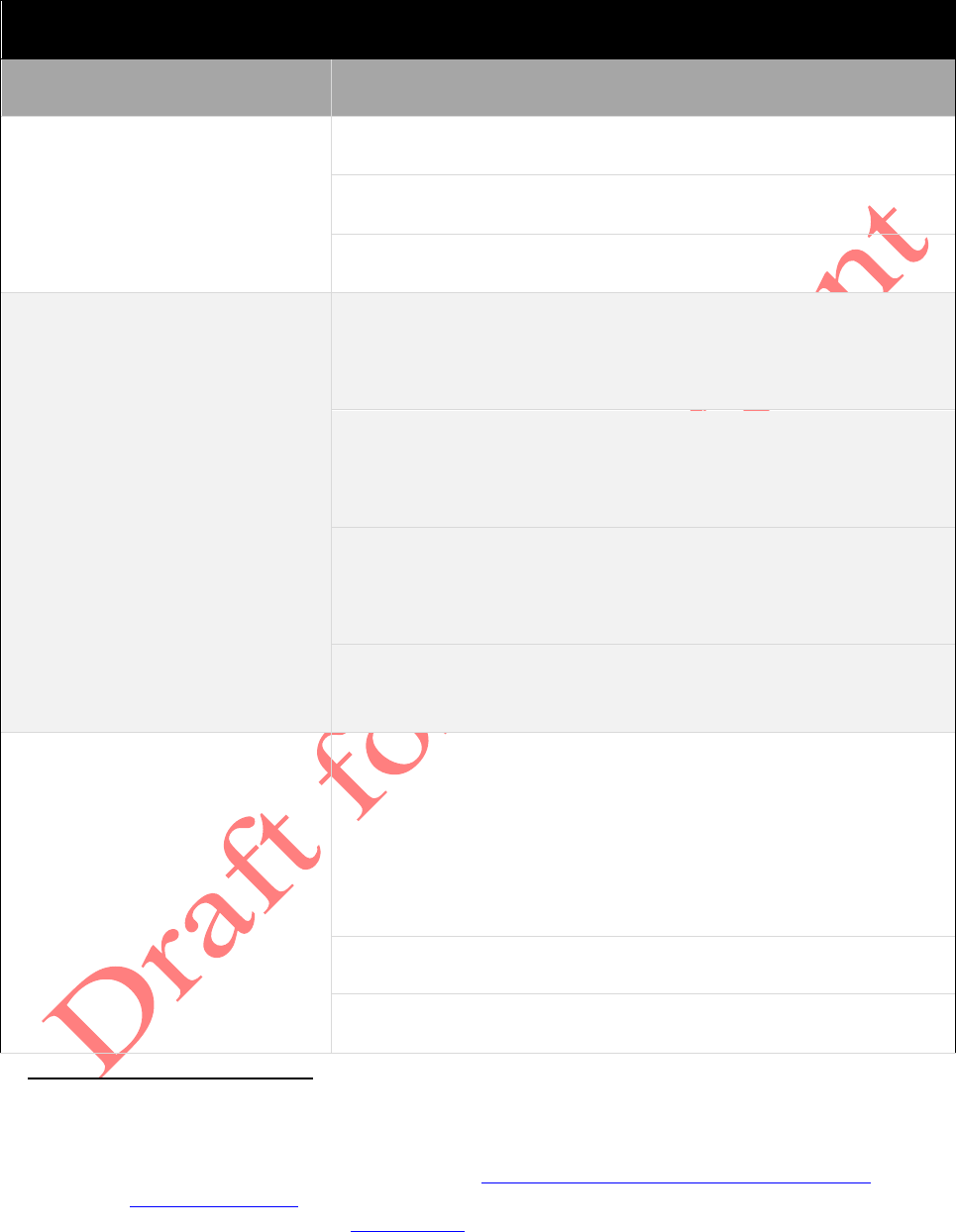

FACTORS AND CONSIDERATIONS FOR EXTREME HARDSHIP

Factors

Considerations

Ability to recoup losses

Cost of extraordinary needs such as special education or

training for children

Cost of care for family members, including children and

elderly, sick, or disabled parents

Health Conditions

& Care

Significant health conditions and impact on the qualifying

relative, particularly when tied to unavailability of suitable

medical care in the country or countries to which the

applicant might relocate

Health conditions of the applicant’s qualifying relative and the

availability and quality of any required medical treatment in

the country to which the applicant would be returned,

including length and cost of treatment

Psychological impact on the qualifying relative due to either

separation from the applicant or departure from the United

States, including separation from other family members living

in the United States

Psychological impact on the qualifying relative due to the

