The Impact of an Employee’s Psychological Contract

Breach on Compliance with Information Security

Policies: Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation

Daeun Lee

∗1

, Harjinder Singh Lallie

†2

, and Nadine Michaelides

‡3

2

Cyber Security Centre, WMG, University of Warwick, Coventry, CV4 7AL

Abstract

Despite the rapid rise in social engineering attacks, not all employees are as com-

pliant with information security policies (ISPs) to the extent that organisations expect

them to be. ISP non-compliance is caused by a variety of psychological motivation.

This study investigates the effect of psychological contract breach (PCB) of employees

on ISP compliance intention (ICI) by dividing them into intrinsic and extrinsic moti-

vation using the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) and the general deterrence theory

(GDT). Data analysis from UK employees (n=206 ) showed that the higher the PCB,

the lower the ICI. The study also found that PCBs significantly reduced intrinsic mo-

tivation (attitude and perceived fairness) for ICI, whereas PCBs did not moderate the

relationship between extrinsic motivation (sanction severity and sanctions certainty)

and ICI. As a result, this study successfully addresses the risks of PCBs in the field of

IS security and proposes effective solutions for employees with high PCBs.

Keywords: psychological contract; psychological contract breach; cybersecurity behaviour;

information system security; information security policies

Competing interests. The authors declare that we have no competing financial or non-

financial interests that are directly or indirectly related to the work submitted for publication.

1 Introduction

Organisational information security breaches can largely be explained by human error and

omission (ISF, 2020). In other words, if employees deliberately or unintentionally fail to keep

the information safe, it is insufficient to take technical countermeasures for the protection

∗

Daeun.Lee@warwick.ac.uk

†

HL@warwick.ac.uk

‡

Nadine.Michaelides@warwick.ac.uk

1

arXiv:2307.02916v1 [cs.CY] 6 Jul 2023

of the information. Accordingly, various psychological factors motivating employees’ failure

to comply with ISP compliance have been raised in the cyber security literature. Among

them, the Psychological Contract (PC) was presented as one of the significant human factors

provoking employees’ cybersecurity behaviours (Ertan et al., 2018; Leach, 2003). The PC is

a set of beliefs about reciprocal obligations between an employee and an employer (Robin-

son and Wolfe Morrison, 2000). According to the existing research, psychological contract

breaches (PCBs) provoke poor organisational citizenship behaviours (Mai et al., 2016a) and

even poor work performance (Bal et al., 2013). These results imply that employees’ PCBs

are likely to reduce their ISP compliance intentions. However, empirical studies concerning

the direct correlation between PCB and ISP compliance intentions have not been sufficiently

conducted to date.

This research aims to evaluate the impact of PCB, a new potential psychological factor,

on deficient ISP compliance intentions. The research also measures the impact of PCB on in-

trinsic and extrinsic motivation towards ISP compliance intentions in order to multifacetedly

examine the risks of PCB. Consequently, the study can address the important role of PCB

in IS security and provide a set of suggestions for employees having PCBs.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 aims to analyse the existing

literature on PCB and ISP compliance intention to develop research hypotheses. Section

3 presents data analysis and results based on the research framework. The discussion in

Section 4 proceeds to interpret and analyse the results to answer the research questions.

Finally, Section 5 describes the conclusions, recommendations, and limitations of this study.

2 Background

2.1 Psychological Contract

Psychological contract has emerged as one of the most crucial factors in workforce manage-

ment. Unlike the documented contract, the psychological contract is the unwritten contract

and refers to an individual’s beliefs about mutual obligations between an employee and an

organisation (Rousseau, 1989). When an employee perceives that the organisation is obliged

to reciprocity for his or her contributions, the psychological contract is created. The contract

has been constituted by paid-for-promises (e.g. high salary, promotion, long-term job secu-

rity, or career development) made in exchange for some either implied or stated consideration

such as hard work, accepting training, or transfers. Thus, psychological contracts are viewed

as unwritten promises not as expectations. This leads employees to feel disappointed when

psychological contracts are breached (Robinson and Rousseau, 1994).

The consequences of psychological contract breaches have been found to negatively impact

perceived obligations towards an employer, citizenship behaviour, commitment, satisfaction,

intentions to remain and even work performance (Robinson, 1996; Robinson and Rousseau,

1994; Robinson et al., 1994). For example, employees who experienced PCB do not tend

to contribute to their organisation since they have no expectation of future benefit, which

is the organisation’s obligation. Moreover, extreme cases of psychological contract breach

could result in retaliation, sabotage, identity theft, and aggressive behaviour (Morrison and

Robinson, 1997). Recent empirical studies have found PCB to negatively impact organisa-

2

tional behaviour (AL-Abrrow et al., 2019; Mai et al., 2016b), job satisfaction, commitment

and intention to leave (Trybou and Gemmel, 2016), user resistance for the information sys-

tem implementation (Lin et al., 2018), trust in organisation (Abela and Debono, 2019), and

productive work behaviour (Ma et al., 2019). PCB could lead to cybercrime conducted as a

result of insider threat brought about by the PCB. However, this has not been thoroughly

investigated.

2.2 The Relationship Between Psychological Contracts and Inten-

tion to comply with Information Security Policies

ISP (Information Security Policy) refers to any document that covers security programs,

system controls and user behaviour within an organisation to realise security objectives

(Landoll, 2017). ISP can be categorised into four levels: organisational-level policies, secu-

rity program-level policies, user-level policies, and system and control-level policies. Among

these, the present study focuses on user-level policies in order to identify an employee’s

psychological factors that influence their behaviour and intentions. According to ISO (In-

ternational Standards Organisation) 27001/2, user-level policies consist of eight elements;

security responsibility agreement, acceptable use of assets, security awareness program, re-

movable media disposal procedures, document control plan, mobile device security policy,

telework security policy, and disciplinary process (Landoll, 2017).

As cybercrime increases and becomes more severe and sophisticated, organisations put

greater effort into information security risk management by implementing security measures

and policies. Nonetheless, not only is the establishment of ISP within the organisation

required, but employees must actively comply with ISP, playing a key role in substantially

protecting cyber threats. Especially these days when social engineering is prevalent, the

importance of encouraging employees to conform to ISP is increasingly emphasised (Flores

and Ekstedt, 2016). Therefore, it is expected that not only the information systems but also

the users are obliged to adhere to the ISP statements.

However, if employees do not understand the importance of ISP compliance and are not

willing to comply with it, all the technical measures and strategies that organisations have

put in place will be in vain (Herath and Rao, 2009b). Hence, human factors affecting ISP

compliance intentions are needed to be understood to encourage their motivation.

The PCB has been proposed as one of the most important factors influencing employees

to perform security behaviours and to comply with security procedures. Leach (2003) stated

that employees are psychologically pressured to act in accordance with the expectations of

the organisation by voluntarily limiting and maintaining their behaviours within the range

of accepted practices. Therefore, if employees feel that the company breached their psycho-

logical contract, they could feel exasperated and compelled to get even with the company.

In addition, Abraham (2011) proposed PCB as one of the most influential factors associ-

ated with psychological ownership, organisational commitment, trust, as well as procedural

justice.

While the necessity of investigating the impact of PCB in IS security has been increased,

relevant empirical studies have not been sufficiently conducted. To the best of our knowledge

there has been only one relevant empirical study: Han et al. (2017a) examined the mediating

3

role of PCF (Psychological Contract Fulfillment) between perceived costs and ISP compli-

ance intentions. The study conducted quantitative research seperated into supervisor and

supervisee groups. As a result, it was found that PCF mitigates the negative impact of

perceived costs on ISP compliance intentions only in the supervisor group. However, in this

study, the perceived cost had no significant influence on ISP compliance intentions in both

supervisor and supervisee groups. Accordingly, the study presents the hypothesis below.

H1: High Psychological Contract Breach has a strong negative effect on ISP compliance

intentions.

2.3 Motivational Factors for ISP compliance intentions

Extensive research has been done to examine human factors which influence employee compli-

ance with ISP. Many behavioural theories (e.g. TPB (Theory of Planned Behaviour), GDT

(General Deterrence Theory), PMT (Protection Motivation Theory), SCT (Social Cognitive

Theory)) in IS literature have addressed motivators affecting ISP compliance. According to

systematic literature reviews on behavioural theories, the most frequently used theory in IS

security, was TPB followed by GDT (Alias et al., 2019; Lebek et al., 2013, 2014).

The TPB suggests that an individual’s behavioural intentions are determined by self-

direction along with efforts to perform a target behaviour, or by motivation in terms of

conscious plan and decision (Conner, 2020). The TPB is mainly composed of attitudes, self-

efficacy, and subjective norms. Attitudes are an individual’s overall assessments of a target

behaviour, and self-efficacy is an individual’s expectation of how well they can control the

target behaviour. Additionally, subjective norm is a function of normative beliefs which are

an individual’s perceptions of the preferences of those around him who believe he should en-

gage in targeted behaviour (Conner, 2020). These three components are the most important

psychological factors in motivating and predicting ISP compliance behaviours and intentions

(Lebek et al., 2014; Nasir et al., 2017).

On the other hand, the GDT explains that a psychological process is made by deterring

criminal behaviour only when people perceive that legal sanctions are clear, expeditious and

harsh (Williams and Hawkins, 1986). The GDT primarily consists of sanction severity and

sanction certainty; sanction severity refers to an individual’s perception that penalties for

non-compliance are severe and sanction certainty indicates an individual’s perception that

risk of delinquent behaviour to be detected is high (Williams and Hawkins, 1986; Safa et al.,

2019).

2.4 Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation

People are motivated both internally and externally to take certain actions. Organisations

typically seek to establish external measures such as sanctions and penalties for deviant

cybersecurity behaviours, rather than increasing employees’ internal motivations. Extrinsic

Motivation is defined as decision-making based on external factors such as a reward, surveil-

lance, and punishment (Benabou and Tirole, 2003) as opposed to Intrinsic Motivation, which

is an inherent desire to undertake the work even without specific rewards (Benabou and Ti-

role, 2003; Makki and Abid, 2017).

