LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCHOLOGICAL CONTRACT VIOLATION:

IMPLICATIONS FOR WORKING MOTHERS,

EMPLOYEE ATTITUDES AND RETENTION

Katherine Barlow

A Dissertation

Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green

State University in partial fulfillment of

the requirements for the degree of

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY

April 2023

Committee:

Margaret Brooks, Committee Chair

Marco Nardone,

Graduate Faculty Representative

Clare Barratt

William O'Brien

© 2023

Katherine Barlow

All Rights Reserved

iii

ABSTRACT

Margaret Brooks, Committee Chair

During the COVID-19 pandemic, remote work became commonplace for many

knowledge workers who were previously office-based. In 2021 and beyond, many organizations

have expected that their employees return to onsite work; much has been unknown, however,

about employee attitudes toward loss of remote work during such a transition. Using the

frameworks of social exchange theory, conservation of resources, and organizational support,

this research seeks to understand how employee attitudes toward remote work may impact

perceptions of psychological contract breach in required return to onsite work.

Although initial hypotheses were not supported, exploratory analyses supported a serial

mediation model in which psychological contract breach, perceived organizational support, and

affective commitment serially mediate the positive relationship between remote work preference

and turnover intent. Positive attitudes of working mothers toward remote work were also

explored, with consideration of how remote work may help in the balance of conflicting home

and work demands. Findings support the unique and valuable role that remote work choice may

play for working mothers as well as illuminating their potential reactions to loss of remote work.

Findings have implications for organizations seeking to meet employee needs and retain

workers, particularly working mothers, when considering work location requirements.

iv

I dedicate this dissertation to my parents, whose belief in me helped me believe in myself too.

And to Sutton, my constant source of support, patience, and encouragement.

Thank you.

v

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many thanks are owed to my committee: Dr. Clare Barratt, Dr. Bill O’Brien, Dr. Marco

Nardone, and especially Dr. Maggie Brooks for their valuable feedback and support throughout

the dissertation process. I would like to extend a heartfelt thank you to all who helped me to

reach potential participants for this research; many family members, friends, coworkers, and

even strangers ensured that my recruiting efforts were successful. I would also like to express my

sincere gratitude to any and all who provided a listening ear, a message of encouragement, or a

vote of confidence throughout this long process.

vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1

Attitudes Toward Remote Work ............................................................................. 4

Return to Site and “The Great Resignation” ................................................. 7

Remote Work and Perceived Organizational Support............................................... 8

Social Exchange Theory .............................................................................. 10

Reciprocity Norm ....................................................................................... 12

Psychological Contract ........................................................................................... 13

Remote Work Transition as Psychological Contract Breach.......................... 15

Outcomes of Contract Breach........................................................... 16

Hypothesis 1 ........................................................................ 18

Hypothesis 2 ........................................................................ 18

Differential Impact ................................................................................................. 18

Working Mothers ........................................................................................ 18

Working Mothers’ Remote Work Preference .................................... 20

Hypothesis 3 ........................................................................ 22

Social Exchange: Valued Resources ............................................................ 22

Broken Reciprocity and Contract Breach .......................................... 23

Hypothesis 4 ........................................................................ 24

Hypothesis 5 ........................................................................ 24

METHOD ................................................................................................................................. 25

Participants ............................................................................................................ 25

Sample ...................................................................................................... 26

vii

Procedure ..................................................................................................................... 28

Measures .................................................................................................... 29

Remote Work Preference ................................................................. 29

Self-Rated Performance ................................................................... 29

Perceived Organizational Support..................................................... 29

Social Exchange Relationship .......................................................... 30

Psychological Contract Breach ......................................................... 30

Psychological Contract Violation ..................................................... 30

Organizational Commitment ............................................................ 30

Turnover Intent................................................................................ 31

Personal and Family Demographics.................................................. 31

Analyses ..................................................................................................... 31

RESULTS ................................................................................................................................ 33

Preliminary Results ................................................................................................ 33

Hypothesis Testing ................................................................................................. 33

Exploratory Results ................................................................................................ 36

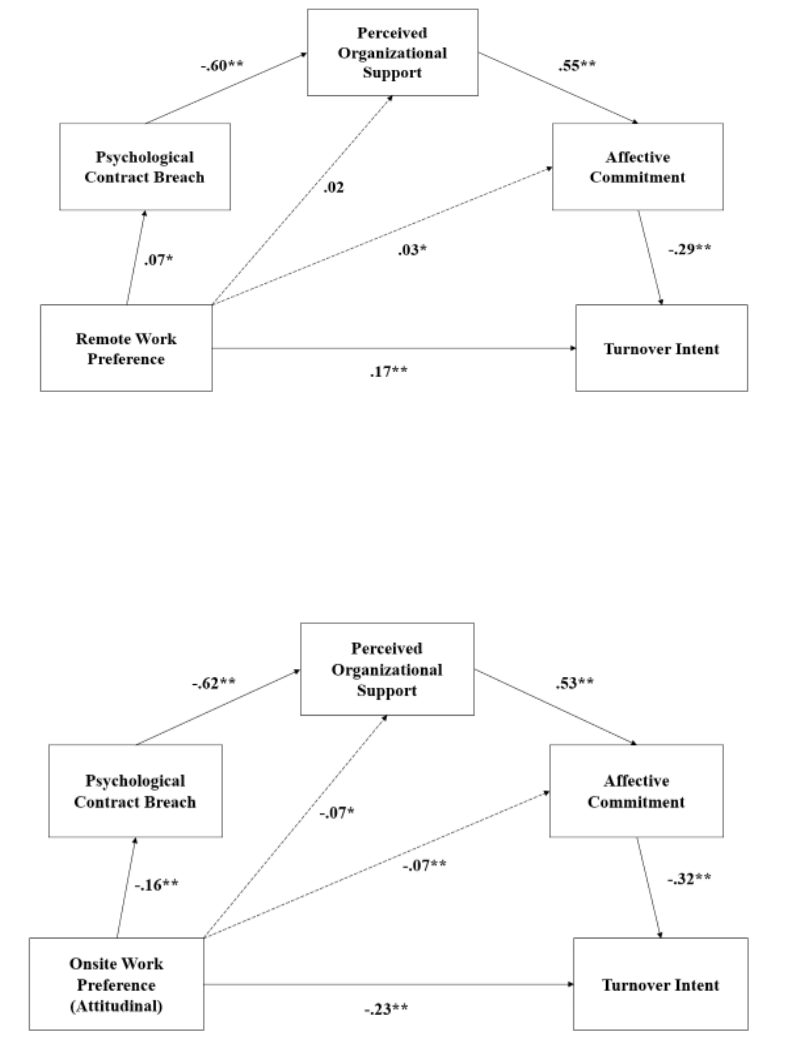

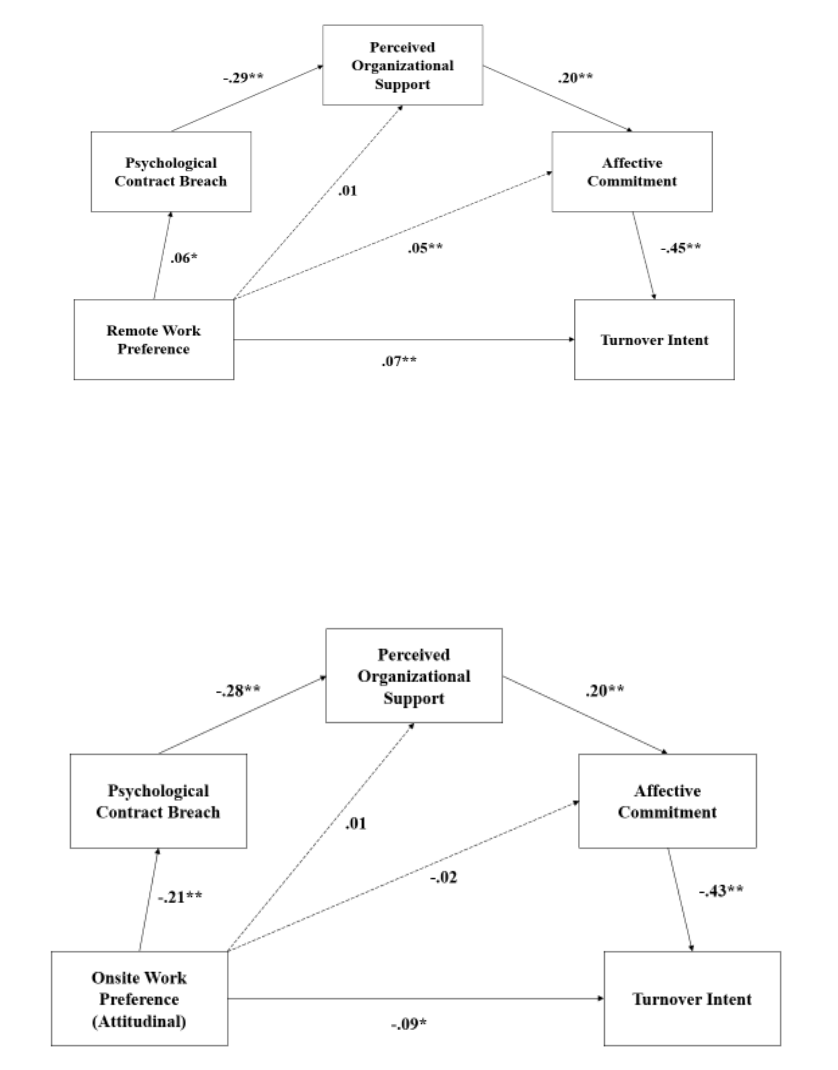

Exploratory Remote Work Preference-Turnover Intent Model ...................... 37

Participants Working Onsite At Least 50% ....................................... 37

Participants Working Onsite Less Than 50% .................................... 38