suffering of the applicant, taking into account the nature of

the relationship and any other relevant factors

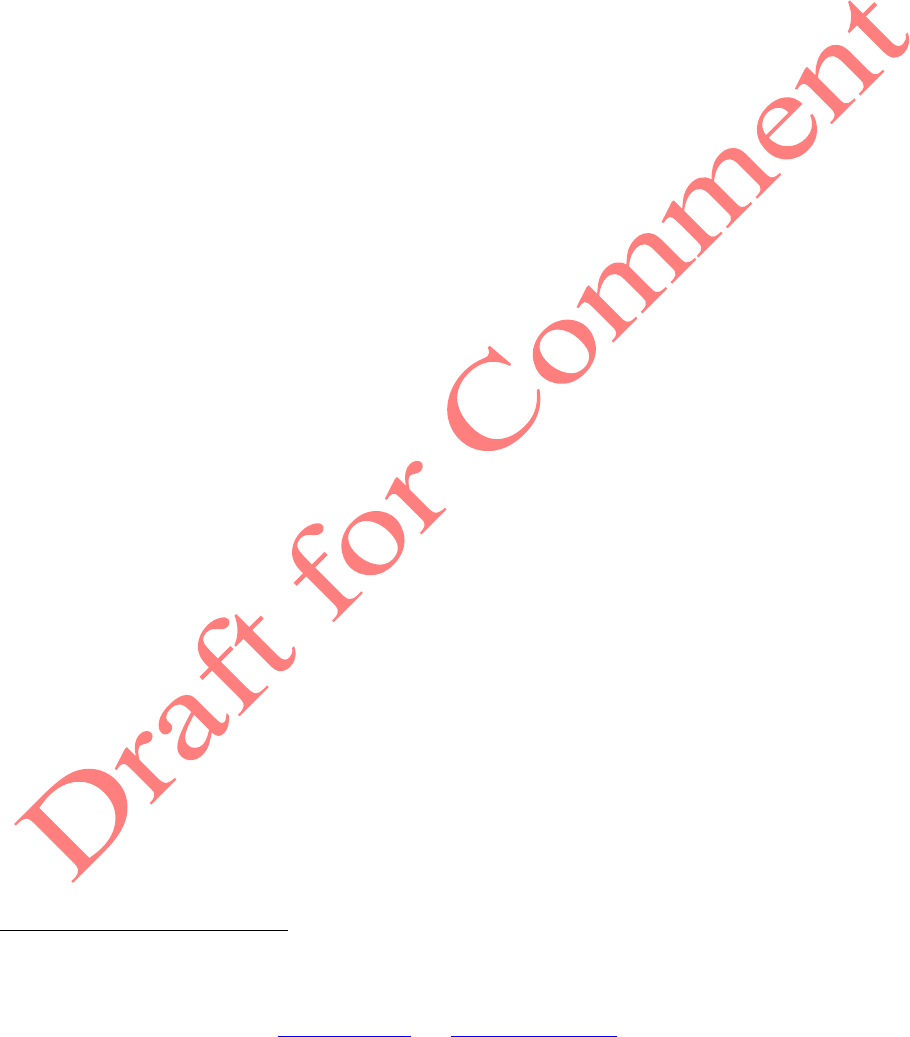

Country Conditions

45

Conditions in the country or countries to which the applicant

would relocate, including civil unrest or generalized levels of

violence, ability of country to address crime/high rates of

murder/other violent crime, environmental catastrophes like

flooding or earthquakes, and other socio-economic or political

conditions that jeopardize safe repatriation or lead to

reasonable fear of physical harm

Temporary Protected Status (TPS) designation

46

Danger Pay for U.S. citizens stationed in the country of

nationality

47

45

The officer should consider any submitted government or nongovernmental reports on country conditions

specified in the hardship claim. In the absence of any evidence submitted on country conditions, the officer may

refer to DOS information on country conditions, such as DOS Country Reports on Human Rights Practices and the

most recent DOS Travel Warnings, to corroborate the claim.