4

However, intrinsic and extrinsic motivation sometimes conflict with each other. Ac-

cording to Benabou and Tirole (2003), some researchers insist that extrinsic motivations

such as sanctions and rewards are often counterproductive since they often impede intrinsic

motivation. This is because extrinsic motivations have limited effect on current employee

engagement and reduces motivation to perform the same task later without compensation.

Therefore, many social psychology studies emphasise the necessity to increase employee self-

esteem rather than increase extrinsic motivation (Benabou and Tirole, 2003). Accordingly,

the study compares the effects of PCB on intrinsic and extrinsic motivation for ISP compli-

ance intentions to identify how to motivate people who have experienced PCB to adhere to

ISP.

2.4.1 Intrinsic Motivations

A psychological contract breach is known to induce negative emotional responses, which in

turn reduces intrinsic motivation at work (de Lange et al., 2011; Morrison and Robinson,

1997). Conversely, it has been shown that psychological contract fulfilment increases motiva-

tion towards organisational commitment (Berman and West, 2003). Therefore, the present

study suggests PCB negatively influences intrinsic motivation towards ISP compliance in-

tentions.

The study adopted attitudes and self-efficacy of TPB as intrinsic motivators of ISP

compliance intentions. This is because attitude has been studied as the most significant

intrinsic motivator (Bulgurcu et al., 2011), and intrinsic motivation consists of autonomy

and competence, which are aligned with self-efficacy (Alzahrani et al., 2018).

Additionally, employee psychological contract violations have been found to provoke neg-

ative organisational attitudes (e.g. job satisfaction, effective commitment, turnover inten-

tions) (Pate et al., 2003; Zhao et al., 2007). On the other hand, the correlation between

perceived contract violation and low job satisfaction was found to be weaker as the work-

related self-efficacy increased (De Clercq et al., 2019). Therefore, it is necessary to study the

mitigating role of self-efficacy on the negative effects of PCB.

Employees who have experienced psychological contract breach may think that following

the ISP is important but unfair, which may unwittingly lead to inadequate cybersecurity.

Perceived Fairness can be defined as an individual’s perception of the fairness of an organisa-

tion’s ISP requirements, that exists within the internal context of ISP compliance (Bulgurcu

et al., 2011). Perceived fairness has been found positively affect attitudes towards ISP com-

pliance (Bulgurcu et al., 2009, 2011). In terms of the relationship between perceived fairness

and PCB, some research has found that employees’ beliefs of unfairness in the organisa-

tion’s regulations and treatments can be directly linked to psychological contract violation

(Harrington and Lee, 2015; Morrison and Robinson, 1997). Moreover, psychological contract

fulfilment has been found to raise employees’ perception of performance appraisal fairness

(Harrington and Lee, 2015). It was also found that higher perceived fairness mitigated the

negative influence of PCB on those with violated feelings (Lin et al., 2018). Hence, the

study additionally measures an employee’s perceived fairness towards ISP compliance as an

intrinsic motivational factor. Accordingly, the study proposes the following hypotheses:

H2: Higher intrinsic motivation (Attitudes, Self-efficacy, and Perceived Fairness) has a

stronger positive effect on ISP compliance intentions.

5

H3a: There is a negative effect of Psychological Contract Breach on Attitudes towards

ISP compliance intentions.

H3b There is a negative effect of Psychological Contract Breach on Self-efficacy towards

ISP compliance intentions.

H3c: H3c: There is a negative effect of Psychological Contract Breach on Perceived

Fairness towards ISP compliance intentions.

2.4.2 Extrinsic Motivations

Employees are sometimes compelled to follow organisational policies, even if they are un-

willing to do so, to avoid disadvantages such as penalties and reputational damage. The

study suggested subjective norm of TPB as well as sanction severity and sanction certainty

of GDT as extrinsic motivators to influence employee compliance with ISP. Although some

researchers have regarded subjective norms as somewhat voluntary behaviours, it has been

considered as an extrinsic motivator in IS studies since intrinsic motivations are based on

the employee’s desire to perform the task for himself or herself (Herath and Rao, 2009a).

Therefore, subjective norm, sanction severity, and sanction certainty can be classified as

extrinsic motivation factors in this study.

However, those extrinsic factors motivating employees to adhere to the policies can con-

flict with intrinsic motivation. According to a systematic literature review on IS behaviour

theories, those extrinsic motivators of GDT – sanction severity and sanction certainty – have

been found not to significantly influence IS deviant behaviours compared to TPB (Nasir

et al., 2017; Safa et al., 2019). This implies that the intrinsic motivators including PCB

can either reduce the positive correlation between extrinsic motivation and ISP compliance

intentions or reverse the direction of the positive correlation in a negative way. For instance,

higher extrinsic motivation has a less positive effect or has no distinct effect on ISP compli-

ance intentions when an employee’s PCB is high. Conversely, when an employee’s PCB is

low, higher extrinsic motivation has a higher positive effect on ISP compliance intentions.

Therefore, the study proposes the following hypotheses:

H4: High extrinsic motivation (Subjective norms, Sanction severity, and Sanction cer-

tainty) has a stronger positive effect on and ISP compliance intentions.

H5a: Psychological contract breach moderates the relationship between Subjective Norms

and ISP compliance intentions.

H5b: Psychological contract breach moderates the relationship between Sanction Severity

and ISP compliance intentions.

H5c: Psychological contract breach moderates the relationship between Sanction Cer-

tainty and ISP compliance intentions.

Lastly, since PCB can be classified as intrinsic motivation, it is assumed that PCB has

a greater negative effect on people having intrinsic motivation than those having extrinsic

motivation. Therefore, people who follow ISPs due to the external factors may not be

relatively affected by the PCB since external factors are not changed by PCB. However,

those who intrinsically seek to follow ISPs may be greatly affected by the PCB. Accordingly,

the study suggests the following hypothesis:

H6: The effect of PCB on Intrinsic Motivation is stronger than the moderating effect of

PCB between Extrinsic Motivation and ISP compliance intention.

6

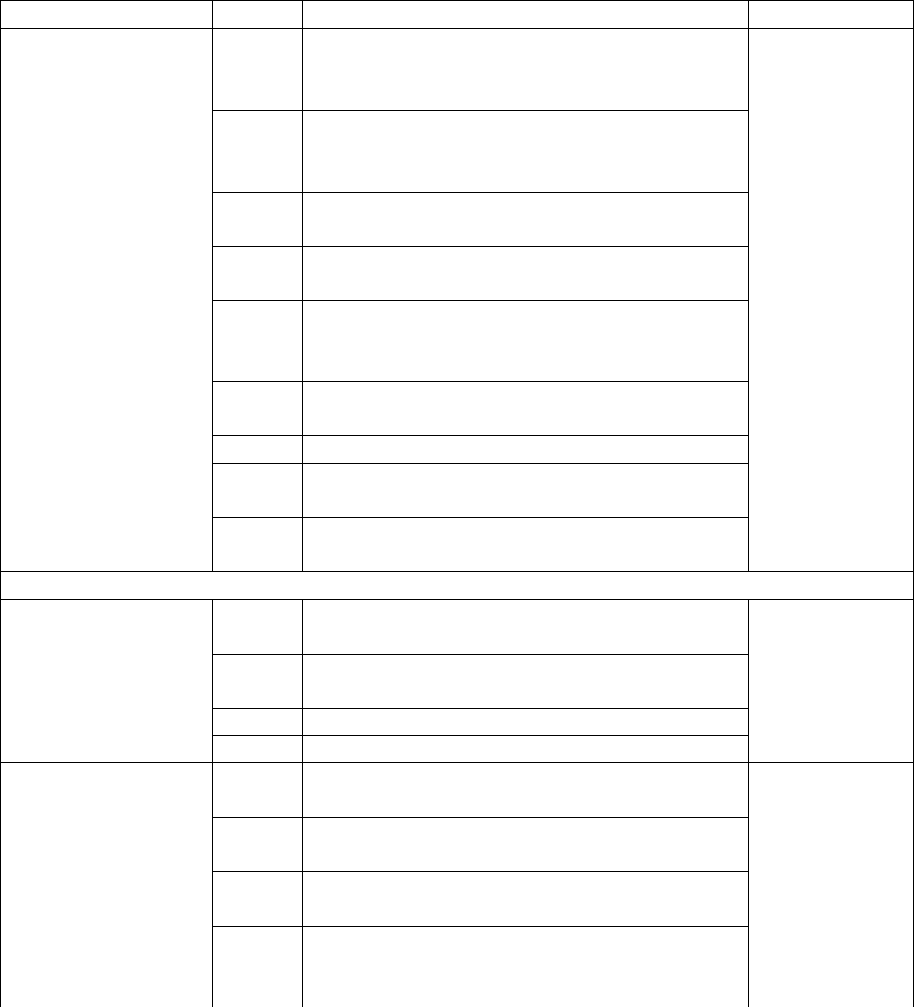

Consequently, the study combines two behaviour theories, TPB and GDT, classifying

into intrinsic and extrinsic motivation based on the main research question, the negative

impact of PCB on ISP compliance intentions. Accordingly, the study can differ the impact

of PCB on intrinsic motivation to extrinsic motivation towards ISP compliance intentions.

