is is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.

org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author

and source are credited.

Copyright © 2022 e Author(s). Published by Vilnius Gediminas Technical University

DEMOGRAPHIC DIFFERENCES MATTER ON JOB OUTCOMES:

PSYCHOLOGICAL CONTRACT’S MEDIATING ROLE

Ali Ender ALTUNOĞLU

1*

, Özge KOCAKULA

2

, Ayşe ÖZER

3

1

Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, Muğla Sıtkı Koçman University, Muğla, Turkey

2

Management and Organization Department, Aydın Adnan Menderes University, Aydın, Turkey

3

Department of International Relations and Trade, Muğla Sıtkı Koçman University, Muğla, Turkey

Received 08 May 2021; accepted 07 January 2022

Abstract. Purpose – Drawing upon prior researches on the social exchange theory, we examine the

eect of employee demographic variables on psychological contract fulllment, which eventually

inuences employee’s job satisfaction, intention to leave, organizational citizenship behavior, cyni-

cism, and task performance.

Research methodology – Data from 274 employees of dierent manufacturing enterprises has been

collected through the survey. Description and interpretation statistics are used through SPSS and

also AMOS. Structural equality modeling is used to assess the psychological contract’s mediating

function.

Findings – Data analysis shows that psychological contract fulllment mediated positive relation-

ships between demographic variables and constructive job outcomes; in contrast, mediated negative

relationships between demographic variables and destructive job outcomes.

Research limitations – is paper applies data from the manufacturing industry operating in Turkey,

which may prevent the generalizability of the paper. More study is needed to conrm these results

on dierent samples in order to generalize ndings. In addition, the data comes from a single source,

raising the risk of common technique bias, and is focused solely on self-reports.

Practical implications – e study suggests that organizations review and revise their ideas on the

exchange connection with their workforce as job outcomes of employees are connected to PC ful-

llment. In practice, managers and leaders may highlight that such fulllment constitutes an in-

vestment of resources into and a long-term commitment to the employee in addition to satisfying

relational responsibilities. Leaders should place a strong emphasis on increasing employee com-

mitment levels. Creating a culture of trust and loyalty fosters benecial behavioral and attitudinal

results among employees.

Originality/Value – is study investigated psychological contract fullment’s mediator eect on the

relationship between demographic dierences and job outcomes.

Keywords: demographic variables, job outcomes, psychological contract fulllment.

JEL Classication: J21, J23, J24.

Business, Management and Economics Engineering

ISSN: 2669-2481 / eISSN: 2669-249X

2022 Volume 20 Issue 1: 1–22

https://doi.org/10.3846/bmee.2022.14895

*Corresponding author. E-mail: aealtunogl[email protected]u.tr

2

A. E. Altunoğlu et al. Demographic dierences matter on job outcomes: psychological contract’s...

Introduction

Unlike service, manufacturing companies pay more attention to issues such as produc-

tion, quality, and safety. Other critical success factors like employee attitudes are generally

neglected (Michael et al., 2005). However, enhancing workplace attitudes and behaviors

are general and costly problems within their organization in the manufacturing sector (Lee

et al., 2006). e literature on organizational behavior covers a wide variety of attitudes

and behaviors. Drawing on the framework employed by Robinson (1996), this research

investigates ve job outcomes considered as crucial for organizational success. is study

intends to focus on job satisfaction, intention to leave, organizational citizenship behavior

(OCB), cynicism, and task performance. While OCB, task performance, and job satisfac-

tion are considered positive and constructive, intention to leave and cynicism are consid-

ered harmful and destructive. ese outcomes are interrelated and mutually aect each

other. erefore, it seems necessary to examine the association between these workplace

attitudes and behaviors and their antecedents to provide an insight into the eectiveness of

manufacturing companies. Hence, the underlying objective of this study is to examine the

strike demographic variables with organizational outcomes such as intention to leave, job

satisfaction, OCB, cynicism, and task performance through psychological contract fulll-

ment (PCF). Failure to form an employee’s psychological contract (PC) will make it dif-

cult for the organization to reduce motivation and performance, prevent organizational

engagement, job satisfaction, and OCB, which is regarded as extremely important for the

organization, will not be fully formed (Vos et al., 2005). In order to avoid destructive out-

comes such as these, the concept of PC should be handled consciously. In this sense, PCs

are regarded as one of the practice areas to examine employer and employee relations with

changing management approaches.