46

For more information on TPS, see the USCIS website.

Draft USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 9: Waivers

17

FACTORS AND CONSIDERATIONS FOR EXTREME HARDSHIP

Factors

Considerations

Withdrawal of Peace Corps from the country of nationality for

security reasons

DOS Travel Warnings issued for the country of nationality

D. Special Circumstances that Strongly Suggest Extreme Hardship

The preceding list identifies factors that bear generally on whether a refusal of admission would

result in extreme hardship to one or more qualifying relatives. USCIS has also determined that

the circumstances below would often weigh heavily in favor of finding extreme hardship. These

sorts of special circumstances are beyond the qualifying relative’s control and ordinarily cause

suffering or harm greater than the common consequences of separation or relocation. An

applicant who is relying on one or more of these special circumstances must submit sufficient

evidence that such circumstances exist. As always, even when these or other special

circumstances are present, the ultimate determination of extreme hardship is based on the

totality of the circumstances in the individual case.

It must be emphasized that the special circumstances listed below are singled out only because

they are especially likely to result in findings of extreme hardship. Many other hardships will

also be extreme, even if they are very different from, or less severe than, those listed below.

48

Further, even the factors discussed are not exclusive; they are merely examples of factors that

can support findings of extreme hardship, depending on the totality of the evidence in the

particular case. Other factors not not discussed could support a finding of extreme hardship,

under a totality of the circumstances.

Eligibility for an immigration benefit ordinarily must exist at the time of filing and at the time of

adjudication.

49

Given the underlying purpose of considering special circumstances, a special

circumstance does not need to exist at the time of filing the waiver request. As long as the

qualifying relative was related to the applicant at the time of filing, a special circumstance

arising after the filing of the waiver request also would often weigh heavily in favor of finding

extreme hardship.

47

See 5 U.S.C. 5928. See the Danger Pay Regulations implemented by the Department of State in its Standardized

Regulations (DSSR).

48

See Section C, Examples of Factors that Might Support Finding of Extreme Hardship [9 USCIS-PM B.4(C)].

49

8 CFR 103.2(b)(1).

Draft USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 9: Waivers

18

1. Qualifying Relative Previously Granted Asylum or Refugee Status

If a qualifying relative was previously granted asylum or refugee status in the United States

from the country of relocation and the qualifying relative’s status has not been revoked, those

factors would often weigh heavily in favor of a finding that relocation would result in extreme

hardship.

As the family member of a foreign national who has been granted asylum or refugee status, the

applicant might also face dangers similar to those that gave rise to the qualifying relative’s

grant of asylum or refugee status. In such a case, the qualifying relative could suffer

psychological trauma in knowing the potential for harm if the applicant returns to the country

of nationality, particularly if the qualifying relative fears returning to that country even to visit

the applicant, and could thereby suffer extreme hardship.

2. Qualifying Relative or Related Family Member’s Disability

If the Social Security Administration or other qualified U.S. Government agency made a formal

disability determination for the qualifying relative, the qualifying relative’s spouse, or a member

of the qualifying relative’s household for whom the qualifying relative is legally responsible,

50

that factor would often weigh heavily in favor of a finding that relocation would result in

extreme hardship.

Absent a formal disability determination, an applicant may provide other evidence that a

qualifying relative or related family member suffers from a medical or physical condition that

makes either travel to, or residence in, the relocation country detrimental to the qualifying

relative or family member’s health or safety.

In cases where the qualifying relative or related family member requires the applicant’s

assistance for care because of the medical or physical condition, that factor would often weigh

heavily in favor of a finding that separation would result in extreme hardship to the qualifying

relative.