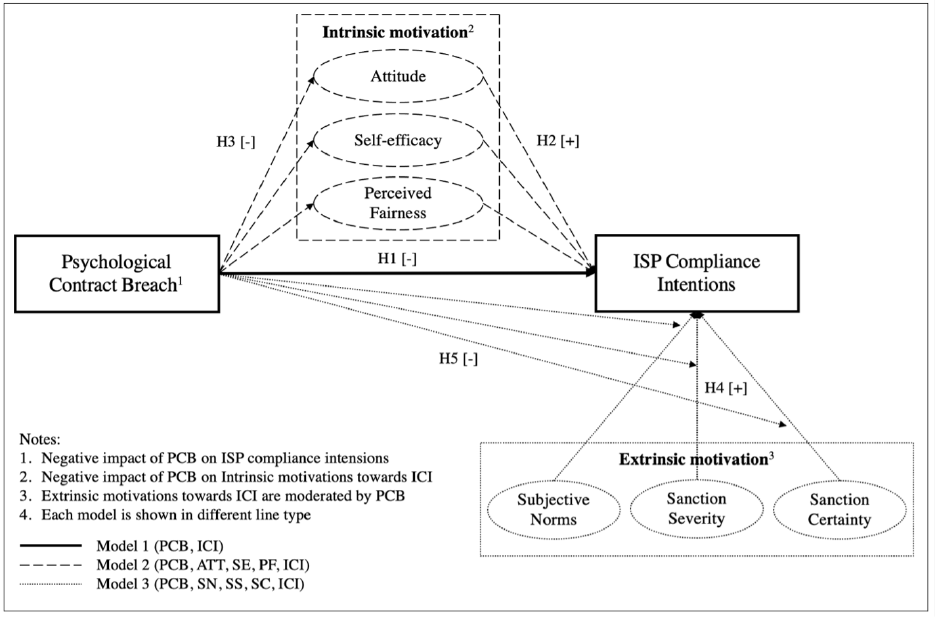

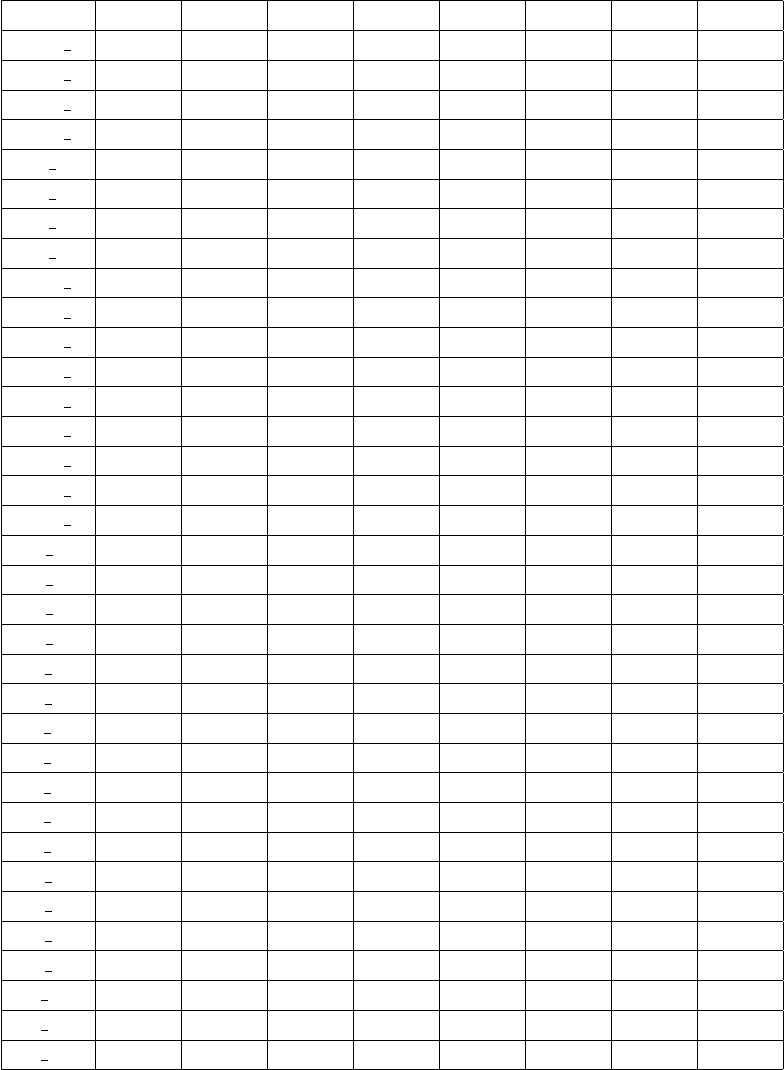

The proposed theoretical framework is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Proposed theoretical framework of the study

2.5 Research Contribution

In an era where most cyber-attack strategies target human weaknesses, it has become imper-

ative for organisations to understand which human factors impact their employees’ security

behaviour and foster their willingness to abide by the security regulations. However, enhanc-

ing employee intention requires more than providing a security awareness program. In order

to properly comply with ISP, firstly, employees should be able to understand and practically

apply the given information. Secondly, they should have attitudes and intentions to willingly

comply with the policies (Bada et al., 2019). However, the attitudes and intentions to com-

ply with ISP are accompanied by multifaceted psychological factors; employees’ evaluation

of their capabilities to obey ISP (self-efficacy), disadvantages when not following the com-

pliance (sanctions), and employees’ perceived expectations of coworkers (subjective norms)

7

(Topa and Karyda, 2015). Many behavioural theories have been researched in the field of

IS security to date, grouping the relevant psychological factors. Among the various theories,

this study will focus on social factors of TPB and GDT, dividing them into intrinsic and

extrinsic motivational factors for ISP compliance intentions.

Meanwhile, although much research has found that many psychological factors affect ISP

compliance behaviour and intentions, there are still potential factors that have not yet been

properly studied. Likewise, no research has yet focused on the direct relation between PCB

and ISP compliance intentions, although some theoretical studies Ertan et al. (2018); Leach

(2003) have implied the important role of PCB against complying with security policies.

Conversely, one research study explored the mediating role of PCF (Psychological Contract

Fulfilment) between perceived costs of Rational Choice Theory and ISP compliance intention.

As a result of the study, the impact of PCF was influential in the supervisor group, but not

prominent in the supervisee group (Han et al., 2017a). However, because they conducted the

research with only limited factors, the influence of the PC in the non-administrator group

was not thoroughly examined.

Accordingly, the research examines the research question: “How does an employee’s

Psychological Contract Breach affect Information Security Policies Compliance Intentions?”

3 Methodology

3.1 Data collection

We used an online survey and recruited an FTSE 250 UK industrial goods and services

company as a partner company for the survey. A single specific company was selected

because it was important to ensure that participants were members of a company which

had an appropriate ISP and that employees are aware of the ISP. Therefore, rather than

distributing the survey to any employees, we decided to partner with a large corporation

that provides a dedicated ISP. The survey was distributed only to employees working in

the UK to facilitate communication and scheduling. A total sample size of 1,000 employees

was selected through simple random sampling from a population of 3,021 employees of the

partner company in the UK. As a result, 265 survey responses were received and only 208

responses were fully completed. Accordingly, the survey response rate was roughly 26.5%

and the survey completion rate was over 78.4%. As a result of simply screening the data,

there was two invalid responses within the 208 completed survey responses. Therefore, 206

completed responses remained valid for data analysis.

3.2 Measures

The questionnaire for this study was developed and combined, adopting reliable existing

studies to collect quantitative data. The questionnaire is divided into the first part for the

personal characteristics and the second part for the factors for substantial analysis. In part

1, a questionnaire for an employee’s demographic characteristics has been asked which are

primarily identified as control variables in relevant empirical studies. Therefore, the following

five variables have been included in the questionnaire. On the other hand, part 2 presents the

8

substantial constructs of this study, consisting of 8 factors - Psychological Contract Breach

(PCB), Attitudes (ATT), Self-efficacy (SE), Perceived Fairness (PF), Subjective norms (SN),

Sanction Severity (SS), Sanction Certainty (SC), ISP Compliance Intention (ICI) - and 35

indicators. The full questionnaire is shown in Appendix A.

3.3 Analysis and Results

The data analysis was conducted, divided into 1) descriptive statistics for identifying per-

sonal characteristics, 2) measurement model analysis for construct validity and reliability, 3)

structural model analysis for hypothesis testing, and 4) bivariate analysis for investigating

the correlation between variables. The study employed IBM SPSS for descriptive statistics

and SmartPLS 3.0 for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

3.3.1 Descriptive Statistics

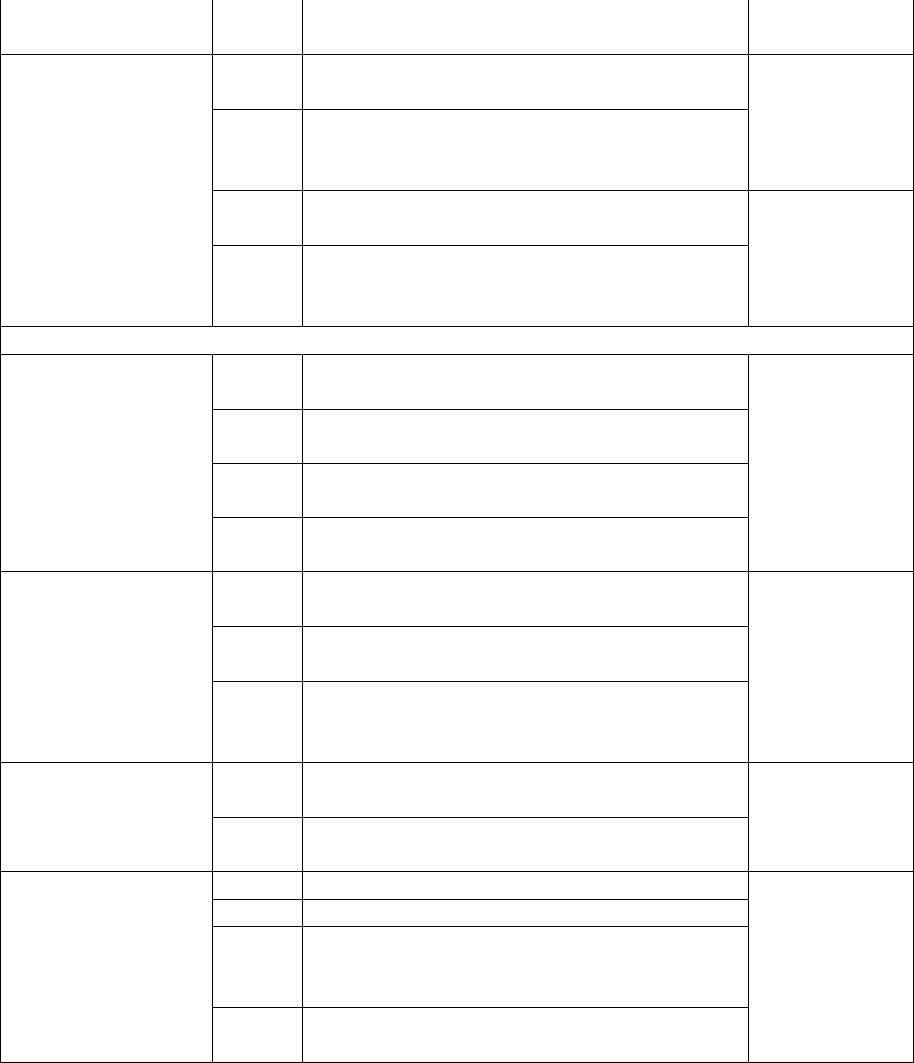

The personal characteristics collected in the Part 1 of the survey are shown in Table 1. The

age group over the age of 19 is almost evenly distributed in all groups except for the oldest age

group. Similarly, responses were received almost evenly from female and male respondents.