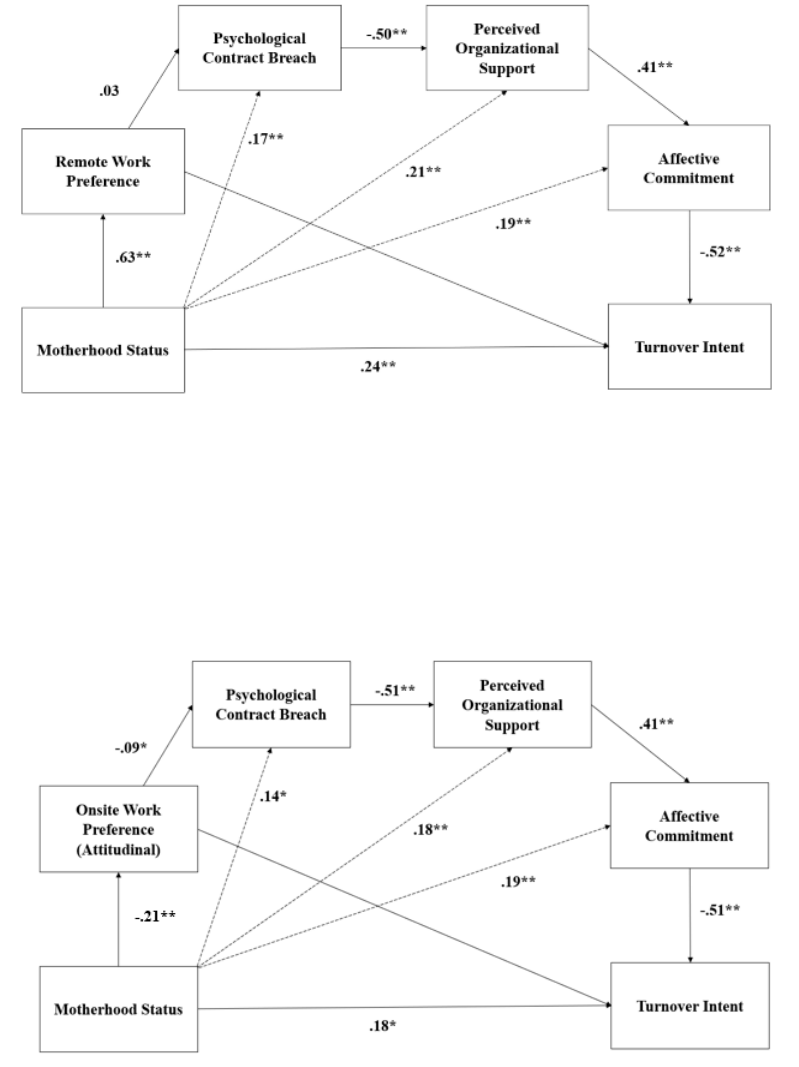

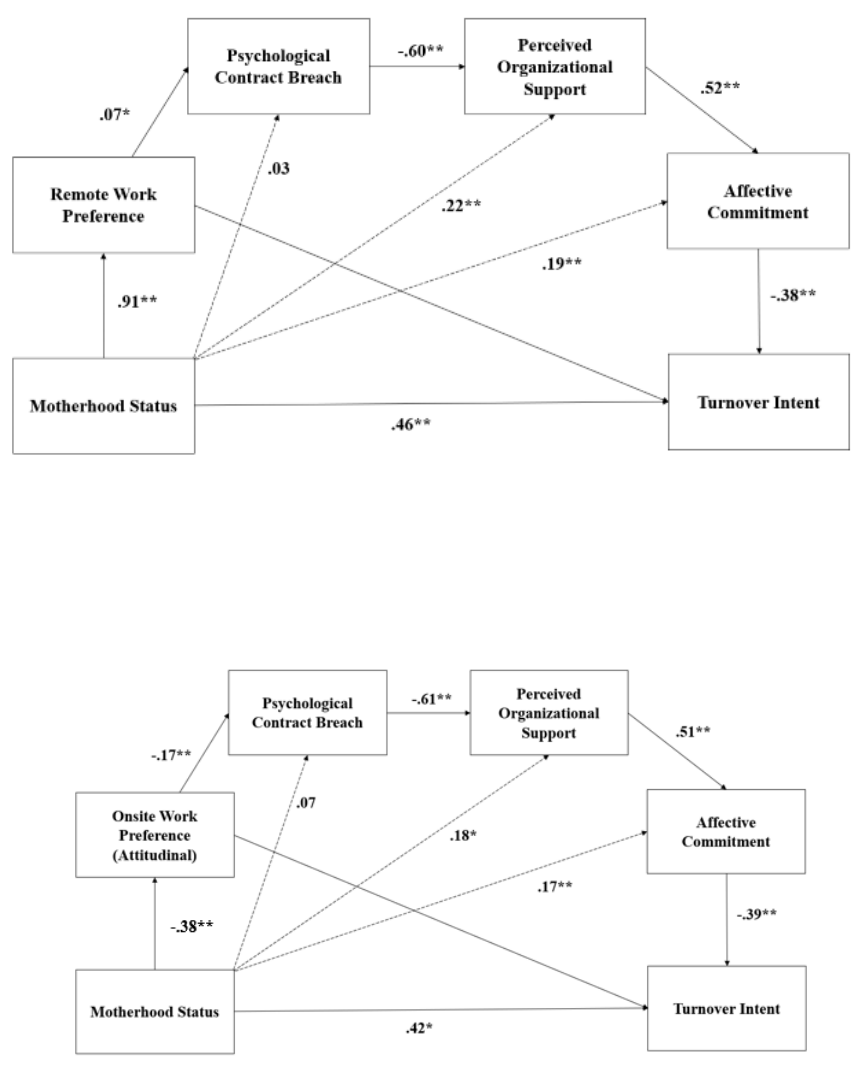

Exploratory Motherhood-Turnover Intent Model.......................................... 39

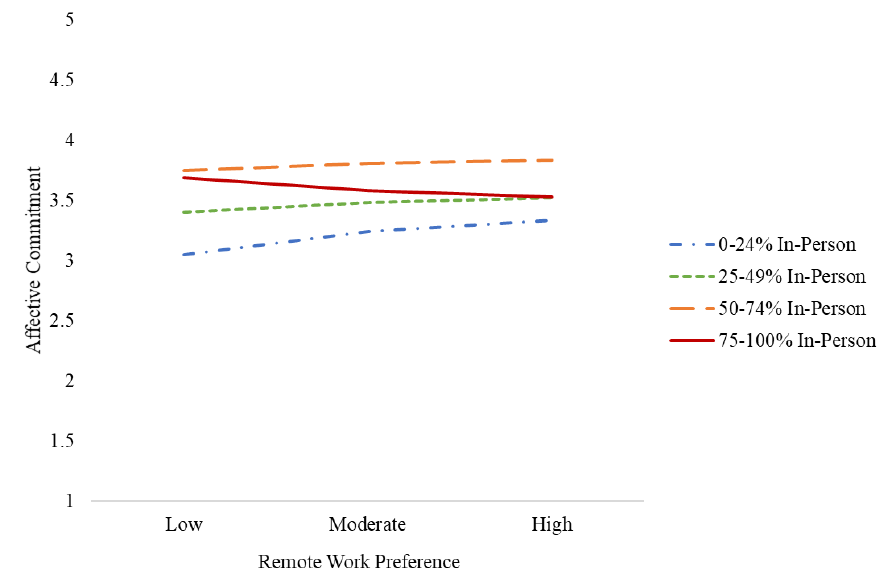

Role of Affective Commitment.................................................................... 40

DISCUSSION.......................................................................................................... ................. 43

Motherhood and Remote Work ............................................................................... 49

viii

Theoretical and Practical Implications..................................................................... 52

Limitations and Future Research ............................................................................. 57

Conclusion .................................................................................................................. . 60

REFERENCES......................................................................................................................... 62

APPENDIX A. MEASURES ............................................................................................. 85

APPENDIX B. TABLES ................................................................................................... 88

APPENDIX C. FIGURES.................................................................................................. 91

Running head: LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 1

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic has been called “the great work-from-home experiment,”

(Kramer & Kramer, 2020). Prior to the pandemic, a very small proportion of the workforce

completed their work remotely, with just 5% of paid work hours completed at home (Barrero et

al., 2021). The novel coronavirus pandemic caused large swaths of knowledge workers,

previously office-based, to transition suddenly to remote work primarily completed at home

(Waizenegger et al., 2020). Among employees whose work can be done from home, the

proportion working remotely or teleworking more than quadrupled since 2010 (Bloom, 2020;

Parker et al., 2020), and the average number of paid hours worked from home jumped from 5%

to 50% in 2020 (Barrero et al., 2021).

Despite the dramatic change in the structure of work in recent years, much has remained

unknown about the challenges and benefits of working from home, shifting employee attitudes

toward remote work, and unique telework factors impacting women and caregiv ers. As

organizations seek to understand the unique return-to-site transition, existing research on remote

work, gender, workplace benefits, and implicit promises made by organizations can help to guide

decision-makers.

Previous research has identified that remote work may play a positive role in job

attitudes, work-family conflict, and decisions to stay with an organization, with mechanisms

including decreased work exhaustion and greater autonomy (Golden, 2006; Gajendran &

Harrison, 2007). As the prevalence of remote work has grown, researchers have begun to explore

how the transition to telework during early 2020 may have influenced worker attitudes toward

their employers (e.g., Gong & Sims, 2021; Zhang et al., 2021). Significant gaps remain,

however, in collective understanding of how transitions back to onsite work following loosened

2 LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION

COVID-related restrictions, and especially those mandatory transitions back to in-person work,

might impact workers.