3. Qualifying Relative’s Active Duty Military Service

50

The law defines disability as the inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity (SGA) by reason of any

medically determinable physical or mental impairment(s) which can be expected to result in death or which has

lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months. A child under age 18 will be

considered disabled if he or she has a medically determinable physical or mental impairment or combination of

impairments that causes marked and severe functional limitations, and that can be expected to cause death or

that has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months. For more on Social

Security Disability Determinations, see the Social Security Administration website.

Draft USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 9: Waivers

19

If the qualifying relative (who might be a spouse or other qualifying relative) is on active duty

with any branch of the U.S. Armed Forces,

51

relocation will generally be unrealistic, because the

qualifying relative ordinarily will not be at liberty to relocate.

52

If the applicant and the

qualifying relative have been living together – for example, on a military base that

accommodates families or in a private facility off base – the removal of the applicant can

therefore create separation. Under those circumstances, the qualifying relative might well

suffer psychological and emotional harm associated with the separation. The resulting

impairment of his or her ability to serve the U.S. military could exacerbate that hardship. In

addition, even if the qualifying relative’s military service already separates him or her from the

applicant, the applicant’s removal overseas might magnify the stress of military service to a

level that would constitute extreme hardship.

4. DOS Warnings Against Travel to or Residence in Certain Countries

DOS issues travel warnings to notify travelers of the risks of traveling to a foreign country.

53

Reasons for issuing a travel warning include, but are not limited to, unstable government, civil

war, ongoing intense crime or violence, or frequent terrorist attacks. Travel warnings remain in

place until the situation changes. In some of these warnings, DOS advises of travel risks to a

specific region or specific regions of a country.

In other travel warnings, DOS does more than merely notify travelers of the risks; it

affirmatively recommends against travel or residence and makes its recommendation country-

wide. These travel warnings might contain language in which:

DOS urges avoiding all travel to the country because of safety and security concerns;

DOS warns against all but essential travel to the country;

DOS advises deferring all non-essential travel to the country; and/or

DOS advises U.S. citizens currently living in the country to depart.

Generally, the fact that a qualifying relative who is likely to relocate would face significantly

increased danger in the country of relocation would often weigh heavily in favor of a finding of

extreme hardship. If the country of relocation is currently subject to a DOS country-wide travel

warning, this fact would tend to weigh heavily in favor of finding that such increased danger

51

See 10 U.S.C. 101. The term “Armed Forces” means the Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard.

52

Since 8 CFR 103.2(b)(1) requires eligibility at the time of filing and at the time of adjudication, this special

consideration assumes that the qualifying relative was on active duty at the time of filing and continues to be on

active duty at the time of adjudication. See Matter of Alarcon, 20 I&N Dec. 557 (BIA 1992).

53

See DOS Travel Warnings.

Draft USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 9: Waivers

20

exists and, therefore, that relocation would result in extreme hardship. If the travel warning

covers only part of the country of relocation, but the officer finds that that part is one to which

the qualifying relative plans to return despite the increased danger (for example, because of

family relationships or employment opportunities), then that fact would similarly tend to weigh

heavily in favor of finding that relocation would result in extreme hardship. Alternatively, if it is

more likely than not that the qualifying relative would relocate in a part of the country that is

not subject to the travel warning (either because of the danger in the area covered by the

travel warning or for any other reason), the officer should evaluate whether relocation in the

chosen area would itself result in extreme hardship to that qualifying relative.

Conversely, if the applicant were to return to this particular country but the qualifying relative

would be more likely than not to remain in the United States, the separation might well result

in psychological trauma for the qualifying relative.

5. Substantial Displacement of Care of Applicant’s Children

USCIS recognizes the importance of family unity and the ability of parents and other caregivers

to provide for the well-being of children. Moreover, depending on the particular facts, either

the need to assume someone else’s caregiving duties or the continuation of one’s existing

caregiving duties under new and difficult circumstances can be sufficiently burdensome to rise

to the level of extreme hardship for the caregiver. The children do not need to be U.S. citizens

or lawful permanent residents for that to be the case.