By position, there were about twice as many non-managers as managers. Additionally,

more than 40% of respondents have worked for this organisation for one to five years and

rates between about 9% to 21% have been shown in other tenure groups. Lastly, employee

types have been divided into temporary and permanent type, with approximately 90% of

respondents were regular workers.

The normality test results of Part 2 are shown in Table 7 in Appendix B. The mean

value ranged from 1.42 (PCB8) to 2.23 (PCB4) for PCB and from 3.35 (SS2) to 4.83 (ICI1) for

others. These statistics indicate that most respondents had moderately positive responses for

the constructs of the study. The skewness value ranged from -2.862 (ATT2) to 2.354(PCB8),

excluding ATT1 and ICI 1-3. Similarly, the kurtosis value ranged from -0.817 (PCB4) to

9.21(ATT2), except for ATT1 and ICI 1-4. ATT1 and ICI 1-4 failed the normality test since

ATT1 and ICI 1-3 had absolute skewness values greater than or equal to 3.0, and ATT1 and

ICI 1-4 had absolute kurtosis values greater than or equal to 10.0 (Brown, 2015). Therefore,

a linear regression model, which is a non-parametric method that does not require normally

distributed data, was additionally used in this study for variables that failed a normality

test (Fathian et al., 2014).

Additionally, the descriptive statistics, including the mean, minimum and maximum

values of PCB and ICI according to personal characteristics, are described in Table 2.

Firstly, younger groups tend to have higher PCB. Additionally, the older group was more

likely to comply with ISP overall, while the 20-29-year age group (4.78) had almost as high

ICI as the 40-59-year age group (4.76). Secondly, managers (4.78) are more willing to comply

with ISP than non-managers (4.73) although they have higher PCB. By tenure, the group

with the shortest tenure had the lowest PCB (1.23) and ICI (4.71). Lastly, non-regular

workers (1.45) had a much lower PCB level than regular workers (1.81), and their intention

to comply with ISP (4.80) was higher than that of regular workers (4.74). Comparatively,

there was no significant difference by gender in samples.

9

Table 1: Personal characteristics of the survey

Personal characteristics Value Frequency Percent Cumulative Percent

Age

Under 20 0 0 0

20-29 30 14.6 14.6

30-39 51 24.8 39.3

40-49 51 24.8 64.1

50-59 58 28.2 92.2

60 and above 16 7.8 100

Gender

Female 99 48.1 48.1

Male 107 51.9 100

Job position

Manager 67 32.5 32.5

Non-manager 139 67.5 100

Tenure

less than 1 year 18 8.7 8.7

1-5 years 86 41.7 50.5

6-10 years 30 14.6 65

10-15 years 28 13.6 78.6

more than 15 years 44 21.4 100

Employment type

temporary 21 10.2 10.2

permanent 185 89.8 100

Table 2: Descriptive statistics for PCB and ICI according to the personal characteristics

Personal characteristics Value

PCB ICI

Mean Min. Max. Mean Min. Max.

Age

Under 20 N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A

20-29 1.96 1.00 4.33 4.78 3.25 5.00

30-39 1.89 1.00 4.67 4.60 2.00 5.00

40-49 1.76 1.00 4.78 4.76 2.00 5.00

50-59 1.69 1.00 4.22 4.76 1.00 5.00

60 and above 1.50 1.00 3.44 4.91 4.50 5.00

Gender

Female 1.75 1.00 4.33 4.74 1.00 5.00

Male 1.80 1.00 4.78 4.74 2.00 5.00

Job position

Manager 1.86 1.00 4.78 4.78 2.00 5.00

Non-manager 1.74 1.00 4.67 4.73 1.00 5.00

Tenure

less than 1 year 1.23 1.00 2.00 4.71 3.00 5.00

1-5 years 1.85 1.00 4.67 4.75 3.00 5.00

6-10 years 1.95 1.00 4.78 4.80 2.00 5.00

10-15 years 1.89 1.00 3.89 4.85 4.00 5.00

more than 15 years 1.68 1.00 3.56 4.63 1.00 5.00

Employment type

temporary 1.45 1.00 3.33 4.80 3.25 5.00

permanent 1.81 1.00 4.78 4.74 1.00 5.00

10

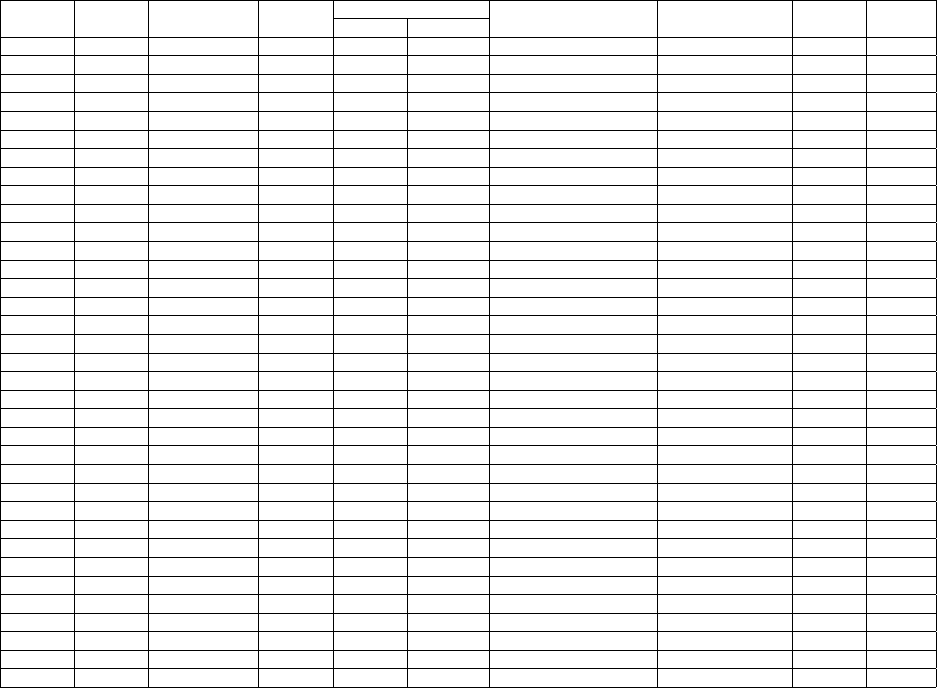

3.3.2 Inferential Statistics

To verify construct validity and reliability, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was per-

formed in this study. The higher the factor loading size (0.8), the better the condition

(Wiktorowicz et al., 2016). However, since the factor loading of 0.4 has been also considered

as significant (MRC, 2013), the construct validity and reliability of all items in this study

are significantly good or moderate, see Table 8 in Appendix C. In Table 9 of Appendix

C, the constructs were additionally verified through multiple measurement models including

Cronbach’s Alpha, rho A, CR, and AVE.

Subsequently, the study analysed motivational process for ISP compliance intention with

various constructs, by dividing into three structural models. The first model consists of PCB

and ICI to investigate the direct correlation between them. In the second model, intrinsic

motivation factors including ATT, SE, PF were added to the constructs in the first model.

The third model was to determine the moderating effect of PCB on the relationship between

extrinsic motivators such as SN, SS, SC, and ICI. The structural models were examined with

T test, path coefficient, and P values to multifaceted investigate the relationships between

factors.

Table 3 shows the result of the structural analysis for the hypotheses of this study. The

direct correlation between PCB and ICI (H1) was verified to be strongly significant with

p values of 0.002. Moreover, with the -0.195 value of path coefficient, the weak negative

effect of PCB on ICI was shown. On the other hand, the relationship between intrinsic

motivation and ICI (H2, H3) was assessed to be partially significant because only ATT

among the three intrinsic motivators was significantly related to ICI. However, ATT-ICI

and PCB-ATT relationships were found to have p values of 0.008 and 0.000 respectively.

Additionally, indirect relationship of PCB-ATT-ICI had p values of 0.028. On the other

hand, the impact of PCB was found to be the most significant on PF through t test and path

coefficient along with p values. However, since PF-ICI relationship was not supported, the

impact of PCB on PF towards ICI was not proved through a structural analysis. Therefore,

while SE and PF were not found to be significant, the impact of PCB on ATT towards

ISP compliance intentions were shown to be very strong. Lastly, among the three extrinsic

motivators (H4, H5), the impacts of both SN and SC on ICI were very strong with p

values of 0.000 and 0.001 respectively, while there was no relevance between SS and ICI.

Comparatively, the moderating effect of PCB was not significant on SN, SS, as well as SC.