With so many workers experiencing significant remote work for the first time in 2020,

attitudes toward telework have likely developed and solidified; even so, research on telework

remains behind, failing to reflect changing sentiments caused by sudden transitions in the past

three years (Howe et al., 2020). As employee attitudes have changed and the working world

faces a significant transition point in considering how to navigate work location choices post-

COVID, gaps remain in our understanding of potential impacts. For example, it is currently

unknown whether workers may perceive required return to site as the removal of a valued

resource or simply a return to normalcy. In the context of the ongoing exchange of resources

between employer and employee, it is unclear whether flexibility and telework options are seen

as employee benefits that may “tip the scale,” encouraging workers to stay in their current

organizations and perform well. Further gaps exist in potential implications for caregivers, who

have experienced great challenges during COVID-19 and who may have firmly held attitudes

toward remote work. If organizations wish to prevent rising attrition, negative employee

attitudes, and greater challenges for caregivers, these gaps in understanding must be addressed.

This research therefore aims to explore how preference for remote work relates to worker

attitudes among those who have been required to return to office or onsite work. Using the

framework of social exchange theory, it explores the possibility that employees may perceive

removal of remote work options as a psychological contract breach, a broken promise by

organizations who created implicit understandings that they would continue to exchange this

potentially valued resource for employee performance, commitment, and retention. This study

seeks to understand whether preference for remote work influences perceptions of psychological

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 3

contract breach in the loss of remote work, upsetting the balance of mutual resources provided by

employer and employee. This research can then increase our understanding of negative outcomes

including decreased commitment and increasing turnover intentions.

This study also seeks to fill gaps in the fledgling literature about the impact of remote

work on diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts, specifically in terms of retaining mothers and

other caregivers. While previous research points to gendered preference for remote work (e.g.,

Mokhtarian et al., 1998), much is still unknown about the preference for remote or onsite work

by caregivers. Using the same social exchange framework, this study therefore explores whether

greater preference for remote work among mothers may lead to greater attrition of those mothers

from organizations experiencing a required return to onsite work. If mothers more strongly prefer

remote work, they may be more likely to perceive the expected transition to onsite work as a

broken promise, leading to more severe negative reactions. Understanding the differential impact

of required return to site is vital not only for overall employee attitudes and retention, but also for

ensuring mothers do not have to leave a workforce that is often unaccommodating of caregiving

responsibilities.

As organizations choose how best to transition post-COVID, more research is needed to

better understand potential impacts of the return to onsite work, particularly for turnover risk and

workplace inequality (Maurer, 2021; Lord, 2020). At the time of this transition, this research can

begin to fill gaps in understanding, helping to guide organizations and provide employees what

they value most from work. Using previous research in the fields of remote work, caregiving,

and employee attitudes, this study can build upon existing knowledge, creating a more

comprehensive understanding of the impacts of remote work on employees everywhere.

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 4

Attitudes Toward Remote Work

For the purpose of this study, the terms telework and remote work will be used

interchangeably, as is customary in previous research in the field. Remote or telework includes

work completed via communication technology outside of the primary or central workplace

(Bailey & Kurland, 2002). While public health interventions and state-wide policies pushed

organizations to send their workers away from typical workplaces in 2020, employer attitudes

have historically varied widely in perceptions of remote work. While some recognize the

changing nature of work and potential benefits of telework, many employers have historically

hesitated to allow full-time or even part-time work from home.

Even as some employers hesitate to provide remote work options, increasing

globalization and technical advancement make telework increasingly efficient (Forgács, 2010).

Many employers see potential benefits of increased telework in the form of reduced real estate

costs and lesser ecological footprint (Lord, 2020). In a remote work meta-analysis, Martin and

MacDonell (2012) found that remote work participation demonstrates small but positive

relationships with beneficial employee outcomes including perceived productivity, retention,

organizational commitment, and performance across the organization. Remote work options are

seen as a benefit or perk of employment by many skilled applicants, and filling remote positions

may be simpler for organizations than filling onsite roles, especially for roles requiring

specialized knowledge (Clancy, 2020; Shelburne et al., 2022). Organizations and executives

have also shared positive sentiment about the shift to remote work despite challenges related to

the pandemic, with one estimate stating that 83% found their shift to remote work successful

(Caglar et al., 2021).

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 5

Employers’ increasing willingness to provide telework options may also be a response to

growth in the popularity of remote work among workers. Despite the sudden transition and

complications created by COVID-19, employee responses to remote work have been

overwhelmingly positive. By one estimate, 59% of U.S. workers who worked from home during

the pandemic would prefer to continue remote work after the pandemic subsides (Bren an, 2020).

Even during times of enforced remote work in the early part of the pandemic, sentiment toward

remote work itself was primarily positive (Zhang et al., 2021), and as public health interventions

are lifted, workers are increasingly working remotely due to choice or preference rather than

requirement (Parker et al., 2022). Previous research in the realm of remote work has noted

largely positive outcomes for teleworkers, from positive affective well-being to increased job

performance and creativity (Anderson et al., 2014; Vega et al., 2014). Employees who

voluntarily utilize telework report more efficient performance, better concentration, fewer

distractions, increased work-life balance, greater autonomy, and lower stress (Virtanen, 2020;

Brenan, 2020). Flexibility in the form of remote work choice decreases employees’ work-family

conflict and subsequent turnover intention (Porter & Ayman, 2015). Organizations permitting

telework have lower voluntary turnover than those without remote work options, and employees

working remotely report greater job performance, higher intent to stay, and better balance of

work with dependent care responsibilities (Choi, 2020; Major et al., 2008). Telework can be

particularly helpful as a form of idiosyncratic deal, or adapted work arrangement created to

address individual employee needs (Hornung et al., 2009).

Despite demonstrated positive effects, particularly for employees who voluntarily choose

telework, the choice to permit remote work is most often made by supervisors or the organization

broadly rather than by individual employees themselves (Kaduk et al., 2019; Hill, 2021).

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 6

Concerns about loss of control over employee activities and missed collaboration opportunities

have stopped companies from implementing widespread remote work in the past (Allen et al.,

2015). Other organizations have avoided telework due to concerns about corporate culture,

communication difficulties, or employee motivation while working from home (Forgács, 2010).

Managers and executives may also recognize that remote work is not a blanket solution to

employee problems such as stress, work-family conflict, and communication challenges (Greer

& Payne, 2014). Even as remote work may be viewed as a source of flexibility by some, others

may experience challenges caused by it; involuntary remote work in particular can increase

work-family conflict, stress, burnout, and turnover intentions (Kaduk et al., 2018).

Another large obstacle to remote work is approval of individual managers; factors such as

trust in employees, willingness to delegate power, and concerns about communication may cause

managers to resist allowing long-term remote work (Kaplan et al., 2018; Peters & Den Dulk,

2003). Managers may feel disconnected from subordinates that work remotely, and teleworkers

may feel socially isolated, leading to concerns that they will not be considered fairly for

promotions or other opportunities (Golden et al., 2008; Mayurama & Tietze, 2012). As the

pandemic has subsided in some locations and others learn to live with an ever-present COVID-

19, these same concerns—loss of control, connection, and communication—may motivate

organizations to bring employees back for onsite work.

While research on remote work has grown in past decades, the onset of widespread

telework during the COVID-19 pandemic has created the opportunity for even greater

exploration into employee experiences of remote work. Most office-type work has historically

revolved around an in-person structure, making telework a common experience for only a small

subset of employees prior to 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic created a paradigm shift, a novel

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 7

and disruptive event that shifted assumptions about work; by giving more employees than ever

before the chance to experience remote work, attitudes toward telework have undoubtedly

changed (Howe et al., 2020; Min et al., 2021). Prior research has shown that workers that have

never experienced telework tend to underestimate positive and overestimate negative experiences

they might have while working remotely (Maruyama & Tietze, 2012). With more employees

recently experiencing telework, many will have new or changing attitudes and perceptions

toward remote work. Understanding the implications of these changing attitudes is vital for

organizations who hope to attract high performers and retain employees in years to come.

Return to Site and “The Great Resignation”

As safety standards and understanding of COVID-19 evolve, organizations will continue

to weigh the potential costs and benefits of remote work. Many organizational leaders,

accustomed to and familiar with the benefits of onsite work, have advocated for transitions back

to office and a perceived return to normalcy. As of early 2022, an estimated 67% of remote and

hybrid workers had plans to return to onsite work, often due to organizational requirements

(Qualtrics, 2022). Throughout the past two years, the transition back to onsite work has proven a

key inflection point in the careers of many. In what has been referred to as “The Great

Resignation,” employees across the labor market have expressed greater intent to leave their jobs

and have had increasing opportunities to be selective about the characteristics of their careers—

including work location choice (Anderson & Klotz, 2021).

Human resources professionals and news sources alike have speculated about growing

choice in the job market, employee reflections about long-term career and life decisions during a

period of great health risk, childcare costs, and desire for meaningful, flexible work as potential

drivers of increasing attrition (Patton, 2021). Organizations losing large numbers of employees

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 8

experienced growing costs including training, recruiting, hiring replacements, loss of key

knowledge, and more (Tziner & Birati, 1996). In attempting to understand and prevent increases

in costly attrition, organizations must continue to evaluate the needs and wants of their

employees, particularly during key transition periods (Marsden, 2016).

Remote Work and Perceived Organizational Support

While multiple internal and external factors will inevitably impact employees’ turnover

decisions, organizations certainly have influence on the attitudes of their workers, making long-

term retention possible. One critical component of workers’ commitment to stay at their current

organization is perceived organizational support, or POS. Perceived organizational support

encompasses employee attitudes on the extent to which their employer values their contributions

and cares for their well-being (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002). Research on POS began with the

observation that commitment in both directions was necessary for a healthy work dynamic—not

only from employee to organization, but also from organization back to employee. According to

organizational support theory, employees seek to meet needs of esteem, affiliation, and approval

at work, assessing whether the inputs of their work are met with appropriate support from their

organizations in response (Eisenberger et al., 1986).