54

At least two different scenarios can occur. In one scenario, the primary or sole breadwinner is

refused admission, and the caregiver, who is a qualifying relative, remains behind to continue

the caregiving. The fact that the breadwinner’s refusal of admission would cause economic loss

to the caregiver is not by itself sufficient for extreme hardship. Economic loss is a common

consequence of a refusal of admission. But, depending on the facts of the particular case,

economic loss can create other burdens that in turn are severe enough to amount to extreme

hardship. For example, if the qualifying relative must now take on the combined burdens of

breadwinner and ensuring continuing care of the children, and that dual responsibility would

threaten the qualifying relative’s ability to meet his or her own basic subsistence needs or those

of the person(s) for whom the care is being provided, that dual burden would tend to weigh

heavily in favor of finding extreme hardship. In addition, depending on the particular

circumstances, the qualifying relative may suffer significant emotional and psychological

impacts from being the sole caregiver of the child(ren) that exceed the common consequences

of being left as a sole parent.

54

In this scenario, the children are assumed to be under age 21. See INA 101(b)(1) and INA 101(c)(1).

Draft USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 9: Waivers

21

If the refusal of admission would result in a substantial shift of caregiving responsibility from

the applicant to a qualifying relative, and that shift would disrupt family, social, and cultural

ties, or hinder the child(ren)’s psychological, cognitive, or emotional development, or otherwise

frustrate or complicate the qualifying relative’s efforts to provide a healthy, stable, and caring

environment for the child(ren), the additional psychological and economic stress for the

qualifying relative could exceed the levels of hardship that ordinarily result from family

separation – depending, again, on the totality of the evidence presented. If that is found to be

the case, such a consequence would tend to weigh heavily in favor of a finding of extreme

hardship to the qualifying relative, provided the applicant shows:

The existence of a bona fide parental or other caregiving relationship between the

applicant and the child(ren);

The existence of a bona fide relationship between the qualifying relative and the

child(ren); and

The qualifying relative would become the primary caretaker

55

for the child(ren) or

otherwise would take on significant parental or other caregiving responsibilities.

To prove a bona fide relationship to the child(ren), the applicant and qualifying relative should

have emotional and/or financial ties or a genuine concern and interest for the child(ren)’s

support, instruction, and general welfare.

56

Evidence that can establish such a relationship

includes:

Income tax returns;

Medical or insurance records;

School records;

Correspondence between the parties; or

Affidavits of friends, neighbors, school officials, or other associates knowledgeable

about the relationship.

To prove the qualifying relative either would become the primary caretaker for the child(ren) or

would otherwise take on significant parental or other caregiving responsibilities, the qualifying

55

A primary caretaker is someone who addresses most of the children’s basic needs.

56

USCIS applies a similar principle when assessing whether there is a bona fide relationship between a father and

his child born out of wedlock. See INA 101(b)(1)(D) and 8 CFR 204.2(d)(2)(iii).

Draft USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 9: Waivers

22

relative needs to show an intent to assume those responsibilities. Evidence of such an intent

could include:

Legal custody or guardianship of the child, such as a court order;

Other legal obligation to take over parental responsibilities;

Affidavit signed by qualifying relative to take over parental or other caregiving

responsibilities; or

Affidavits of friends, neighbors, school officials, or other associates knowledgeable

about the qualifying relative’s relationship with the children or intentions to assume

parental or other caregiving responsibilities.

E. Hypothetical Case Examples

Scenario # 1: AB has lived continuously in the United States since entering without inspection 7

years ago. He and his U.S. citizen wife have been married for 4 years. If AB is refused admission,

it is reasonably foreseeable that his wife would relocate with him. His wife is a sales clerk. A

similar job in the country of relocation would pay far less. In addition, she does not speak the

language of the relocation country, lacks experience in the country, and lacks the ties that

would facilitate social and cultural integration and opportunities for employment. AB himself is

an unskilled laborer who similarly would command a much lower salary in the country of

relocation. The couple has no children.