e rst objective is to analyze the connection between demographic factors with PCF

and workplace outcomes. Demographic factors seem and aecting factors of outcomes. is

study investigates any relation between job attitudes and gender, age, education level, tenure,

and occupational level in light of prior research. Possible results will support organizations

in their eorts to enhance the level of employee job outcomes.

e research’s second objective is to assess the link between PCF and workplace out-

comes. Rousseau (1995) argues that a PC exists when an unwritten belief between the worker

and the manager about the parties’ conditions and expectations. e common point of all

reviews is a trade-o between employers and employees concerning the PC. e PC involves

monetary obligations and exchanging socio-emotional elements (job satisfaction, cynicism,

etc.). In this sense, the PC principle is founded on the employee’s reaction in the face of the

employer’s behavior (Coyle-Shapiro & Kessler, 2002). erefore, social exchange theory may

be utilized to analyze the act of PCs upon employees’ approaches and actions. Given the sig-

nicance of PCing, this research’s general goal is to explain the organizational consequences

of strengthening workplace attitudes and behaviors within their organization.

e study’s nal goal is to display the mediating eect of PCF in the eect of demographic

variables on destructive and constructive employee work attitudes. In addition, this research

will expand the evolving empirical studies on PCF by examining PCF as a mediating variable.

Business, Management and Economics Engineering, 2022, 20(1): 1–22

3

is study is designed as follows to achieve these objectives. e rst part covers demo-

graphic factors and their possible associations with job attitudes and the PC. e following

section examines PC and focused constructive and destructive work attitudes and highlights

the advantages of higher job outcomes for organizations. ese are traced by an analysis of

the relationship between the PCF with those job attitudes. e discussion will be noted us-

ing the survey method to gather data and measurement details for each variable. Finally, the

conclusions, limitations and future directions of studies are outlined aer evidence of results.

1. eory

1.1. Demographic dierences

Rousseau (1995) goes beyond looking at exchanges between workers and managers and

states the necessity to consider demographic dierences since employees perceive contrac-

tual psychological conditions based on their dierent motivations and attitudes. erefore,

demographic factors are considered crucial impact factors of job attitudes. e study explores

any connection between job attitudes, PCF and gender, level of education, age, tenure, and

occupational level given prior studies.

Gender is one of the widely discussed individual dierences in the literature. Gender is

a socially created role, attitudes, habits, and traits that a particular culture assumes are ap-

propriate for males and females (Bem, 1981). Gender can aect employee expectations from

work and his/her job outcomes (Bal et al., 2008). Prior studies indicate distinctions between

the PCF and gender job attitudes (Hoque, 1999; Abela & Debono, 2019). Work-family con-

ict can occur, especially for women, when working in a male-dominated value system such

as manufacturing. Sustaining employee job outcomes, especially women, is a challenge for

today’s businesses. ese disputes can cause unhappiness and distress in the workplace and

family, leading the female to eventually leave (Netemeyer et al., 1996; Callister, 2006). Ac-

cording to researchers, women face more disputes than men (Hammer et al., 1997). ere-

fore, the psychological agreement between males and females may vary. Moreover, gender

dierences have been linked to job satisfaction (A. Sousa-Poza & A. A. Sousa-Poza, 2003;

Netemeyer et al., 1996), intent to leave (Du Plooy & Roodt, 2013), OCB (Kidder, 2002), cyni-

cism (Sak, 2018), and task performance (Mackey et al., 2019).