Antecedents of POS found across prior research include perceived supervisor support,

and to a lesser extent, team and coworker support (Kurtessis et al., 2017). Additional predictors

include justice perceptions, value and belief congruence with the organization, leader

consideration, or the extent to which leaders show concern for employee well-being and

demonstrate support, and fulfillment of perceived organizational obligations in the form of

psychological contracts (Kurtessis et al., 2017; Rhoades et al., 2002). Psychological contracts

reflect understandings of mutual obligation between organization and employee as part of an

9 LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION

ongoing, social exchange relationship. The perception that these obligations or promises have

been kept is vital to POS, while psychological contract breach has been shown to negatively

impact POS. Job security, flexible work schedules, family supportive company practices,

enriching job characteristics, and greater autonomy at work have also been shown to contribute

to greater perceptions of organizational support, especially when seen as outcomes of voluntary

choice by the organization rather than circumstances outside the organization’s control

(Kurtessis et al., 2017; Rhoades et al., 2002).

Greater perceived organizational support is associated with higher job satisfaction, in-role

and extra-role job performance, and affective organizational commitment, or emotional

attachment to one’s company (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002). Employees who perceive support

from their organizations can be expected to care about the organization’s welfare in return,

rewarding the company for their support due to a reciprocity norm (Rhoades, 2002). Affective

commitment caused by greater POS has been shown to decrease turnover intent, making

organizational support a key intervention point for companies concerned about potential

increases in attrition (Maertz et al., 2007). Greater POS among employees also predicts a social

exchange relationship rather than economic exchange between employee and employer

(Kurtessis et al., 2017). Social exchange relationships emphasize trust, long-term investment, and

mutual obligation, while purely economic exchanges focus on a short-term, clearly specified

exchange of resources alone (Colquitt et al., 2014).

As workplace structures have begun to change and competition for skilled workers

remains high, employees expect organizational support to be conveyed in many forms, including

in gestures of respect and resource provision (Chernyak-Hai & Rabenu, 2018). Modern

workplace rewards, including flexibility and benefits, reflect organizational sensitivity and leader

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 10

concern, or the ways in which an organization and its leaders are aware of and sensitive to the

contributions of an increasingly diverse workforce (Chernyak-Hai & Rabenu, 2018). Employees

may perceive remote work as a valuable, modern reward and source of flexibility that their

organization provides due to trust in and commitment to their employees. By providing workers

with resources such as flexible work arrangements and remote work choice, employers may

promote perceptions of support, creating an ongoing positive relationship with employees

(Eisenberger et al., 2001).

Social Exchange Theory

The employer-employee relationship and methods of retention can be further understood

in the framework of social exchange theory (SET). According to social exchange theory,

relationships are based on an ongoing cost-benefit analysis between each party, with repeated

exchanges of money, goods, services, information, status, or commitment (Homans, 1958;

Cropanzo & Mitchell, 2005). The origins of SET can be traced back as far as the 1920s, when

social psychologists, anthropologists, and sociologists observed that a series of interactions

tended to engender obligations between two parties (Emerson, 1976; Cropanzo & Mitchell,

2005). Within social exchange theory, interactions are understood to be dependent upon the

actions of the other party, with the potential to develop high-quality relationships from ongoing,

beneficial exchanges. These relationships can evolve over time into mutual commitments

governed by implicit rules and norms such as reciprocity, or repayment in kind, as well as formal

negotiated guidelines (Gouldner, 1960; Cropanzo & Mitchell, 2005). In a social exchange

relationship, mutual investment is shaped by the reciprocity norm, with both parties contributing

resources and receiving resources in return in order to maintain mutual benefit (Cropanzo &

Mitchell, 2005).

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 11

Social exchange theory is a helpful framework for understanding the ongoing interactions

between employer and employee. Relationships between organizations and their employees take

one of two forms: transactional, short-term economic relationships or ongoing, norms-based

social exchange relationships (Homans, 1958). The ideal relationship between workers and their

organization is one of mutual investment, with both parties understanding reciprocal obligation

and social exchange associated (Tsui et al., 1997). Organizations and employees make ongoing

exchanges of resources including money, support, performance, and commitment; these

exchange experiences lead to expectations about the relationship and future exchanges

(Cropanzo & Mitchell, 2005). Over time, social exchange relationships between organizations

and employees develop an implicit reciprocity norm, or unwritten expectation that resources

provided by one party will be met with resources from the other (Molm, 2003).

This reciprocity norm can be seen in response to perceived organizational support; when

organizations provide beneficial resources to employees, POS grows, and so too does

employees’ felt obligation to reciprocate. Workers who feel their organization cares for them will

typically demonstrate greater commitment and job performance in return (Eisenberger et al.,

2001; Kurtessis et al., 2015). Similarly, employees who continuously perform well, provide

value, and demonstrate commitment expect ongoing support and resources to be provided by

their organizations (Cropanzo & Mitchell, 2005). If organizations wish to maintain performance

and prevent withdrawal among employees, they must ensure that workers perceive the

organization as a source of support, resources, mutual investment, and fair ongoing exchange. To

promote perceptions of benefit, employers must maintain the reciprocity norm, ensuring ongoing

benefits for employees who continue to prove their loyalty and performance to the organization.

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 12

Reciprocity Norm

Within the context of a social exchange relationship, employees come to expect

reciprocity, or resources given by the organization in exchange for the performance and

commitment workers provide (Eisenberger et al., 2001). Past experiences influence expectations

of reciprocity and understanding of what exchanges the relationship entails (Chernyak-Hai &

Rabenu, 2018). During the COVID-19 pandemic, organizations began permitting or even

requiring remote work; experiences of remote work have likely influenced employee attitudes

about teleworking (Fazio & Zana, 1981). Having experienced remote work, employees may now

understand its benefits and expect opportunities to work remotely as valued resources their

organizations provide as part of the ongoing social exchange.

Expectations of reciprocity may also be influenced by employees’ perceptions of their

own inputs to the mutual exchange in the recent past; workers who have continued to prove their

performance during the pandemic may see remote work option as a resource they have earned.

According to one large-scale study, 90% of organizations surveyed during the pandemic reported

similar or greater worker productivity during remote work periods compared with years prior to

COVID-19 (Ketenci, 2021). For the many employees who have continued to input high-value

resources such as increasing performance, time, and productivity into the social exchange

relationship, removal of resources like remote work could be seen as incompatible with the

reciprocity norm and the social exchange relationship itself (Eisenberger et al., 2001).

In the context of the modern workplace, organizations which provide remote work choice

may be perceived as providing greater support and beneficial resources to employees.

Particularly for those workers who developed positive attitudes toward remote work during the

pandemic, telework may have value as part of the ongoing exchange of resources between

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 13

organization and employee. As part of the exchange governed by reciprocity norms, remote work

option may be a key component in maintaining equitable, fair exchange between employer and

employee. Removing this resource during or after the COVID pandemic could disrupt the

balance in the social exchange relationship; if employees have continued to perform well during

the pandemic, they may question why valuable resources have been taken from them.

Psychological Contract

The reciprocity norm in social exchange relationships, including between organization

and employee, can be further explored in the framework of psychological contracts. First applied

to the workplace context by Argyris in 1960, psychological contracts reflect individual beliefs

about the implicit rules governing the continuous exchange between employer and employee.

Repeated interactions and the ongoing relationship between organization and workers create

expectations about the implicit guidelines of these exchanges, including the norm of reciprocity

(Rousseau, 1989). As employment relationships are created and maintained between

organizations and individuals, each brings expectations of mutual obligations and promises

beyond the explicit requirements outlined in formal employment contracts (Argyris, 1960;

Anderson & Schalk, 1998).

Most researchers assert that psychological contracts can be interpreted as a portion of the

social exchange theory; through repeated interactions and mutual investment, social exchange

relationships come to develop implied rules of operation (Dulac et al., 2008). Others describe

psychological contracts from an integrated point of view, combining social exchange theory with

conservation of resources theory (e.g., Restubog et al., 2017; Deng et al., 2018). The primary

assertion of conservation of resources theory is that humans are motivated to acquire and protect

resources, particularly those of value to the individual (Halbesleben et al., 2014). According to

14 LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION

this line of research, psychological contract breach serves as a perceived or actual loss of

resources that may lead to employee withdrawal, harming the social exchange relationship

(Kiazad et al., 2015).

Aselage and Eisenberger (2003) argue that psychological contracts can be best

understood by integrating organizational support and social exchange perspectives. According to

this integrated perspective, perceived organizational support is tied to employee perceptions that

the organization has met obligations, or fulfills the psychological contract (Aselage &

Eisenberger, 2003). Employees reciprocate when they perceive organizational support due to the

psychological contract; the reciprocity norm in the ongoing social exchange encourages

employees to provide resources like performance in exchange for POS.

Remote work choice can be understood using a combination of the above frameworks: as

a valued resource provided by employers in the social exchange between organization and

employee, remote work choice may be governed by the reciprocity norm or psychological

contract (Lucero & Allen, 1994). By providing remote work options, organizations may

demonstrate support, provide a valued resource which employees may be motivated to keep, and

maintain the ongoing mutual investment of a social exchange (Sardeshmukh et al., 2012). In

exchange for their performance, commitment, and time, employees expect that organizations will

compensate and care for them through resource provision that may include remote work

(Levinson et al., 1962).

In navigating the decision of whether to transition back to onsite work, organizations

should consider the ways in which the transition may change perceptions of organizational

support and ultimately the social exchange relationship. Some employees may perceive remote

work as a valued resource provided in exchange for their performance, making it a key

15 LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION

component in the social exchange relationship and a vital indicator of organizational support.

Remote work choice may be perceived by some as a resource promised in a psychological

contract, an implicit agreement between employee and organization that each will provide

needed resources to the other.