Analysis: These facts alone generally would not favor a finding of extreme hardship. The

hardships to the qualifying relative, even when aggregated, include only common

consequences of relocation – economic loss and the social and cultural difficulties arising

mainly from her inability to speak the language.

Scenario # 2: The facts are the same as in Scenario # 1 except that now the couple has a 9-year-

old U.S. citizen daughter who would relocate with them if AB is refused admission. The child

was born in the United States and has lived here her entire life. AB’s wife and daughter both

have close relationships with AB’s wife’s U.S. citizen sister and brother-in-law, who are the

child’s aunt and uncle, and this couple’s U.S. citizen children, who are the child’s cousins, as

well as other members of the family. They all live in close proximity with one another, have

close emotional bonds, and visit each other frequently, and the aunt and uncle help care for the

child. Neither AB’s wife’s family nor (for this particular waiver) the child are qualifying relatives,

but AB’s wife, who is a qualifying relative, would suffer significant emotional hardship from

seeing the suffering of both her young child and her sister’s family (the child’s aunt, uncle and

cousins), all separated from one another, as well as separated from other family members, and

from losing the emotional bonds she and her child have with her sister’s family and other family

members, and financial benefit she receives from the care that her sister and brother-in-law

Draft USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 9: Waivers

23

provide. In addition, the child (like her mother) does not speak the language of the relocation

country.

Analysis: Depending on the totality of the evidence, these additional facts would generally

support a finding of extreme hardship. The aggregate hardships to the U.S. citizen wife now

include not only the economic losses, diminution of professional opportunities, and social,

cultural, and linguistic difficulties – all common consequences – but also the extra emotional

hardship she would experience as a result of seeing the suffering of her young child and also

her sister and the sister’s family, and other members of the family because of the additional

separation, the child’s inability to speak the language, as well as loss of emotional bonds

between all these family members and financial benefit from their contribution to the care of

the child. That is the case even though neither the child nor the aunt, uncle and cousins, or

family members are qualifying relatives for the particular waiver, because their suffering will in

turn cause significant emotional suffering for the U.S. citizen wife, who is a qualifying relative.

Note that even though the common consequences are not alone sufficient to constitute

extreme hardship, they must be added to the other hardships to determine whether the

totality adds up to extreme hardship.

Scenario # 3: Again the facts are the same as in Scenario # 1, except this time AB himself has

LPR parents who live in the United States and who would suffer significant emotional hardship

as a result of separation from their son and their daughter-in-law, with whom they have close

family relationships.

Analysis: Depending on the totality of the evidence, the addition of these facts would generally

favor a finding of extreme hardship. There are now 3 qualifying relatives – AB’s wife and both

his parents. Although the aggregated hardships to AB’s wife alone (under Scenario # 1) include

only the common consequences of a refusal of admission, further aggregating them with the

emotional hardships suffered by the two LPR parents would generally tip the balance in favor of

a finding of extreme hardship, depending, again, on the totality of the evidence.

Scenario # 4: CD has lived continuously in the United States since entering without inspection 4

years ago. She has been married to her U.S. citizen husband for 2 years. It is reasonably

foreseeable that he would choose to remain in the United States in the event she is refused

admission. He has a moderate income, and she works as a housecleaner for low wages. Upon

separating they would suffer substantial economic detriment; in addition to the loss of her

income, he is committed to sending her remittances once she leaves, in whatever amounts he

can afford. They have no children, and there are no extended family members in the United

States.

Analysis: These facts alone generally would not favor a finding of extreme hardship. The

qualifying relative, and the hardships to him, even when aggregated, include only common

consequences – separation from his spouse and economic loss.

Draft USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 9: Waivers

24

Scenario # 5: EF and GH, a married couple from Taiwan, entered the United States on student

visas 19 and 17 years ago, respectively. They overstayed their visas and have lived here ever

since. They have five U.S. citizen children, all of whom were born in the United States and have

lived here their entire lives. In the event that the parents are removed to Taiwan, it is

reasonably foreseeably that the children would relocate with them. The children range in age

from 6 to 15 and are fully integrated into the American lifestyle. None of the children are fluent

in Chinese, and they would have to attend Chinese language public schools if they relocate

because the family would not be able to afford private school. The 15-year-old child in

particular would experience significant disruption to her education in light of her current age

and her inability to speak or understand Chinese. The family of seven would be able to afford

only a one-bedroom apartment upon relocation.