Age emerges as an individual dierence that impacts the perceptual dierences of the

employees’ motivations and attracts researchers’ attention. Age dierences have been as-

sociated with PCF (Hess & Jepsen, 2009), job satisfaction (Kollmann et al., 2020), intent to

leave (Al Zamel et al., 2020), OCB (Ng et al., 2016), cynicism (Chiaburu et al., 2013), task

performance (Gajewski et al., 2020).

Consistent with this study, an employee’s degree of education may inuence his or her

work expectations and attitudes. Even though the ndings are mixed, there is a need to as-

sess the impacts of demographic variables like education level. It has been related to the PC

(Janssens et al., 2003). Besides, education level has been linked to job satisfaction (Knights

& Kennedy, 2005), intent to leave (Lu et al., 2002), OCB (Williams & Shiaw, 1999), cynicism

(Arabacı, 2010) and task performance (Anseel et al., 2009).

4

A. E. Altunoğlu et al. Demographic dierences matter on job outcomes: psychological contract’s...

is study argues that tenure can aect employee expectations from work and his/her

job outcomes. In their study examining dyadic relations, Ferris et al. (2009) stated that the

time spent together is crucial for determining work relationships. e importance of time in

relational PCs is addressed in the literature. Parties’ psychological agreements include mutual

respect and trust, as well as ongoing reciprocation and the sharing of intangible structures

over a prolonged period (Rousseau, 1995). When trying to get an idea of the relationship in

its early stages, the parties may make false inferences. e parties evaluate these implications

and become more precise over time (Conway & CoyleShapiro, 2012). Moreover, tenure has

been linked to job satisfaction (Castellacci & Viñas-Bardolet, 2020), intent to leave (Lall et al.,

2020), OCB (Ng & Feidman, 2011), cynicism (Chiaburu et al., 2013), and task performance

(Sturman, 2003).

In this study, blue-collar and white-collar workers were considered as occupational cat-

egories in manufacturing organizations. e PC has also been associated with occupational

categorization (Janssens et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2019), job satisfaction (Hu et al., 2010),

intent to leave (Baruch et al., 2016), OCB (Ersoy et al., 2011), cynicism (Van Hootegem

et al., 2021), and task performance (Koopmans, 2014). In the light of discussions above, the

hypotheses are developed as:

H1: ere is an interaction between demographic variables and job attitudes.

H1a: Male workers are likely to act more constructive job attitudes (job satisfaction, OCB,

task performance) and less destructive job attitudes (intent to leave, cynicism).

H1b: While there is a positive correlation between higher age and constructive job atti-

tudes (job satisfaction, OCB, task performance), there is a negative correlation with destruc-

tive job attitudes (intent to leave, cynicism).

H1c: While there is a positive correlation between a higher level of education and con-

structive job attitudes (job satisfaction, OCB, task performance), there is a negative correla-

tion with destructive job attitudes (intent to leave, cynicism).

H1d: While there is a positive correlation between high tenure and constructive job at-

titudes (job satisfaction, OCB, task performance), there is a negative correlation with destruc-

tive job attitudes (intent to leave, cynicism).

H1e: While there is a positive correlation between higher status and constructive job

attitudes (job satisfaction, OCB, task performance), there is a negative correlation with de-

structive job attitudes (intent to leave, cynicism).

1.2. Psychological contract fullment

e PC comprises the responsibilities that an employee assumes his/her organization is in

debt to him/her and the responsibilities the employee assumes he/she is in debt to his/her

organization reciprocally. As a result, social exchange theory may be used to explain the idea

of the PC and its sources and eects. According to social exchange theory, individuals shape

exchange relationships based on their interactions with others (Blau, 1986). erefore, using

the theory makes it possible to have a specic framework for explaining how workers react

if they feel their PCs are fullled.

e psychological agreement oers a chance to explore the employment relationship pro-

cedures and content by focusing on specic agreements. e PC is mainly concerned with

Business, Management and Economics Engineering, 2022, 20(1): 1–22

5

the individual employee-employer relationship. According to Rousseau (1995), individuals

may have psychological agreements, but organizations may not. e mainstream PC research

typically analyses from the individual worker’s perspective. Looking at PC through the em-

ployer’s lens has a potential problem. e validity, feasibility and usefulness of an employer’s

view on the PC have been criticized (Guest, 1998). In this study, the employee perspective

is used as a basis for exploring the employment relationship, incorporating both employer

and employee perspectives.