Remote Work Transition as Psychological Contract Breach

For those employees who experienced remote work during COVID-19 and found it a

valuable resource, remote work choice may serve as a vital portion of the psychological co ntract

governing the ongoing exchange between organization and employee. As employees may feel

they have proven performance while working remotely, removal of remote work as a resource

may be perceived as a psychological contract breach or broken reciprocity norm (Aselage &

Eisenberger, 2003). After successfully navigating remote work during COVID-19, employees

realize that their organizations are capable of allowing remote work. Workers may recognize that

barriers to remote work previously cited by organizations are no longer present—many technical

limitations, communication difficulties, and skill gaps were addressed early in the pandemic,

making remote work increasingly possible.

The COVID-19 pandemic caused a paradigm shift in employees’ perceptions of work;

the perceived necessity of in-person work has changed in many fields, causing employees to

increasingly recognize remote work choice as a reasonable and valuable resource their

organizations can continue to provide. Organizations that remove this option, therefore, may be

seen as unwilling rather than incapable of providing a resource that employees now perceive as

fair and valuable. By forcing a universal return to office for employees, organizations may

inadvertently communicate a lack of trust, decrease in respect, or lower commitment to their

employees’ needs, creating an imbalance in contributions between employee and organization. In

16 LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION

the context of the social exchange relationship, employees may feel they have proven their

commitment to the company and upheld their portion; in removing valued resources, the

organization may be perceived as withdrawing support, breaching a psychological contract, or

breaking the reciprocity norm (Kurtessis et al., 2015).

Outcomes of Contract Breach. If employees perceive loss of remote work option as a

breach of psychological contract or broken reciprocity norm, they will likely experience negative

reactions toward the breach as well as toward the organization overall. Psychological contract

breach has been shown to cause psychological contract violation, or feelings of frustration,

betrayal, and negative affect following a perceived broken promise (Dulac et al., 2008).

Psychological contract breach and violation are also related to decreased POS; by taking away

valued resources and breaking implicit promises, organizations could decrease the perception

that they value, appreciate, and respect employees and their contributions (Kurtessis et al., 2015).

Perceived organizational support is vital to the development and maintenance of affective

commitment, or employee loyalty to the organization (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002).

Employees who perceive loss of remote work choice as a broken promise or deprivation of a

valued resource will likely perceive the organization as less supportive of their needs. By

decreasing resources provided to the employee and breaking implicit promises, organizations

may be perceived as caring less about their employees, in turn causing those employees to feel

lesser loyalty or emotional attachment to their organization (Aselage & Eisenberger, 2003). As

an indicator that employees perceive fairness in the social exchange relationship, perceived

organizational support is key in the maintenance of the ongoing relationship and provision of

employee resources like loyalty (Kurtessis et al., 2017).

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 17

If employees perceive the social exchange relationship as effectively broken and

negatively react to a psychological contract breach, they can also be expected to experience

decreased affective organizational commitment. Affective commitment, as defined by Meyer and

Allen (1991), describes an employee’s emotional attachment and identification with an

organization. As one of three types of organizational commitment posited by Meyer and Allen,

affective commitment is arguably the most important form of commitment due to its strong

relationships with outcomes such as withdrawal cognition, attendance, in-role and extra-role

performance, stress, turnover intent, and actual turnover behavior (Meyer et al., 2002). Prior

research has indicated that decreased perceptions of organizational support lead to lower

affective commitment to the organization (Kurtessis et al., 2017). As employees perceive the

organization as less supportive and the psychological contract as broken , they may feel less

loyalty or emotional attachment to the organization, leading to increased turnover intent as they

seek supportive organizations willing to provide valued resources. (Maertz et al., 2007).

In removing remote work choice, organizations may be creating a chain reaction, a

broken psychological contract which leads to negative attitudes toward the organization and

ultimately higher turnover for those employees who most value remote work. As a measure of

the reaction to psychological contract breach rather than the perception of breach itself,

psychological contract violation may play an important role in the relationship between remote

work preference and turnover intent due to its more direct relationship with other attitudes such

as POS and affective commitment. This relationship takes the form of a partial serial mediation;

the relationship between remote work preference and turnover intentions could be partially

explained by psychological contract violation leading to decreased POS, lower affective

commitment, and greater turnover intent.

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 18

Hypothesis 1. There will be a positive relationship between remote work preference and

turnover intent.

Hypothesis 2. The relationship between remote work preference and turnover intent will

be serially mediated by psychological contract violation, perceived organizational support, and

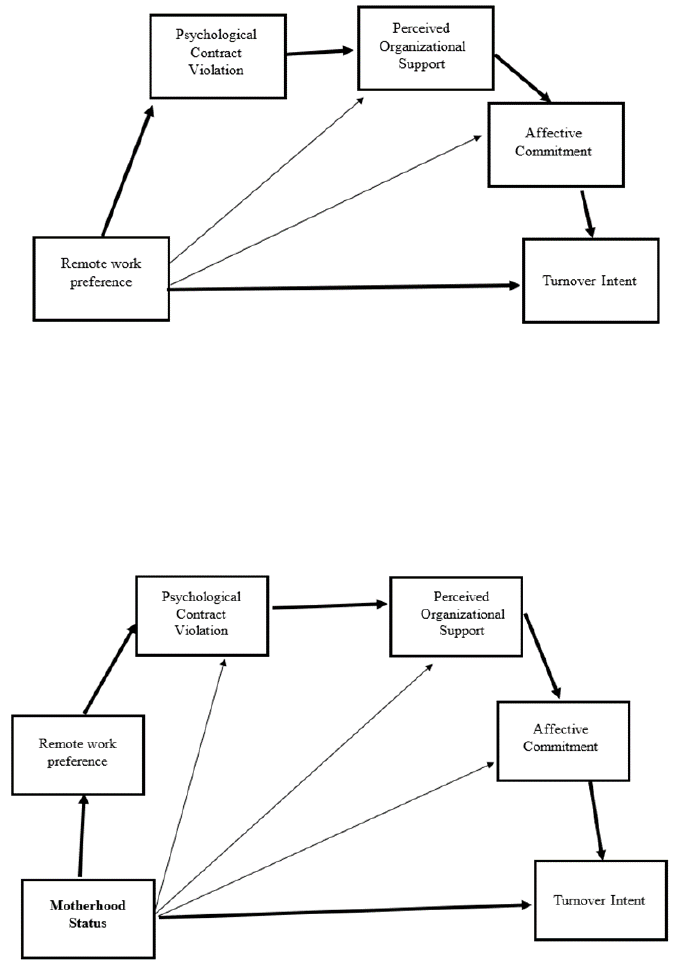

affective commitment (figure 1).

Differential Impact

By taking a blanket approach and removing remote work options for all employees,

organizations may decrease perceptions of support and break the implicit contract; for those

employees who most value remote work, the impact of this transition to onsite work may be

larger (Mitchell et al., 2012). Employees undoubtedly have developed different attitudes toward

remote work during the pandemic; for some, telework choice may be extremely valuable as a

source of needed flexibility that enhances their careers. As companies consider how best to

transition their workforce post-COVID, they should consider employee characteristics and

differing needs when determining how best to provide support and avoid attrition (Rousseau et

al., 2006). Understanding and providing resources that support individual needs will strengthen

the social exchange relationship between organization and employee, reinforcing the obligation

to reciprocate with performance and commitment (Gouldner, 1960).

Working Mothers

Among those for whom remote work may have particular value are working parents, and

especially working mothers. Mothers face unique pressures at work due to conflicting home and

career demands, gender stereotypes and societal expectations, and the historical exclusion of

mothers from the workplace (Heilman, 2012). Working mothers are expected to work as though

they do not have childcare responsibilities while also parenting as though they do not have

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 19

career-related responsibilities (Heilman, 2012). Lack of employer-provided caregiving benefits,

limited government support, and cultural norms for parents can make motherhood especially

difficult for those who choose to or need to work (Collins, 2019). The choice to work is in itself

a unique pressure for mothers: women historically face much greater pressure to choose between

career and family, while men are not expected to choose only one (Genz, 2010).

Women who resist the pressure to choose between work and family face conflicting

demands and intense time pressures. Even as women’s participation in the workforce has grown

through past decades, mothers have continued to complete a disproportionate amount of

housework and childcare (Beghini et al., 2019; Chesley & Flood, 2017; Kamo, 1998; Evertsson

& Nermo, 2007). These gender norms have been reinforced by external factors such as state

policies favoring traditional work/family arrangements (Crompton, 1999; Lewis, 2001), high

childcare expenses (Wrohlich, 2011), devaluation of traditionally female professions (England,

2010), persistent wage gaps (Kochhar et al., 2020; Matteazzi & Scherer, 2020), and normative

beliefs about motherhood (McDonald et al., 2014). Among families in which both mother and

father work full-time, mothers report spending more time on childcare than fathers, even when

mothers have greater incomes than fathers (Pew Research Center, 2015; Schneider, 2011;

Bittman et al., 2003).

Differential experiences at home can also impact women’s success and progress at work.

Traditional work systems such as 40-hour workweeks, structured daytime working hours, and

even physical work environments have largely been crafted around a theoretical “ideal wo rker”

who is stereotypically a heterosexual man and can rely on a spouse to complete all domestic

labor, allowing him to focus almost solely on career (Acker, 1990). As more women participate

in the workforce and work to climb organizational ladders, these structures continue to be

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 20

obstacles in the path of gender equality in the workplace. Men continue to make up the vast

majority of business leaders; as of 2022, just 33 S&P 500 companies were led by women CEOs,

and women made up less than one-third of senior management in U.S. organizations (Catalyst,

2022).

Women are also more likely to leave the labor force completely due to conflicting home

and work demands. Among working-age people, married women are least likely to participate in

the workforce while married men are most likely to be working (BLS, 2021). Mothers with

young children are especially likely to withdraw from the workforce, whereas men’s labor force

participation does not significantly differ as a function of dependents. Once they leave the

workforce, many mothers struggle to reenter, creating an environment where mothers are forced

to choose long-term between family and career (Weisshaar, 2018).