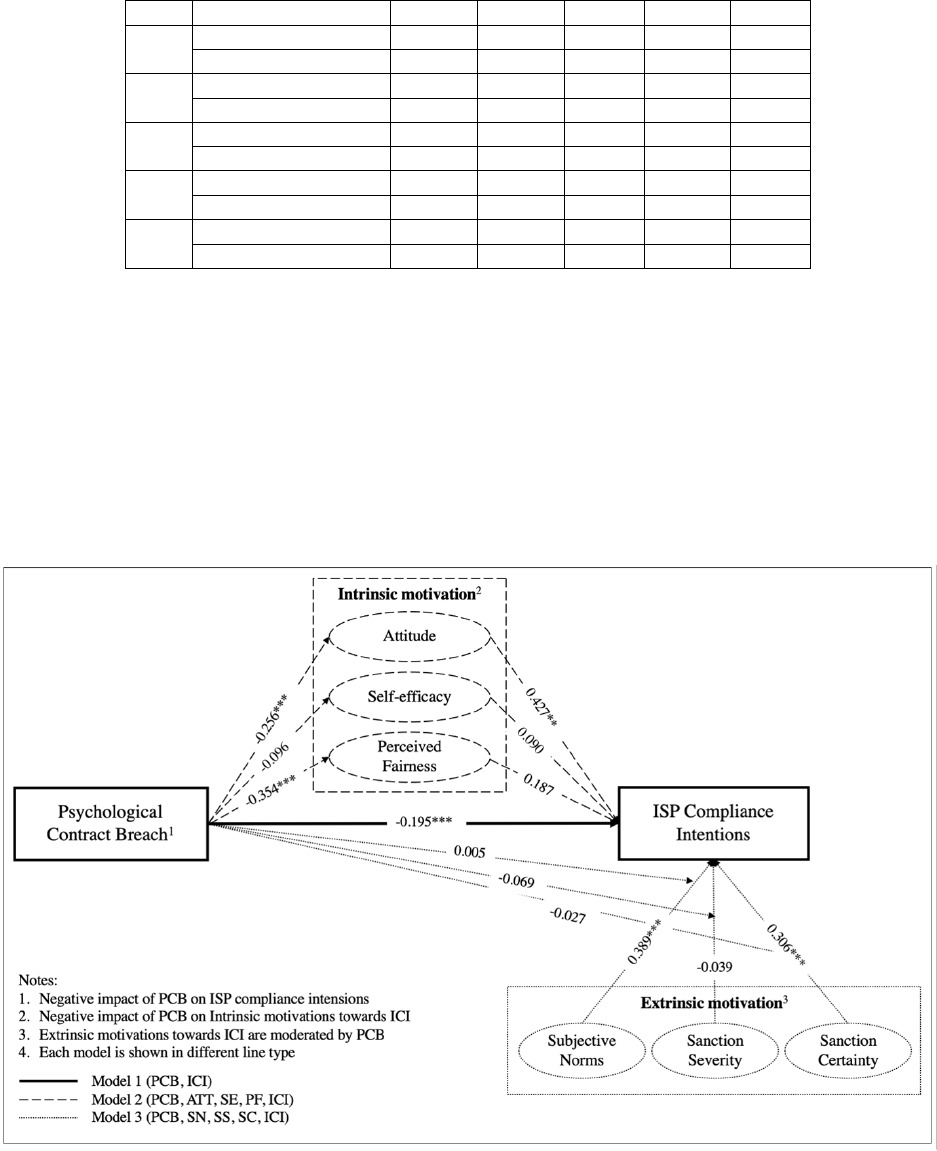

Figure 2 demonstrates the results of statistical analysis based on the theoretical framework

of this study.

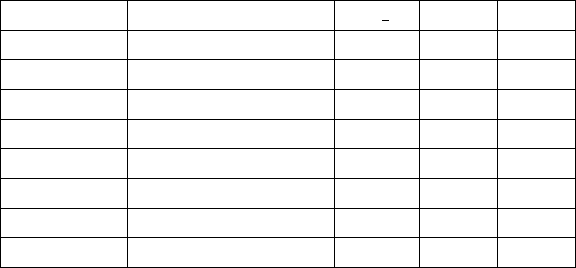

3.3.3 bivariate analysis

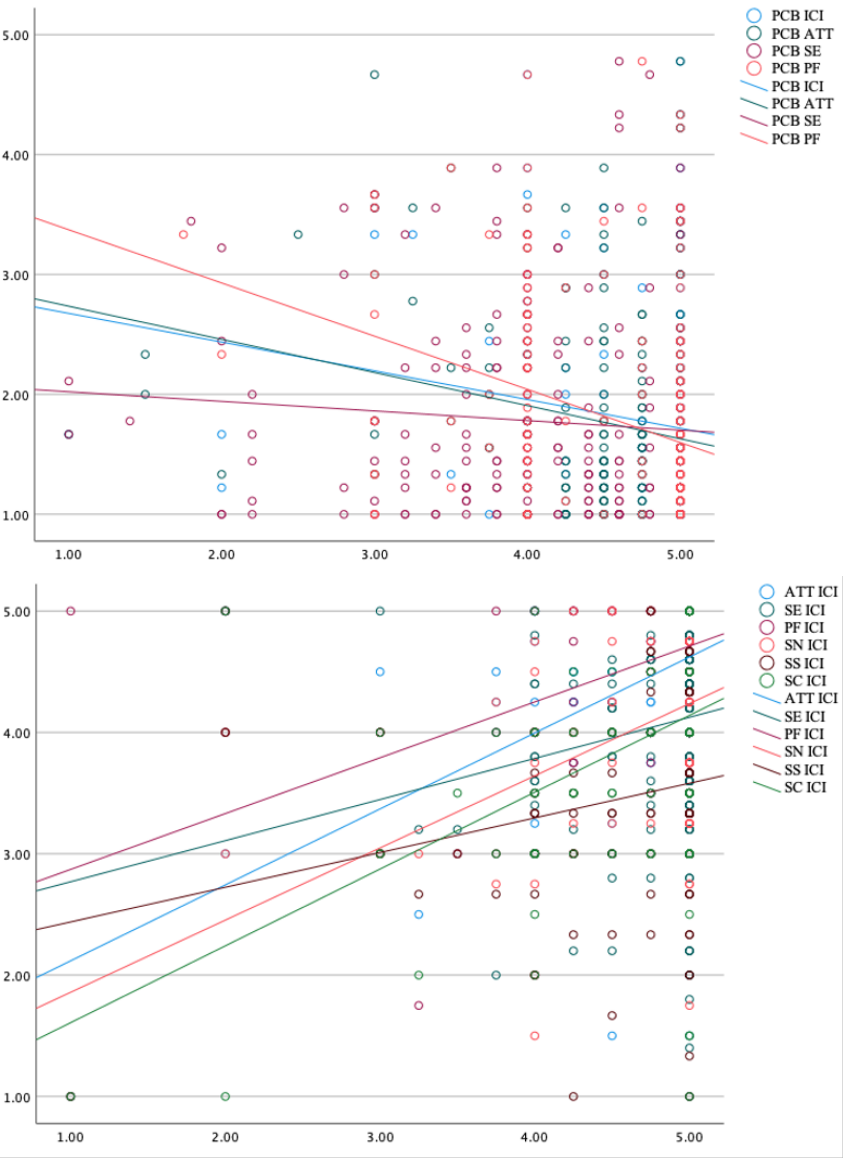

Figure 3 shows scattered plots with simple linear regression analyses. The PCB has negative

correlation with all intrinsic motivation (ATT, SE, PF) as well as ICI, supporting hypotheses

1, 3, and 5. On the other hand, hypotheses 2 and 4 were supported by the positive correlation

between ICI and all constructs except PCB (ATT, SE, PF, SN, SS, SC).

11

Table 3: Pearson correlation coefficient analysis between PCB, ATT, SE, and PF and ICI

PCB ATT SE PF ICI

PCB

Pearson Correlation 1 -.219** -0.078 -.331** -.158*

Sig. (2-tailed) 0.002 0.268 0 0.023

ATT

Pearson Correlation -.219** 1 .300** .496** .520**

Sig. (2-tailed) 0.002 0 0 0

SE

Pearson Correlation -0.078 .300** 1 .193** .230**

Sig. (2-tailed) 0.268 0 0.005 0.001

PF

Pearson Correlation -.331** .496** .193** 1 .407**

Sig. (2-tailed) 0 0 0.005 0

ICI

Pearson Correlation -.158* .520** .230** .407** 1

Sig. (2-tailed) 0.023 0 0.001 0

** Significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

* Significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

4 Discussion

As a result of the hypothesis test, it was found that the intention to comply with ISP

was significantly affected by PCB, ATT, SN, and SC. Firstly, it has been shown that the

higher the PCB of an employee, the more likely they are to be compliant with ISP. Of the

three intrinsic motivators (ATT, SE, PF), only the ATT-ICI relationship was found to be

Figure 2: Structural statistics for theoretical framework of the study

12

Figure 3: Linear regression analysis for the impact of PCB (top) and the predictors of ICI

(bottom)

13

Table 4: Pearson correlation coefficient analysis between SN, SS, and SC and ICI

SN SS SC ICI ICI

SN

Pearson Correlation 1 .254** .346** .433** -.158*

Sig. (2-tailed) 0 0 0

SS

Pearson Correlation .254** 1 .530** .203** .520**

Sig. (2-tailed) 0 0 0.003 0

SC

Pearson Correlation .346** .530** 1 .411** .230**

Sig. (2-tailed) 0 0 0 0.001

ICI

Pearson Correlation .433** .203** .411** 1 .407**

Sig. (2-tailed) 0 0.003 0 0

** Significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

significant while both SE and PF did not appear to affect ICI. In addition, PCB had a great

negative effect on ATT and the indirect relationship of PCB-ATT-ICI was also found to

be significant. Thus, PCB were found to have a negative impact on attitudes towards ISP

compliance intentions. On the other hand, the PF-ICI relationship was too weak to support

the hypothesis although PCB had a negative impact on PF for ISP. Accordingly, only the

impact of PCB on ATT towards ICI was supported in the second model.