PC studies are generally designed to determine the consequences that employees’ sense

less than they are assured. On the other hand, employee attitudes can be aected by the

company’s fulllment of commitments (Turnley et al., 2003). Lambert et al. (2003) argue

that results are more closely linked to fullling PCs than to agreements in general. is study

utilizes a metric of PCF that enables to cover a wide variety of potential replies for the items

of the PC examined here. In the employee-organization relationship, a fullled PC provides

a sense of control and security.

e antecedents of psychological contracting are less known, particularly comparing the

types of workers within the PC regarding their exchange. Even though many factors that

aect PC, such as trust, organizational culture and leadership style, are explored in the lit-

erature, how individual factors shape PC is not adequately discussed. As a research subject,

this study evaluated demographic characteristics that shape individual behaviors -gender,

age, education, duration of employment, and position level. ese associations are already

discussed in the previous section.

H2: ere is an interaction between PCF and gender (H2a), age (H2b), education level

(H2c), tenure (H2d) and title (H2e).

1.3. Psychological contract fulllment and job outcomes

Many studies have concentrated on assessing psychological agreements and their impact

on employee outcomes. According to research, employee satisfaction is inuenced by the

violation or fulllment of PCs (Zhao et al., 2007). Looking at the current denitions of the

term “job satisfaction”, it is seen that the common idea is the satisfaction of an employee

with the job (McDonald & Makin, 2000). According to Robinson et al. (1994), a breach

of PC strongly inuences relational obligations and those employees are less motivated to

fulll their work-related obligations. Larwood et al. (1998) noted that increased PCF and

higher work satisfaction are related. e rst reason for such a statement is the gap leading

to dissatisfaction between expected and received. Secondly, employer promises but fails to

provide can oen be those dimensions of employee’ crucial job satisfaction sources (Rob-

inson & Rousseau, 1994). By fullling the promised attempts and appeals, an individual

is likely to reciprocate by fullling the commitments, establishing a good connection that

both sides would satisfy.

Employee intention to leave seems to be a crucial issue for manufacturing rms since it

determines hiring policies. Because the le might need a long time of planning for the action

(Acker, 2004), intent to leave is one of the essential components in quitting the job. Intent

to leave is a dimension of employees’ destructive perceptions toward their work. Factors re-

lated to employees’ intention to leave their employers include economic, organizational and

6

A. E. Altunoğlu et al. Demographic dierences matter on job outcomes: psychological contract’s...

personal living conditional reasons (Cotton & Tuttle, 1986). ese reasons may trigger each

other in the process, causing the intention to leave to turn into quitting behavior. Chiang

et al. (2012) stated a strong link between intention to leave and violation of the PC. e PC

binds the parties. Both parties are supposed to benet from the relationship (Robinson &

Rousseau, 1994). Even if an employee feels his or her employer be attentive and cheerful,

and even if he or she nds leaving the company to be a low cost and high prot, he or she

can still respond to the organization with commitment and to accept as a caring and positive

environment (Chi & Chen, 2007). It may be claimed that an employee’s perception of PCF

demonstrates that the employer exposes reinforcement and caring. erefore, fulllments

strengthen the tie. e employee may gain trust in the advantages of remaining in the relation

and, as a result, is less likely to leave. However, if one of the sides fails to meet their commit-

ments, this leads to a reduced intention to preserve the relationship.