Previous research has shown caregiving and work-family conflict to be leading causes of

women’s departure from the workforce in early to mid career, decreasing representation among

senior management levels (Miles, 2013; Cabrera, 2009; Henderson, 2005). When forced to

choose between prioritizing work or family, many women feel societal pressures to choose

family, while men are not forced to make the same type of either-or choice (Miles, 2013). The

balance of work and family can be made more challenging by the structured timing and location

of work, which may interfere with parents’ ability to spend time with children, accommodate

family schedules, and tend to home care responsibilities (Lord, 2020).

Working Mothers’ Remote Work Preference. Remote work may play a unique role in

facilitating the balance of work and family for employed mothers. Past research has found that

women on average have a greater preference for remote work than their male colleagues; women

were also more likely to cite family responsibilities and stress reduction as primary reasons for

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 21

wanting remote work (Mokhtarian et al., 1998; Agovino, 2022). Mothers may also place greater

value on telework options due to expectations that they advance career goals while

simultaneously prioritizing family needs (Weisshaar, 2018).

The flexibility provided by remote work can help to lessen historical gender inequality in

the structure of work and home responsibilities (Acker, 1990; Lord, 2020). Remote work options

may be of greater importance to mothers who experience high demands of housework and

childcare; by providing flexibility in location as well as eliminating commute times,

organizations can help mothers to handle time pressures from home and work. Because women

complete a disproportionate amount of childcare and housework, time gained by working

remotely may be especially helpful as women seek to balance work and family (Beghini et al.,

2019). While the gap in home responsibilities may slowly close with large-scale interventions,

organizations can play an immediate role in providing women the flexibility they need to prevent

these home demands from detracting from career goals.

As mothers navigate conflicting demands from work and home responsibilities, remote

work may have the potential to help decrease career disadvantages by providing flexibility to be

both: mother and worker. Onsite work with designated hours, long commutes, and time away

from families can be particularly challenging for working mothers who feel pressure to balance

work and family responsibilities throughout the day (Lord, 2020). Previous research has

indicated that home-based workers experience lower work-family conflict, and remote work

options may allow mothers to continue career pursuits while handling home tasks like after-

school pickup, meal preparation, and caring for sick children (Sakamoto & Spinks, 2008;

Dooley, 1996). By eliminating commutes, time pressures may decrease, leaving time for home

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 22

and family responsibilities before and after the workday as well as during breaks (Peters & van

der Lippe, 2007; Aksoy et al., 2023).

If organizations hope to retain and attract mothers post-COVID, consideration of the

differential costs and benefits of telework is necessary; according to one study, mothers with

remote work options were 32% less likely to leave their jobs than mothers who were not

permitted to work remotely (Van Bommel, 2021). Given uniquely conflicting demands of work

and home, remote work choice may serve as an extraordinarily valuable resource for working

mothers, causing them to have greater preference for remote work compared with other

employees who do not face the same pressures to prioritize both work and home.

Hypothesis 3. Mothers will report greater remote work preference compared with fathers,

women without children, and men without children.

Social Exchange: Valued Resources

For working mothers, telework choice may prove to be an extra valuable resource,

providing flexibility while decreasing pressure to choose between work and home. In the

integrated views of social exchange, organizational support, and conservation of resources

theories, remote work choice can be seen as a resource provided in the social exchange that

mothers may be highly motivated to protect (Kiazad et al., 2014). Remote work options may be

perceived as a vital indicator of organizational support and respect for the unique needs of

working mothers (Gouldner, 1960). In providing this highly valued resource, organizations may

be more likely to preserve a strong social exchange relationship; working mothers in turn may

fulfill the reciprocity norm, providing strong performance and commitment in exchange for this

continued support (Restubog et al., 2017; Mitchell et al., 2012; Kelliher & Anderson, 2010).

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 23

As organizations navigate a post-COVID transition, they should assess how the resource

of telework may be valued differently by certain groups, including caregivers. If they hope to

maintain representation of women and working mothers in their organizations and prevent

attrition, they should consider individual needs and understand how providing flexibility may

promote perceptions of support and mutual investment (Rousseau et al., 2006).

Broken Reciprocity and Contract Breach. As part of the continuous exchange of

resources between organization and employee, remote work choice may be considered a

necessary portion of the social exchange relationship, particularly for mothers who have begun to

rely on the flexibility it provides. By removing remote work options for employees, the

organization may be perceived as breaking the norm of reciprocity; working mothers may feel

that they have proven loyalty and performance during the challenge of COVID-19, upholding

their obligations (Aselage & Eisenberger, 2003). By breaking this reciprocity norm,

organizations may ostracize working mothers, who may view the removal of valued remote work

choice as a broken promise to provide resources as part of the social exchange. In this way,

mothers too might perceive the loss of remote work as a psychological contract breach.

With remote work holding additional value for working mothers, negative reactions to

this contract breach are expected. Psychological contract violation, or negative affective

responses to the breach of psychological contract, may arise. Among working mothers, however,

reactions to the loss of remote work may be even stronger due to greater valuation of remote

work as a resource (Mitchell et al., 2012). If remote work proves to have greater importance for

working mothers, removal of telework options may be especially damaging to perceived

organizational support. As an indicator of the organization’s fulfillment of the social exchange,

and as a signal that organizations support working mothers, perceived organizational support is

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 24

key to the maintenance of affective commitment (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002). With

decreasing POS due to broken psychological contract, mothers can be expected to report lower

affective commitment, ultimately leading to greater turnover intent (Dulac et al., 2008; Kurtessis

et al., 2015; Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002; Aselage & Eisenberger, 2003; Maertz et al., 2007). In

this way, motherhood status can predict turnover intent in organizations removing telework

choice; mothers can be expected to report higher intent to leave the organization due to greater

remote work preference leading to psychological contract violation, lower perceived

organizational support, and lower affective commitment. As each of these attitudes are

interrelated, a partial serial mediation model best describes this relationship (Hayes, 2017; figure

2).

Hypothesis 4. Working mothers will report greater turnover intent than working fathers

and workers without children.

Hypothesis 5. The motherhood status-turnover intent relationship will be serially

mediated by remote work preference, psychological contract violation, perceived organizational

support, and affective commitment (Figure 2).

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 25

METHOD

Participants

To understand the attitudes of workers experiencing a return to onsite work, this study

focused primarily on employees who experienced remote work for a meaningful amount of time

in the past three years and who have since been required to return to onsite work. Although this

narrowed the potential sample significantly, a large proportion of knowledge workers

experienced this transition in 2021 and 2022. As of August 2021, an estimated 66% of surveyed

organizations that switched to remote work during the pandemic had announced that offices

would wait to reopen until early 2022, and twice as many Fortune 100 companies (34%) returned

to office in 2022 as did in 2021(Baker & Zuech, 2021; O’Loughlin, 2023). While proportions of

remote workers remain high compared to pre-COVID, the number of teleworkers in 2022 was

less than half of the proportion working remotely in May 2021, reinforcing that many had

experienced the transition from remote work back to office work. Throughout 2020 and 2021,

many traditionally office-based workers experienced remote work for the first time. Armed with

firsthand remote work experience, workers have undoubtedly developed attitudes toward remote

work and reactions to the expectation that they return to onsite work during or after the

pandemic, making 2022 an ideal time to assess attitudes toward this transition.

Following the guidance of Fritz and Mackinnon (2007) on required sample sizes for

detecting mediation effects, this study initially targeted 400 participants with at least 100

participants from each group: working mothers, working fathers, women without children in the

home, and men without children in the home. While larger sample sizes are often needed for

multiple mediation, historically strong effect sizes among psychological contract violation,

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 26

perceived organizational support, affective commitment, and turnover intentions made a targeted

minimum sample of 400 possible.

Participants in this study were U.S.-based workers who had experienced remote work and

since transitioned back to onsite work. To capture attitudes about loss of remote work, subjects

were limited to those who had worked remotely for their current employer for at least three

months in the past two years and who had since been required to return to onsite work for at least

50% of their working hours. Due to the relevance of childcare demands for this study, only those

working 20 hours per week or more at their primary job were included in the study. Participants

were screened for remote work experience, the expectation that they returned to onsite work for

at least half of working hours, and parenthood status to ensure adequate representation of parents

and non-parents; to qualify as a working parent, subjects must have had one or more children

under the age of 18 living in their home with them.

Subjects were obtained via snowball sampling in order to capture responses from workers

both with and without children who have experienced remote work and return to onsite work

across multiple industries. Recruitment messages were shared via social media, email, working

parents’ support groups, organizational contacts, and working MBA students in order to capture

a wider assortment of workers.

Sample

Over the course of 9 months of snowball sampling in 2022, a total of 2662 potential

participants attempted to take the survey; after screening based on the above requirements, 1200

participants completed the survey. Of these 1200, 67 participants were excluded for failing

attention checks and 63 were excluded for spending less than four minutes completing the

survey. This resulted in a final sample of qualifying responses of 1070. 56.1% of participants

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 27

were women, while 43.6% were men; both snowball sampling and gender differences in

willingness to participate may have influenced this over-representation of women (Groves et al.,

1992). Among the qualifying sample were 451 working mothers, 149 women without children,

377 working fathers, and 89 men without children. An additional 4 respondents selected “prefer

not to answer” when asked their gender and were excluded from gender and parent-type

analyses. While the proportion of working parents is high, targeted sampling of working parents

through support groups may partially explain their disproportionate representation.