Among the three extrinsic motivators (SN, SC, SS), SN and SC showed a positive relation

with ICI as expected by the existing theories. In contrast, the effect of SS on ICI was

not significant. Additionally, the moderating role of PCB between the three factors and

ICI was not significant at all, suggesting that PCB do not moderate the strongly positive

SN-ICI and SC-ICI relationships. Subsequently, H6 was significantly supported. Among

intrinsic motivators, PCB negatively influenced ATT, which had a correlated effect on ICI

to a significant extent. On the other hand, while SN and SC were found to affect ICI

positively, they were not moderated by PCB. This result can be interpreted that PCB

can reduce positive intrinsic motivation for ICI while PCB does not influence the extrinsic

motivation for ICI. Therefore, the effect of PCB on intrinsic motivation is stronger than

the moderating effect of psychological contract breach between extrinsic motivation and ISP

compliance intention.

The Pearson correlation coefficient explained that all relationships in the theoretical

framework of the study are correlated, except for PCB-SE relationship. Additionally, con-

trary to the structural analysis results, the PF-ICI and SS-ICI relationships were shown to

have a significant positive correlation. Furthermore, as a result of simple linear regression

analysis, PCB showed a negative correlation with intrinsic motivation and ICI, whereas all

motivation factors except PCB have a positive correlation with ICI.

To sum up the results, it was confirmed that the negative correlation and causal rela-

tionship between PCB and ICI were significant, verifying hypothesis 1. These results can

contribute to expanding existing research on the negative effects of PCB in organisations.

Second, the study aimed to investigate how psychological factors such as intrinsic and ex-

trinsic motivators for ICI could be negatively affected by PCB. As a result, ATT for ICI was

significantly negatively affected by PCB, suggesting that PCB could decrease positive atti-

tudes towards ICI. Lastly, it was shown that PCB did not moderate the positive correlation

between extrinsic motivation and ICI.

Based on the findings, the study can propose that increasing intrinsic motivation and

14

establishing extrinsic factors for prevent employees with PCB from performing inadequate

cybersecurity behaviour. In particular, organisations should pay attention to fulfil their em-

ployees’ psychological contracts and strive to improve their attitudes for ISP compliance.

Additionally, to address the risk of psychological contract breaches, organisations can en-

courage employees’ extrinsic motivation by building a cybersecurity culture and establishing

certain sanctions for ISP compliance breaches.

5 Conclusions

Most cyber threat actors today often leverage human factors, as known as social engineering

attacks or people hacking, which makes employee ISP compliance much more important.

Nevertheless, not all employees are willing to be ISP compliant as the organisation expects

them to be. Although most employees claim that they do not have enough time to comply

with all ISPs during work, ISP noncompliance is rather driven by a variety of psychological

motivations. Psychological contract breach has emerged as a major issue in the business

environment because it fosters negative employee beliefs against the organisation. There-

fore, the study conducted an empirical study to investigate the effect of PCB on ICI. In

this study, the psychological factors of the Theory of Planned Behaviour and General Deter-

rence Theory were additionally applied by classifying it as intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.

Data analysis primarily revealed that high PCB significantly led to low ISP compliance in-

tentions. As a result, it was found that PCB greatly reduced intrinsic motivation (attitudes

and perceived fairness) for ICI but did not moderate the relationship between extrinsic mo-

tivation (subjective norms and sanction certainty) and ICI. Overall, this study showed that

an employees’ PCB played a significant role in influencing ISP compliance intentions.

5.1 Recommendations

Based on the findings, the study can propose that increasing intrinsic motivation and es-

tablishing extrinsic factors prevent employees with PCB from performing inadequate cy-

bersecurity behaviour. In particular, organisations should pay attention to fulfilling their

employees’ psychological contracts and strive to improve their attitudes for ISP compliance.

Additionally, to address the risk of psychological contract breaches, organisations can en-

courage employee extrinsic motivation by building a cybersecurity culture and establishing

certain sanctions for ISP compliance breaches.

In addition to establishment of ISP, employee ISP compliance is essential to avoid threats

of people hacking and social engineering. Therefore, reducing PCB is important not only for

employee engagement and work performance but also for information security risk manage-

ment. The most important ways to address the risks of employee PCB is to make promises

clear from the beginning. Alternatively, PCB can be mitigated by open communication, trust

in the supervisor, and specific obligations (e.g. job content, career development, organisa-

tional policies, leadership and social contacts, work-life balance, job security, rewards) (van

Gilst et al., 2020). Besides, it was found that the relationship between PCB and work perfor-

mance was moderated in employees having high social interaction, perceived organisational

support, and trust (Bal et al., 2010).

15

Second, organisations should strive to increase positive attitudes and perceived fairness.

In addition to fulfilling the employee psychological contract, a manager’s persuasive strategy

can increase employee attitudes and intrinsic motivation more effectively than an assertive

strategy (Chiu, 2018). In addition, organisations should identify why employees perceive that

the ISP compliance requirements are unfair. Third, the study also suggests that an organ-

isation’s cybersecurity culture can mitigate an employee’s undesirable security behaviours,

which can be caused by high PCB. Organisations must make significant investments in imple-

menting transformational change to build a cybersecurity culture that goes beyond simply

offering a SETA program (Alshaikh, 2020). In addition, despite the PCB, employees are

inevitably inclined to comply with the ISP to avoid their misbehaviours getting caught up.

Thus, the final proposal of this study is to pay attention to employee behaviour and ISP com-

pliance. Organisations can also establish security measures to monitor and alert employees

for breaches of security compliance.

5.2 Limitations and Directions for Future Research

This study conducted a cross-sectional survey that measured only partial and static phe-

nomenon due to the time frame of the study (Bravo et al., 2019). Therefore, the path

coefficient was analysed in order to examine the causal relationship between PCB and mo-

tivators as well as ICI. Nevertheless, the study was unable to identify whether PCB was

created before other psychological factors. Accordingly, a longitudinal study is proposed to

be employed in future research.

In addition, the average value of PCB collected from the partner company was very low

(1.78), while the average ICI was very high (4.74). Therefore, this might have affected the

significance of the impact of PCB on ICI. Out of the 206 valid responses, only 30 employees

had PCBs of 3.0 or higher and 176 employees had PCBs less than 3.0. Therefore, the study

was unable to divide the sample into breached and non-breached groups. Furthermore, only

3 employees had an ICI of less than 3, while 203 employees had an ICI of 3 or much higher.

Such biased data could have affected the significance of relationships between factors. Thus,

in future research, it is desirable to recruit multiple companies to diversify the range of PCB

and ICI. The structural model analysis found that SE, PF, and SS were not significant for

ICI. There were also no significant effects of SE for ICI with correlation efficient although

SE has been long studied to have very strong correlation with ICI in IS studies (Lebek

et al., 2014; Nasir et al., 2017). On the contrary, PF and SS showed a significant correlation

with ICI through correlation coefficient analysis. This can lead to the conclusion that the

relationship between PCB and the three factors were not fully investigated. Therefore,

these relationships should be further investigated in future studies, especially in longitudinal

studies.

References

Franklin Abela and Manwel Debono. The relationship between psychological contract

breach and job-related attitudes within a manufacturing plant. SAGE Open, 9(1):

2158244018822179, 2019. ISSN 2158-2440.

16

Sherly Abraham. Information security behavior: Factors and research directions, 2011.

Hadi AL-Abrrow, Alhamzah Alnoor, Eman Ismail, Bilal Eneizan, and Hebah Zaki Makham-

reh. Psychological contract and organizational misbehavior: Exploring the moderating

and mediating effects of organizational health and psychological contract breach in iraqi

oil tanks company. Cogent Business and Management, 6(1):1683123, 2019. ISSN 2331-

1975.

Rose Alinda Alias et al. Information security policy compliance: Systematic literature review.

Procedia Computer Science, 161:1216–1224, 2019.

Moneer Alshaikh. Developing cybersecurity culture to influence employee behavior: A prac-

tice perspective. Computers & Security, 98:102003, 2020.

Ahmed Alzahrani, Chris Johnson, and Saad Altamimi. Information security policy com-

pliance: Investigating the role of intrinsic motivation towards policy compliance in the

organisation. In 2018 4th International Conference on Information Management (ICIM),

pages 125–132. IEEE, 2018.

Maria Bada, Angela M Sasse, and Jason RC Nurse. Cyber security awareness campaigns:

Why do they fail to change behaviour? arXiv preprint arXiv:1901.02672, 2019.

P Matthijs Bal, Dan S Chiaburu, and Paul GW Jansen. Psychological contract breach and

work performance: is social exchange a buffer or an intensifier? Journal of Managerial

Psychology, 2010. ISSN 0268-3946.

P Matthijs Bal, Rein De Cooman, and Stefan T Mol. Dynamics of psychological contracts

with work engagement and turnover intention: The influence of organizational tenure.

European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 22(1):107–122, 2013. ISSN

1359-432X.

Roland Benabou and Jean Tirole. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. The review of economic

studies, 70(3):489–520, 2003.

Evan M Berman and Jonathan P West. Psychological contracts in local government: A

preliminary survey. Review of public personnel administration, 23(4):267–285, 2003.

Gonzalo A Bravo, Doyeon Won, and Weisheng Chiu. Psychological contract, job satisfac-

tion, commitment, and turnover intention: Exploring the moderating role of psychological

contract breach in national collegiate athletic association coaches. International Journal

of Sports Science & Coaching, 14(3):273–284, 2019.

Timothy A Brown. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford publications,

2015.

Burcu Bulgurcu, Hasan Cavusoglu, and Izak Benbasat. Roles of information security aware-

ness and perceived fairness in information security policy compliance. AMCIS 2009 Pro-

ceedings, page 419, 2009.

17

Burcu Bulgurcu, Hasan Cavusoglu, and Izak Benbasat. Quality and fairness of an informa-

tion security policy as antecedents of employees’ security engagement in the workplace: An

empirical investigation. In 2010 43rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences,

pages 1–7. IEEE, 2010.