Analysis: This is the fact situation of Matter of Kao, 23 I. & N. Dec. 45 (BIA en banc 2001). The

Board in that case, sitting en banc, held that these facts constitute extreme hardship for the 15-

year-old daughter, who was one of the qualifying relatives. The Board therefore did not need to

decide whether the other qualifying individuals would also suffer extreme hardship upon

relocation. A key factor in that decision was the daughter’s age. In addition to the common

consequences (integration into the American lifestyle, current inability to speak the language of

the country of relocation, lesser educational opportunities, and economic loss), the Board

found that because of her age and the time it would take to become fluent in the language of

the country of relocation, the daughter’s education would be significantly disrupted and she

would experience extreme hardship as a result.

Scenario # 6: KL has lived continuously in the United States since entering without inspection six

years ago. She married a U.S. citizen four years ago and seeks a waiver of the 10-year

inadmissibility bar for unlawful presence based on extreme hardship to her husband. If she is

refused, she would be removed to a country for which the U.S. State Department has issued

travel warnings for specific regions, including the region where her family lives. It is reasonably

foreseeable that her husband would relocate with her, and that because of the danger they

would relocate in one of the areas for which no travel warnings have been issued.

Unemployment throughout the country is extremely high, however, and without the family

connections that they would forfeit by living outside the region of their family’s residence, the

job prospects for both spouses are dim and their basic subsistence needs would be threatened.

Analysis: The fact that parts of the country of relocation are dangerous does not, by itself,

constitute extreme hardship. Similarly, economic loss alone is not extreme hardship. But

economic detriment that is severe enough to threaten a person’s basic subsistence can rise to

the level of extreme hardship. Therefore, if the dangers in parts of the relocation country would

induce the qualifying relative to relocate in other parts of the country where economic

subsistence would be threatened (or if relocation in such parts is reasonably foreseeable for

any other reason), the resulting economic distress would generally favor a finding of extreme

hardship, depending on the totality of the evidence. Conversely, if it were reasonably

foreseeable that because of the economic realities the qualifying relative, despite the danger,

Draft USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 9: Waivers

25

would relocate in a region for which travel warnings have been issued, then that danger would

weigh heavily in favor of finding extreme hardship.

Chapter 5. Extreme Hardship Determinations

A. Evidence

Most instructions that accompany USCIS forms list the types of supporting evidence that an

applicant may submit.

57

The instructions to these forms list some of the relevant extreme

hardship factors and some possible types of supporting evidence. USCIS accepts any form of

probative evidence, including, but not limited to:

Expert opinions;

Medical or mental health documentation and evaluations by licensed professionals;

Official documents, such as birth certificates, marriage certificates, adoption papers, or

other court documents, such as paternity orders or orders of child support;

Photographs;

Evidence of employment or business ties, such as payroll records or tax statements;

Bank records and other financial records;

Membership records in community organizations, confirmation of volunteer activities,

or cultural affiliations;

Newspaper articles and reports;

Country reports from official and private organizations;

Personal oral testimony;

58

and

Affidavits (including statements that are not notarized but are signed “under penalty of

perjury” as permitted by 28 U.S.C. 1746) or letters from the applicant or any other

57

A waiver that requires a showing of extreme hardship to a qualifying relative is currently submitted on an

Application for Waiver of Grounds of Inadmissibility (Form I-601) or an Application for Provisional Unlawful

Presence Waiver (Form I-601A).

58

An officer who relies on personal oral testimony must note in the record that the person was placed under oath.

The officer should also take notes or record the testimony.

Draft USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 9: Waivers

26

person.

If the applicant indicates that certain relevant evidence is not available, the applicant must

provide a reasonable explanation and possible documentation that explains why the evidence is

unavailable.