Among qualifying participants, 68.9% were white, 15.4% Black or African American,

8.5% Asian American, 6.9% Hispanic or Latino, and 1.3% were other. Participants could select

one or multiple races and/or ethnicities. While this sample mirrors overall representation in the

U.S. labor force relatively well, some over-sampling of Black participants and under-sampling of

Hispanic/Latino participants occurred, likely due to both snowball sampling and screening

requirements. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Hispanic and Latino workers have been

disproportionately represented among “essential workers” in fields that cannot participate in

remote work, likely leading to lower representation in a sample requiring remote work

experience (Schnake-Mahl et al., 2021).

Participants were also asked to report household income; among qualifying participants,

4% reported a household income less than $20,000, 2.5% reported income of $20,000 -$34,999,

4.4% reported income of $35,000-$49,999, 19.2% reported income of $50,000-$74,999, 22.4%

reported income of $75,000-$99,999, 21.4% reported income of $100,000-$124,999, 19.4%

reported income of $125,000-$149,999, and 10.3% reported income over $150,000.

While participants were screened for the requirement that they had been required to

return to onsite work at least 50% of their work time, they were also asked how much of their

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 28

work time they were working onsite at the time of the study. Among qualifying participants,

10.5% were working onsite 0-24% of their work time, 45.2% were onsite 25-49% of their work

time, 25.1% were onsite 50-74% of their work time, and 19.3% were onsite 75-100% of their

work time. Over half of participants who had been required to return to onsite work at least for at

least 50% of work hours were no longer working in-person at least half-time at the time they

took the survey, despite a requirement that they remain employed by the same employer that

required the return to site. This unexpected finding indicates that, even among organizations

requiring a return to onsite work, many may have adjusted expectations or compromised with

employees and no longer require in-person work to be 50% or greater after the initial transition

back.

Procedure

Following completion of consent form, subjects answered a one-time online survey

containing the scales below (Appendix A). This study utilized a cross-sectional approach to

avoid context effects such as new organizational announcements that may otherwise happen

between survey completions in a longitudinal study. To limit demand effects in this cross-

sectional survey, remote work and psychological contract scales were presented last.

Recruitment messages stated that the purpose of the survey is to better understand employee

attitudes toward work during the pandemic without specifically mentioning psychological

contract breach or attitudes toward loss of remote work. The survey took approximately ten

minutes and included multiple attention checks to detect careless responding. Participants who

incorrectly answered any attention check were excluded from analysis.

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 29

Measures

Remote Work Preference. Temporal preference for remote work was asked using the

item “In a typical 5-day workweek, how many days would you prefer to work remotely?” with

answers from 0-5 days remotely. Attitudinal preference for onsite work was captured using an

adapted form of Nicholas and Guzman’s Attitudes toward Teleworking scale (α=.90), with items

including “In-person is my preferred method of work,” “The opportunity to work onsite is

important to me,” and “I prefer organizations that offer in-person work.” Participants indicated

agreement on a 5-point Likert-type scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

Self-Rated Performance. Because the social exchange relationship between

organization and employee relies upon perceived contributions from both, participants rated their

own performance throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Self-rated performance was assessed

using Williams and Anderson’s (1991) in-role performance scale adapted to reflect previous

rather than current performance (α=.91). Subjects were asked to assess their own performance

during the COVID-19 pandemic by indicating their agreement with questions like “I have met

formal performance requirements of the job,” and “I adequately completed assigned duties.”

Participants indicated agreement with each item on a 5-point Likert-type scale from strongly

disagree to strongly agree.

Perceived Organizational Support. Subjects were asked about their perceptions that

their organization actively supports them using Eisenberger and colleagues’ 2001 POS scale

(α=.83). Items include “My organization takes pride in my accomplishments,” and “My

organization strongly considers my goals and values.” Participants indicated agreement with

each item on a 5-point Likert-type scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 30

Social Exchange Relationship. The extent to which participants view their relationship

with their organization as part of a social exchange was assessed using Colquitt and colleagues’

2014 measure of social exchange relationships (α=.91). Participants were asked to indicate

whether the terms provided accurately describe their relationship with their organization. The

primary prompt is “My relationship with my organization is characterized by:” and items include

“Mutual obligation,” “Mutual trust,” “Mutual commitment,” and “Mutual significance.”

Participants indicated agreement with each item on a 5-point Likert-type scale from strongly

disagree to strongly agree.

Psychological Contract Breach. Perceived breach of psychological contract by the

employer was asked using a version of Robinson and Morrison’s (2000) scale (α=.97), adapted

to address remote work specifically. Items include “I feel that my employer has come through in

fulfilling the promises made to me [about remote work],” (reverse coded) and “My employer has

broken many of its promises to me [about remote work] even though I’ve upheld my side of the

deal.” Subjects indicated agreement on a 5-point Likert-type scale from strongly disagree to

strongly agree.

Psychological Contract Violation. Affective responses to psychological contract breach

were asked using a version of Robinson and Morrison’s (2000) contract violation scale (α=.96),

adapted to address psychological contracts with the organization rather than with one supervisor.

Items include “I feel a great deal of anger toward my organization,” and “I feel betrayed by my

organization.” Subjects indicated agreement on a 5-point Likert-type scale from strongly

disagree to strongly agree.

Organizational Commitment. Affective commitment, or positive emotional attachment

to the organization, was the primary focus of commitment items due to its greater predictive

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 31

power for attitudinal and behavioral outcomes (McGee & Ford, 1987). Allen and Meyer’s (1990)

measure of affective commitment was presented (α=.87); participants rated agreement from 0-5

on measures such as “I do not feel emotionally attached to this organization,” [reverse coded]

and “This organization has a great deal of personal meaning for me.”

Turnover Intent. Intentions to leave the organization were asked using Seashore et al.’s

(1982) turnover intent scale (α=.95). Example items include “I often question whether to stay at

my current job,” and “I am looking for a change from my current job.” Subjects indicated

agreement on a 5-point Likert-type scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

Personal and Family Demographics. Participants were asked demographics including

gender and race/ethnicity as well as other family characteristics such as household income,

number of children living in the home, and marital status. While participant screening questions

were asked first, other demographics were asked near the end of the survey to avoid undue

influence or priming of subjects.

Analyses

Relationships between remote work preference, mediators, and turnover intentions were

first calculated using Pearson correlations. Preferences for remote work and differences in

turnover intent by parenthood status and gender (i.e., mothers, fathers, men a nd women without

children in the home) were then analyzed using ANOVA with post-hoc, Tukey’s HSD test for

multiple comparisons with Bonferroni correction. Direct and indirect effects of remote work

preference and motherhood status on turnover intent were calculated in regression-based serial

mediation analyses for each of the two models using the PROCESS macro for SPSS (model 6

with three and four mediators respectively; Hayes, 2017). To assess for significance of indirect

effects, a bootstrapping technique was utilized to calculate 95% confidence intervals. For the

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 32

motherhood status-turnover intent serial mediation model, motherhood status was grouped into

mothers and non-mothers (including fathers and participants without children), with 1 indicating

a mother and 0 indicating a non-mother.

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 33

RESULTS

Preliminary Results

Means, standard deviations, and correlations between each of the study’s variables are

presented in Table 1 (Appendix B).

Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis 1 predicts that there will be a positive relationship between remote work

preference and turnover intentions. As predicted, temporal remote work preference, or a

preference for a greater number of days working remotely each week, was positively correlated

with turnover intent (r(1068) = .22, p < .001). When preference for onsite work was measured

attitudinally, there was a negative relationship with turnover intent (r(1068) = -.29, p < .001.),

further supporting hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 2 predicts that the relationship between remote work preference and turnover

intent will be serially mediated by psychological contract violation, perceived organizational

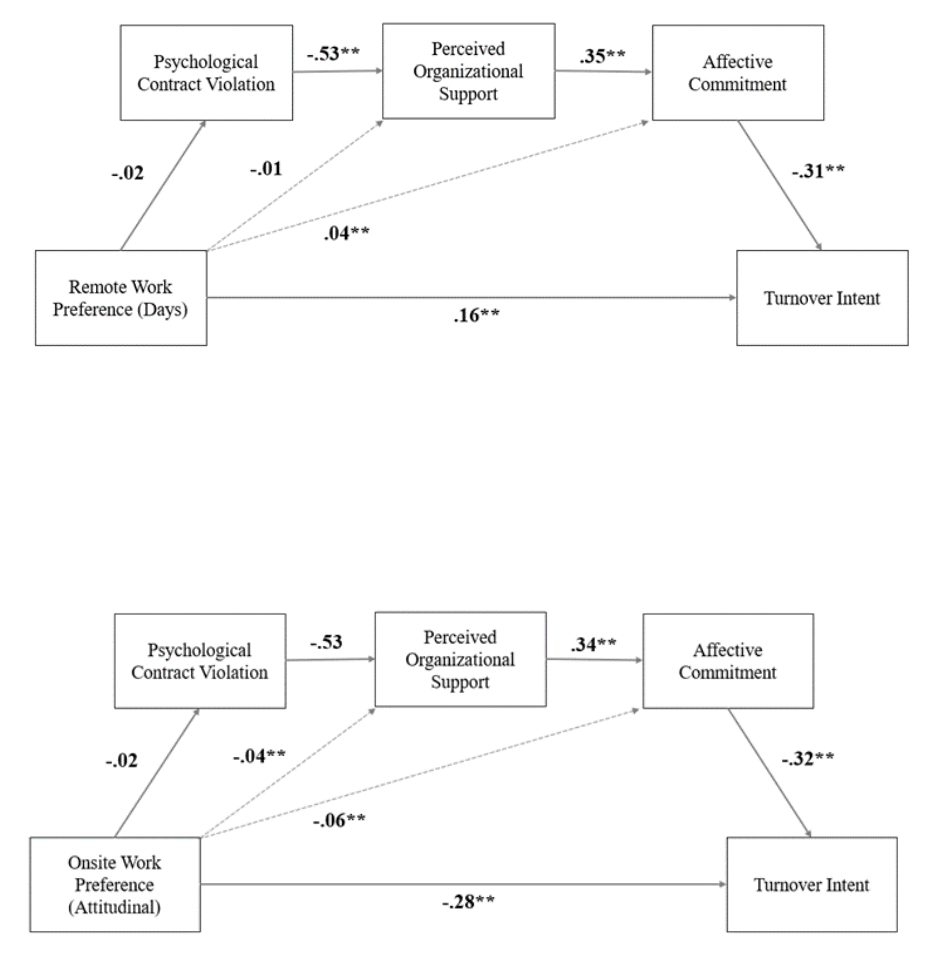

support, and affective commitment (figure 1). Direct and indirect effects of both temporal remote

work preference and attitudinal onsite work preference were calculated in a regression-based

serial mediation. There was no significant indirect effect of remote work preference on turnover

intent through psychological contract violation, POS, and affective commitment (b = -.001, t =

.90, 95% CI [-.003, .001], figure 3; Appendix C), failing to support hypothesis 2. An alternative

indirect effect, however, was statistically significant, indicating that affective commitment

mediates the relationship between temporal remote work preference and turnover intent (b = -

.01, t = -2.85, 95% CI [ -.02, -.005]). There was also a direct effect of remote work preference on

turnover intent (b = .16, t = 9.22, p < .001), indicating a partial mediation through affective

commitment.