Burcu Bulgurcu, Hasan Cavusoglu, and Izak Benbasat. Information security policy com-

pliance: the role of fairness, commitment, and cost beliefs. In MCIS 2011 Proceedings,

2011.

Holly H Chiu. Employees’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivations in innovation implementation:

The moderation role of managers’ persuasive and assertive strategies. Journal of Change

Management, 18(3):218–239, 2018.

Mark Conner. Theory of planned behavior. Handbook of sport psychology, pages 1–18, 2020.

Dirk De Clercq, Inam Ul Haq, and Muhammad Umer Azeem. Perceived contract violation

and job satisfaction: buffering roles of emotion regulation skills and work-related self-

efficacy. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 2019. ISSN 1934-8835.

Annet H de Lange, P Matthijs Bal, Beatrice IJM Van der Heijden, Nicole de Jong, and

Wilmar B Schaufeli. When i’m 64: Psychological contract breach, work motivation and

the moderating roles of future time perspective and regulatory focus. Work & Stress, 25

(4):338–354, 2011.

Amy Ertan, Georgia Crossland, Claude Heath, David Denny, and Rikke Jensen. Everyday

cyber security in organisations, 2018.

Farshad Fathian, Zohreh Dehghan, and Saeid Eslamian. Analysis of water level changes in

lake urmia based on data characteristics and non-parametric test. International Journal

of Hydrology Science and Technology, 4(1):18–38, 2014.

Waldo Rocha Flores and Mathias Ekstedt. Shaping intention to resist social engineering

through transformational leadership, information security culture and awareness. comput-

ers & security, 59:26–44, 2016.

JinYoung Han, Yoo Jung Kim, and Hyungjin Kim. An integrative model of information

security policy compliance with psychological contract: Examining a bilateral perspective.

Computers & Security, 66:52–65, 2017a. ISSN 0167-4048.

JinYoung Han, Yoo Jung Kim, and Hyungjin Kim. An integrative model of information

security policy compliance with psychological contract: Examining a bilateral perspective.

Computers & Security, 66:52–65, 2017b. ISSN 0167-4048.

James R Harrington and Ji Han Lee. What drives perceived fairness of performance ap-

praisal? exploring the effects of psychological contract fulfillment on employees’ perceived

fairness of performance appraisal in us federal agencies. Public Personnel Management,

44(2):214–238, 2015.

18

Tejaswini Herath and H Raghav Rao. Encouraging information security behaviors in or-

ganizations: Role of penalties, pressures and perceived effectiveness. Decision Support

Systems, 47(2):154–165, 2009a.

Tejaswini Herath and H Raghav Rao. Protection motivation and deterrence: a framework

for security policy compliance in organisations. European Journal of Information Systems,

18(2):106–125, 2009b.

Princely Ifinedo. Understanding information systems security policy compliance: An integra-

tion of the theory of planned behavior and the protection motivation theory. Computers

& Security, 31(1):83–95, 2012.

ISF. Human-centred security, 2020. URL https://www.securityforum.org/human-

centred-security-positively-influencing-security-behaviour/.

Douglas J Landoll. Information Security Policies, Procedures, and Standards: A Practi-

tioner’s Reference. CRC Press, 2017.

John Leach. Improving user security behaviour. Computers & Security, 22(8):685–692, 2003.

ISSN 0167-4048.

Benedikt Lebek, J¨org Uffen, Michael H Breitner, Markus Neumann, and Bernd Hohler.

Employees’ information security awareness and behavior: A literature review. In 2013

46th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, pages 2978–2987. IEEE, 2013.

Benedikt Lebek, J¨org Uffen, Markus Neumann, Bernd Hohler, and Michael H Breitner. In-

formation security awareness and behavior: a theory-based literature review. Management

Research Review, 2014.

Tung-Ching Lin, Shiu-Li Huang, and Shun-Chi Chiang. User resistance to the implementa-

tion of information systems: A psychological contract breach perspective. Journal of the

Association for Information Systems, 19(4):2, 2018. ISSN 1536-9323.

Bing Ma, Shanshi Liu, Hermann Lassleben, and Guimei Ma. The relationships between

job insecurity, psychological contract breach and counterproductive workplace behavior.

Personnel Review, 2019. ISSN 0048-3486.

Ke Michael Mai, Aleksander PJ Ellis, Jessica Siegel Christian, and Christopher OLH Porter.

Examining the effects of turnover intentions on organizational citizenship behaviors and

deviance behaviors: A psychological contract approach. Journal of Applied Psychology,

101(8):1067, 2016a. ISSN 1939-1854.

Ke Michael Mai, Aleksander PJ Ellis, Jessica Siegel Christian, and Christopher OLH Porter.

Examining the effects of turnover intentions on organizational citizenship behaviors and

deviance behaviors: A psychological contract approach. Journal of Applied Psychology,

101(8):1067, 2016b.

Arooj Makki and Momina Abid. Influence of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation on employee’s

task performance. Studies in Asian social science, 4(1):38–43, 2017.

19

Elizabeth Wolfe Morrison and Sandra L Robinson. When employees feel betrayed: A model

of how psychological contract violation develops. Academy of management Review, 22(1):

226–256, 1997.

MRC. What thresholds should i use for factor loading cut-offs?, 2013. URL https://

imaging.mrc-cbu.cam.ac.uk/statswiki/FAQ/thresholds.

Akhyari Nasir, Ruzaini Abdullah Arshah, and Mohd Rashid Ab Hamid. Information security

policy compliance behavior based on comprehensive dimensions of information security

culture: A conceptual framework. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on

Information System and Data Mining, pages 56–60, 2017.

Judy Pate, Graeme Martin, and Jim McGoldrick. The impact of psychological contract

violation on employee attitudes and behaviour. Employee Relations, 2003. ISSN 0142-

5455.

Sandra L Robinson. Trust and breach of the psychological contract. Administrative science

quarterly, pages 574–599, 1996.

Sandra L Robinson and Denise M Rousseau. Violating the psychological contract: Not the

exception but the norm. Journal of organizational behavior, 15(3):245–259, 1994.

Sandra L Robinson and Elizabeth Wolfe Morrison. The development of psychological con-

tract breach and violation: A longitudinal study. Journal of organizational Behavior, 21

(5):525–546, 2000. ISSN 0894-3796.

Sandra L Robinson, Matthew S Kraatz, and Denise M Rousseau. Changing obligations and

the psychological contract: A longitudinal study. Academy of management Journal, 37

(1):137–152, 1994.

Denise M Rousseau. Psychological and implied contracts in organizations. Employee respon-

sibilities and rights journal, 2(2):121–139, 1989.

Nader Sohrabi Safa, Carsten Maple, Steve Furnell, Muhammad Ajmal Azad, Charith Perera,

Mohammad Dabbagh, and Mehdi Sookhak. Deterrence and prevention-based model to

mitigate information security insider threats in organisations. Future Generation Computer

Systems, 97:587–597, 2019.

Ioanna Topa and Maria Karyda. Identifying factors that influence employees’ security be-

havior for enhancing isp compliance. In International Conference on Trust and Privacy

in Digital Business, pages 169–179. Springer, 2015.

Jeroen Trybou and Paul Gemmel. The mediating role of psychological contract violation

between psychological contract breach and nurses’ organizational attitudes. Nursing eco-

nomics, 34(6):296–303, 2016. ISSN 0746-1739.

Erika van Gilst, Ren´e Schalk, Tom Kluijtmans, and Rob Poell. The role of remediation in

mitigating the negative consequences of psychological contract breach: a qualitative study

in the banking sector. Journal of Change Management, 20(3):264–282, 2020.

20

Justyna Wiktorowicz et al. Exploratory factor analysis in the measurement of the compe-

tencies of older people. Ekonometria, 2016.

Kirk R Williams and Richard Hawkins. Perceptual research on general deterrence: A critical

review. Law and Society Review, pages 545–572, 1986. ISSN 0023-9216.

HAO Zhao, Sandy J Wayne, Brian C Glibkowski, and Jesus Bravo. The impact of psycho-

logical contract breach on work-related outcomes: a meta-analysis. Personnel psychology,

60(3):647–680, 2007. ISSN 0031-5826.

21

Appendix A

PART ONE: Personal Characteristics

1. What is your age?

[ ] under 20

[ ] 20-29

[ ] 30-39

[ ] 40-49

[ ] 50-59

[ ] 60 and above

2. What is your gender?

[ ] Female

[ ] Male

3. What is your job position?

[ ] Manager

[ ] Non-manager

4. How long have you worked in this organisation?

[ ] less than 1 year

[ ] 1-5 years

[ ] 6-10 years

[ ] 10-15 years

[ ] more than 15 years

5. What is your type of employment?

[ ] Temporary

[ ] Permanent

22

PART TWO: Motivational process for ISP compliance intention

To what extent do you agree?

* ISP (Information Security Policy) prescribes employee’s cybersecurity behaviour within an or-

ganisation (e.g. use of personal computers, access to the internal systems, opening emails and

attachments, data leakage from social media, password management, and software downloads from

the internet).

Table 5: Research Questionnaire

Factor Item Item Description Sources

Psychological

contract breach

PCB1 Almost all the promises made by my em-

ployer during recruitment have been kept so

far. AL-Abrrow

et al. (2019);

Robinson and

Wolfe Morri-

son (2000)

PCB2 I feel that my employer has come through

in fulfilling the promises made to me when I

was hired.

PCB3 So far my employer has done an excellent job

of fulfilling its promises to me.

PCB4 I have not received everything promised to

me in exchange for my contribution.

PCB5 My employer has broken many of its

promises to me even though I’ve upheld my

side of the deal.

PCB6 I feel a great deal of anger toward my organ-

isation.

PCB7 I feel betrayed by my organisation.

PCB7 I feel that my organisation has violated the

contract between us.

PCB9 I feel extremely frustrated by how I have

been treated by my organisation.

Intrinsic Motivation

Attitudes

ATT1 Following the organisation’s ISP is a good

idea.

Ifinedo (2012)

ATT2 Following the organisation’s ISP is a neces-

sity.