59

Depending on the country where the applicant is from, is being removed to, or

resides, certain evidence may be unavailable. If the applicant alleges that documentary

evidence such as a birth certificate is unavailable, the officer may consult the DOS Foreign

Affairs Manual,

60

when appropriate, to verify whether these particular documents are

ordinarily unavailable in the applicant’s country.

B. Burden of Proof and Standard of Proof

The applicant bears the burden of proving that the qualifying relative would suffer extreme

hardship. He or she must establish eligibility for a waiver by a preponderance of the evidence.

61

If the applicant submits relevant, probative, and credible evidence that leads the officer to

believe that reasonably foreseeable relocation or reasonably foreseeable separation would

“more likely than not” result in extreme hardship to a qualifying relative, the applicant has

satisfied the preponderance of the evidence standard of proof.

62

To determine whether either relocation or separation is reasonably foreseeable, the officer

should consider all the evidence presented. A mere assertion or possibility does not make

relocation or separation (as the case may be) reasonably foreseeable. That evidence includes

the applicant’s explanation as to why a refusal of admission would result in extreme hardship to

a qualifying relative.

63

The applicant’s statement alone, made under penalty of perjury, will

ordinarily suffice to establish that either relocation or separation (as the case may be) is

reasonably foreseeable. An officer who nonetheless has reason to doubt that relocation or

separation (as the case may be) is in fact reasonably foreseeable may issue an RFE requesting

supporting evidence. Such evidence might include, for example, an affidavit from the applicant

or an affidavit from an adult qualifying relative. If the record contains evidence of the qualifying

relative’s subjective intent to relocate or separate (as the case may be), such evidence is

relevant to whether relocation or separation is reasonably foreseeable.

59

See 8 CFR 103.2(b).

60

See the DOS website.

61

See Matter of Chawathe, 25 I&N Dec. 369 (AAO 2010) (identifying preponderance of the evidence as the

standard for immigration benefits generally, in that case naturalization).

62

See Matter of Chawathe, 25 I&N Dec. 369, 376 (AAO 2010) (preponderance of the evidence means more likely

than not). See Fisher v. Vassar College, 114 F.3d 1332, 1333-34 (2nd Cir. 1997) (holding that in other contexts

“preponderance of the evidence” means more likely than not).

63

Required by both Form I-601, Application for Waiver of Grounds of Inadmissibility, and Form I-601A, Application

for Provisional Unlawful Presence Waiver.

Draft USCIS Policy Manual, Volume 9: Waivers

27

An applicant who claims that the qualifying relative has severe, ongoing medical problems will

not likely be able to establish the existence of these problems without providing medical

records documenting the qualifying relative’s condition. Officers cannot substitute their

medical opinion for a medical professional’s opinion; instead the officer must rely on the

expertise of reputable medical professionals. A credible, detailed statement from a doctor may

be more meaningful in establishing a claim than dozens of test results that are difficult for the

officer to decipher. However, nothing in this situation changes the requirement that all

evidence sumitted by applicants should be considered to evaluate the totality of the

circumstances.

Similarly, if the applicant claims that the qualifying relative will experience severe financial

difficulties, the applicant will not likely be able to establish these difficulties without submitting

financial documentation. This could include, but is not limited to, bank account statements,

employment and income records, tax records, mortgage statements, leases, and proof of any

other financial liabilities or earnings.

If not all of the required initial evidence has been submitted or the officer determines that the

totality of the evidence submitted does not meet the applicable standard of proof, the officer

should issue an RFE unless he or she determines there is no possibility that additional evidence

available to the person might cure the deficiency.

If evidence in the record leads the officer to reasonably believe that undocumented assertions

of the extreme hardship claim are true, the officer may accept the assertion as sufficient to

support the extreme hardship claim. The preponderance of the evidence standard does not

require any specific form of evidence; it requires the applicant to demonstrate only that it is

more likely than not that the refusal of admission will result in extreme hardship to the

qualifying relative(s). Any evidence that satisfies that test will suffice.

64

If the officer finds that the applicant has met the above burden, the officer should proceed to

the discretionary determination.

65

If the officer ultimately finds that the applicant has not met

the above burden, the application must be denied.

Chapter 6. Discretion