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 34

Similarly, there was no significant indirect effect of attitudinal onsite work preference on

turnover intent through psychological contract violation, POS, and affective commitment (b = -

.001, t = .81, 95% CI [-.01, .002]; figure 4), also failing to support hypothesis 2. An alternative

indirect effect, however, was statistically significant, indicating that perceived organizational

support and affective commitment partially mediate the relationship between attitudinal onsite

work preference and turnover intent (b = .005, t = 2.09, 95% CI [.001, .01]). There was a direct

effect of onsite work preference on turnover intent (b = -.28, t = -11.08, p < .001), indicating

only partial mediation through POS and affective commitment.

Hypothesis 3 predicts that mothers would report greater preference for remote work

compared with fathers, women without children, and men without children. A one-way ANOVA

revealed a significant difference in preference for days working remotely between at least two

groups (F(4, 1065) = 13.79, p <.001). Tukey’s HSD Test for multiple comparisons showed that

the mean value of temporal remote work preference was significantly greater for women with

children (M = 2.95, SD = 1.32) compared with men without children (M = 2.48, SD = 1.61; p =

.03; d = .32), women without children (M = 2.33, SD = 1.56; p < .001; d = .43) and men with

children (M = 2.28, SD = 1.32; p < .001; d = .51), supporting hypothesis 3.

When tested with attitudinal preference for onsite work, a similar pattern emerged; a one-

way ANOVA revealed a significant difference in attitudinal preference for onsite work between

at least two of the groups (F(4, 1065) = 30.73, p < .001). Tukey’s HSD Test for multiple

comparisons showed that the mean value of onsite work preference was significantly lower for

women with children (M = 3.07, SD = .98) compared with men without children (M = 3.65, SD =

.97; p < .001; d = .59), women without children (M = 3.43, SD = 1.13; p < .001; d = .34), and

men with children (M = 3.75, SD = .67; p < .001; d = .81), also supporting hypothesis 3.

LOSS OF REMOTE WORK AS PSYCH. CONTRACT VIOLATION 35

Hypothesis 4 predicts that mothers would report greater turnover intent than fathers,

women without children, and men without children. A one-way ANOVA revealed that there was

a significant difference in turnover intent between at least two of the groups (F(4, 1065) = 8.90, p

<.001). Tukey’s HSD test for multiple comparisons found that women with children reported

significantly greater turnover intent (M = 2.49, SD = .85) only when compared with men with

children (M = 2.15, SD = .71; p < .001; d = .43) but not when compared with men without

children (M = 2.30, SD = 1.11; p = .38, d = .19) nor women without children (M = 2.54, SD =

1.31; p = .99, d = .05), partially supporting hypothesis 4.

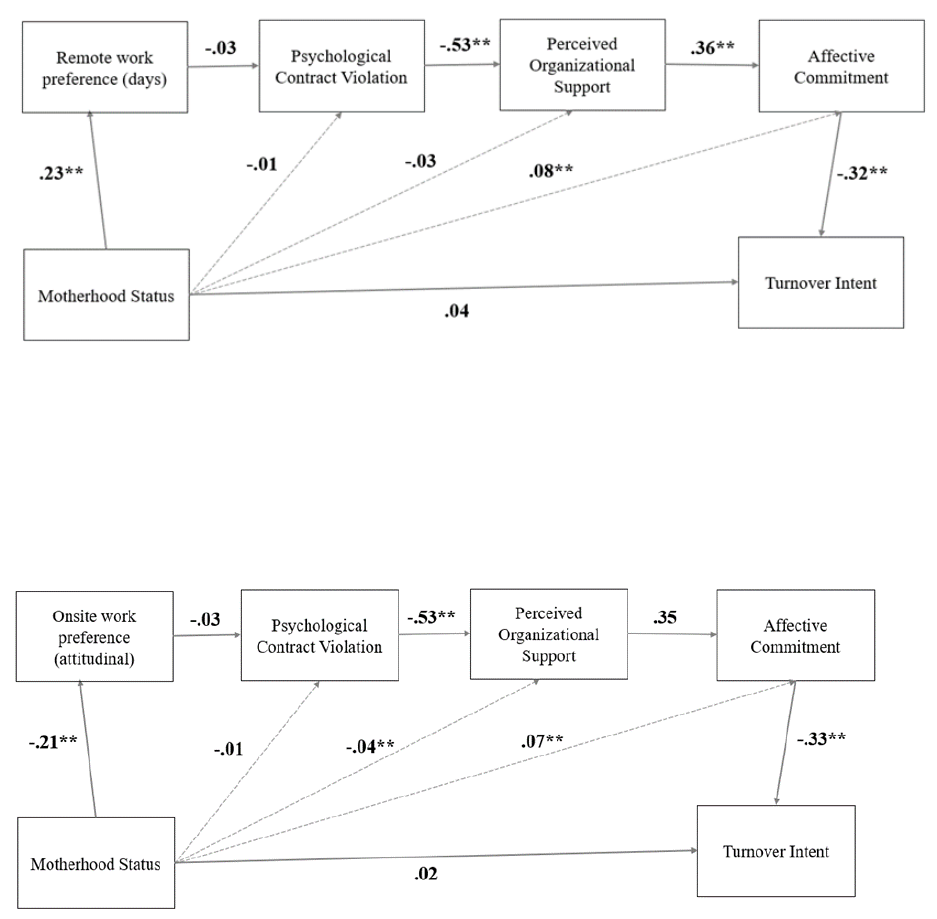

Hypothesis 5 predicts that the motherhood status-turnover relationship will be serially

mediated by remote work preference, psychological contract violation, perceived organizational

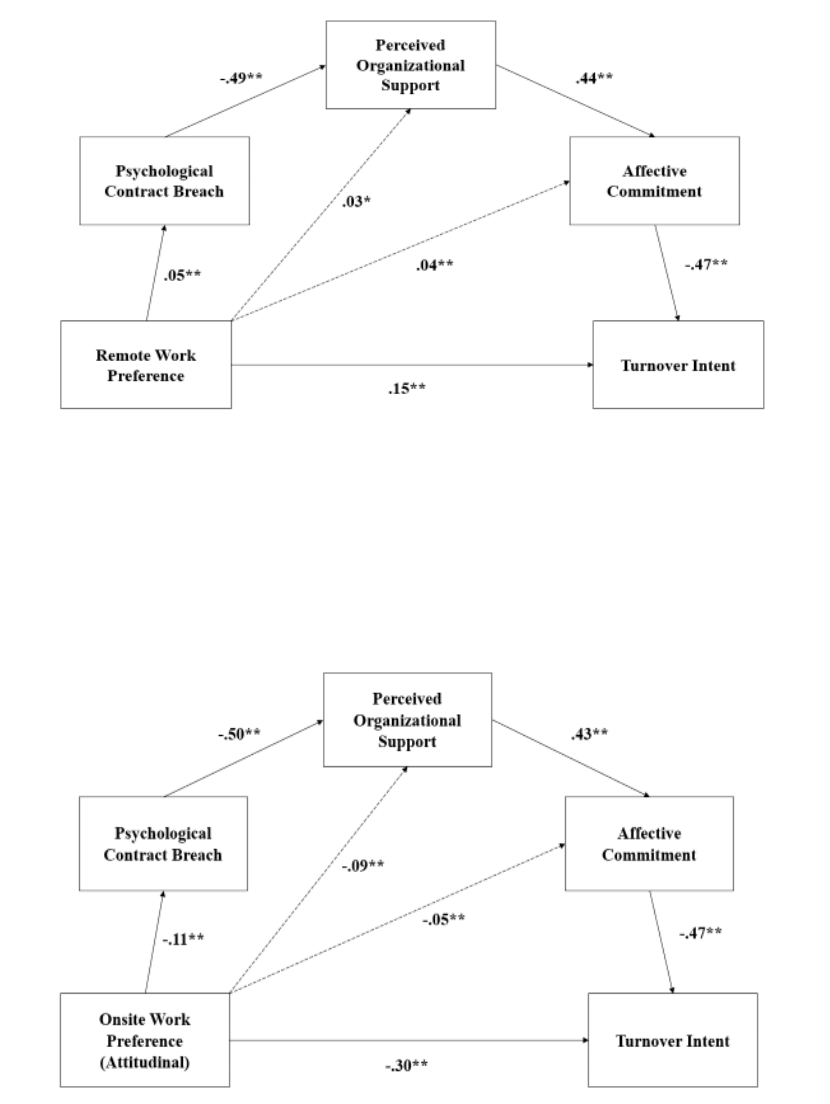

support, and affective commitment. There was no significant indirect effect of motherhood status