ATT3 Following the organisation’s ISP is beneficial.

ATT4 Following the organisation’s ISP is pleasant.

Self-efficacy

SE1 I would feel comfortable following most of

the ISP on my own. Herath and

Rao (2009b);

Ifinedo (2012)

SE2 If I wanted to, I could easily follow ISP by

on my own.

SE3 I would be able to follow most of the ISP

even if there was no one around to help me.

SE4 I believe that it is within my control to pro-

tect myself from information security viola-

tions.

23

SE5 I have the necessary skills to protect myself

from information security violations.

Perceived Fairness

PF1 I believe the requirements of the ISP that I

am required to comply with are unfair. Bulgurcu

et al. (2010)PF2 I believe the requirements of the ISP that I

am required to comply with are unreason-

able.

PF3 I believe the expectations of the organisation

that I should comply with the ISP is unfair.

Self-developed

PF4 I believe the expectations of the organisation

that I should comply with the ISP is unrea-

sonable.

Extrinsic Motivation

Subjective Norms

SN1 My boss thinks that I should follow the or-

ganisation’s ISP.

Ifinedo (2012)

SN2 My colleagues think that I should follow the

organisation’s ISP.

SN3 My organisation’s IT department pressures

me to follow the organisation’s ISPs.

SN4 My subordinates think I should follow the

organisation’s ISP.

Sanction Severity

SS1 The organisation disciplines employees who

break information security rules.

Herath and

Rao (2009b)

SS2 My organisation terminates employees who

repeatedly break security rules.

SS3 If I were caught violating organisation infor-

mation security policies, I would be severely

punished.

Sanction Certainty

SC1 Employee computer practices are properly

monitored for policy violations.

Herath and

Rao (2009b)

SC2 If I violate organisation security policies, I

would probably be caught.

ISP Compliance

Intentions

ICI1 I intend to follow the organisation’s ISP. Herath and

Rao (2009b);

Han et al.

(2017b)

ICI2 I am likely to follow the organisation’s ISP.

ICI3 It is possible that I will comply with ISP to

protect the organisation’s information sys-

tems.

ICI4 I am certain that I will follow organisational

ISP.

Note - 1: Strongly disagree, 2: Somewhat disagree, 3: Neither agree nor disagree, 4: Somewhat

agree, 5: Strongly agree

24

Appendix B

For analysis, the values of PCB 1-3 were reverse coded as PCB represent a negative factor,

whereas PCB 4-9 remained the same. Similar, the values of PF 1-4 were reverse coded as perceived

fairness was a positive motivator. Therefore, a low value for the PCB indicator can be interpreted

as positive, while a high value is associated with a positive factor for the other 25 indicators.

Table 6: Results showing normality test of factors

Indicator

Range

Statistics

Min. Statistics

Max.

Statistics

Mean

Std. Deviation Statistic Variance Statistics Skewness Kurtosis

Statistics Std. Error

PCB1 4 1 5 1.92 0.072 1.04 1.081 1.218 1.055

PCB2 4 1 5 1.96 0.073 1.047 1.096 1.067 0.579

PCB3 4 1 5 2.02 0.069 0.988 0.975 0.851 0.286

PCB4 4 1 5 2.23 0.091 1.303 1.699 0.677 -0.817

PCB5 4 1 5 1.75 0.077 1.101 1.212 1.302 0.617

PCB6 4 1 5 1.52 0.068 0.976 0.953 1.805 2.414

PCB7 4 1 5 1.52 0.07 1.006 1.012 1.95 2.898

PCB8 4 1 5 1.42 0.062 0.889 0.791 2.354 5.352

PCB9 4 1 5 1.67 0.081 1.163 1.352 1.562 1.179

ATT1 4 1 5 4.71 0.049 0.706 0.498 -3.145 11.337

ATT2 4 1 5 4.68 0.051 0.734 0.539 -2.862 9.21

ATT3 4 1 5 4.62 0.054 0.773 0.597 -2.365 5.831

ATT4 4 1 5 3.83 0.07 1.011 1.023 -0.414 -0.469

SE1 4 1 5 4.14 0.064 0.913 0.834 -1.331 1.945

SE2 4 1 5 3.93 0.068 0.97 0.942 -1.06 1.052

SE3 4 1 5 3.91 0.072 1.034 1.07 -1.096 0.956

SE4 4 1 5 4.14 0.067 0.955 0.912 -1.44 2.321

SE5 4 1 5 4.07 0.065 0.935 0.873 -1.222 1.631

PF1 4 1 5 4.53 0.051 0.737 0.543 -1.892 4.577

PF2 4 1 5 4.55 0.051 0.736 0.542 -1.727 3.06

PF3 3 2 5 4.65 0.044 0.629 0.396 -1.812 3.011

PF4 3 2 5 4.65 0.043 0.621 0.386 -1.801 3.084

SN1 4 1 5 4.54 0.055 0.788 0.62 -1.641 2.11

SN2 4 1 5 4.31 0.064 0.922 0.849 -1.186 0.726

SN3 4 1 5 3.54 0.084 1.212 1.469 -0.493 -0.545

SN4 4 1 5 3.95 0.071 1.023 1.046 -0.555 -0.319

SS1 4 1 5 3.44 0.066 0.949 0.901 -0.125 0.09

SS2 4 1 5 3.35 0.061 0.875 0.765 0.138 0.781

SS3 4 1 5 3.73 0.065 0.938 0.88 -0.41 0.121

SC1 4 1 5 3.87 0.065 0.939 0.882 -0.531 0.069

SC2 4 1 5 4.08 0.065 0.936 0.876 -0.995 0.884

ICI1 4 1 5 4.83 0.039 0.56 0.314 -4.567 24.429

ICI2 4 1 5 4.73 0.049 0.708 0.501 -3.386 12.741

ICI3 4 1 5 4.69 0.053 0.765 0.586 -3.096 10.39

ICI4 4 1 5 4.72 0.042 0.598 0.357 -2.858 10.697

25

Appendix C

Table 7: Factor loadings and Cross-loading

ATT ICI PCB PF SC SE SN SS

ATT 1 0.941 0.517 -0.223 0.445 0.291 0.247 0.418 0.126

ATT 2 0.948 0.504 -0.24 0.495 0.29 0.253 0.417 0.124

ATT 3 0.93 0.527 -0.246 0.525 0.346 0.287 0.394 0.155

ATT 4 0.584 0.308 -0.172 0.259 0.321 0.23 0.203 0.19

ICI 1 0.467 0.895 -0.141 0.347 0.372 0.204 0.446 0.159

ICI 2 0.403 0.902 -0.154 0.348 0.338 0.168 0.438 0.18

ICI 3 0.415 0.795 -0.099 0.288 0.267 0.137 0.357 0.146

ICI 4 0.552 0.82 -0.218 0.432 0.476 0.312 0.406 0.26

PCB 1 -0.312 -0.194 0.871 -0.368 -0.376 -0.109 -0.339 -0.21

PCB 2 -0.3 -0.191 0.889 -0.361 -0.361 -0.107 -0.33 -0.195

PCB 3 -0.27 -0.174 0.876 -0.347 -0.334 -0.074 -0.287 -0.161

PCB 4 -0.081 -0.021 0.619 -0.176 -0.179 -0.015 -0.113 -0.084

PCB 5 -0.214 -0.137 0.824 -0.258 -0.286 -0.084 -0.286 -0.185

PCB 6 -0.091 -0.121 0.724 -0.197 -0.255 -0.073 -0.172 -0.235

PCB 7 -0.141 -0.151 0.79 -0.247 -0.265 -0.061 -0.241 -0.257

PCB 8 -0.028 -0.076 0.772 -0.197 -0.199 -0.035 -0.247 -0.237

PCB 9 -0.171 -0.172 0.853 -0.263 -0.278 -0.074 -0.239 -0.264

PF 1 0.461 0.376 -0.367 0.916 0.344 0.185 0.416 0.139

PF 2 0.445 0.365 -0.295 0.908 0.353 0.192 0.353 0.155

PF 3 0.512 0.415 -0.319 0.958 0.33 0.182 0.412 0.099

PF 4 0.499 0.425 -0.342 0.967 0.353 0.184 0.418 0.129

SC 1 0.265 0.356 -0.338 0.327 0.907 0.219 0.335 0.474

SC 2 0.378 0.445 -0.34 0.351 0.941 0.194 0.405 0.52

SE 1 0.306 0.234 -0.096 0.18 0.176 0.868 0.315 0.132

SE 2 0.243 0.216 -0.026 0.17 0.149 0.879 0.236 0.1

SE 3 0.223 0.187 -0.01 0.106 0.156 0.829 0.245 0.092

SE 4 0.234 0.204 -0.161 0.186 0.236 0.853 0.31 0.174

SE 5 0.244 0.231 -0.09 0.191 0.221 0.872 0.298 0.206

SN 1 0.431 0.513 -0.274 0.429 0.388 0.318 0.888 0.193

SN 2 0.406 0.438 -0.343 0.424 0.416 0.322 0.932 0.248

SN 3 0.128 0.207 -0.145 0.106 0.073 0.044 0.507 0.146

SN 4 0.287 0.28 -0.245 0.287 0.296 0.282 0.784 0.27

SS 1 0.125 0.182 -0.224 0.097 0.491 0.152 0.185 0.862

SS 2 0.081 0.127 -0.168 0.025 0.4 0.132 0.131 0.834

SS 3 0.187 0.237 -0.226 0.186 0.477 0.145 0.31 0.873

26

Table 8: Construct validity and reliability

Construct Cronbach’s Alpha rho A CR AVE

ATT 0.877 0.918 0.92 0.748

ICI 0.877 0.889 0.915 0.73

PCB 0.935 0.97 0.943 0.65

PF 0.954 0.957 0.967 0.879

SC 0.831 0.861 0.921 0.854

SE 0.913 0.921 0.934 0.74

SN 0.801 0.902 0.868 0.632

SS 0.826 0.878 0.892 0.734

27