OCB is expressed as an additional role behavior that is not clearly stated in the orga-

nization’s reward system, which increases the eectiveness of the employee’s organization

(Organ, 1988). Moreover, Organ described organizational citizenship as “a readiness to con-

tribute beyond literal contractual obligations” (1988, p. 22). Hence, the denition provides

that OCB is relative to a formal employee-employer contract. Besides, OCB is consistent with

the employee-employer exchange relationship. As noted earlier, Social Exchange theory is the

critical concept in the literature on employee-employer contracts. Furthermore, the PC litera-

ture states that employees will adapt their actions to their views about employment contract

(Rousseau, 1995). Consequently, it seems reasonable to expect that employees’ perceptions of

how well their company has met its obligations would aect their OCB within the company

(Robinson & Morrison, 1995).

Cynicism is dened as the way of thinking that individuals who believe that individuals

are only observing their interests and who accept everyone as enthusiastic are called “cynical”

(James, 2005). e concept of cynicism is based on dissatisfaction and anger resulting from

the employee’s doubts and frustration towards the organization, resulting in the employee’s

emotional leave from the organization. e violation of the PC, according to the research, is

one of the signicant reasons generating cynicism (Johnson & O’leary-Kelly, 2003; Anders-

son, 1996).

Task performance can be expressed as an indicator of employee productivity level in its

simplest form. Task performance shows the main tasks and responsibilities related to the job,

revealing the dierences between the jobs (Jawahar & Carr, 2007). Empirical results indi-

cate that employees maintain their balance by matching the positive contributions receiving

from the organization to their eectiveness (Rosen et al., 2009; Conway & CoyleShapiro,

2012). As a result of this interaction, a connection can be mentioned between PCF and task

performance.

H3: A fullled PC will relate positively to job satisfaction (H3a), OCB (H3b), task perfor-

mance (H3c) but negatively to cynicism (H3d) and intention to leave (H3e).

1.4. e mediating role of psychological contract fulllment

First of all, this research expects that individual dierences will result in a diverse PC as-

sessment, which will result in more favorable reactions to the constructive and destructive

Business, Management and Economics Engineering, 2022, 20(1): 1–22

7

work outcomes. PCF is anticipated to be a mediating variable that helps to clarify why

demographic variables can be linked to attitudes and behaviors. Some studies revealed that

PCs are strongly connected to employee loyalty, job attitudes, trust and turnover intentions

(Robinson & Morrison, 1995; Robinson, 1996; Johnson & O’Leary-Kelly, 2003; Turnley

et al., 2003).

e perspective of PC is shaped by individual dierences and signicantly impacts the

actions of employees. erefore, PCs can be seen as a mediating factor between individual

dierences and the outcomes of employees. Employees will generate their perceptions based

on the organization’s actions, which will determine their role in reciprocating their organiza-

tions (Wayne et al., 1997). As discussed previously, individual dierences are likely to aect

the perceptions and expectations of employees about the organizational commitments and

responsibilities underlying the employment relationships.

Demographic dierences may generate distinct perceptions of organizations making

commitments. For example, if individuals consider their organization to be considerate and

support their requirements, provide opportunities for safety and development in the work-

place, they may create an obligation to reciprocate the organization with enhanced emotional

bonds. e relationship between demographic variables and worker role behaviors might be

mediated by employees’ comprehensions of replacing the contract between themselves and

their employers. For instance, it seems fair to accept that older employee possibly experiences

lower PCF levels, resulting in lower job satisfaction since age is considered an eecting factor

on the perceptual dierences of the employees’ motivations.

e negative or positive emotions are associated with PCF. Demographic dierences that

form the social exchange expectations of employees can be attributed to higher PCF percep-

tions of employees, and then employees are more willing to exercise job outcomes. Based

on these reasons and the assumptions mentioned above, this research proposes that PCF

mediate between demographic variables and work outcomes.

H4a: PC fulllment plays a mediating role in the eect of demographic variables on

constructive job outcomes.

H4b: PC fulllment plays a mediating role in the eect of demographic variables on

destructive job outcomes.

1.5. Conceptual link

Undoubtedly, the importance of leadership styles and employee motivation in the emergence

of PC and organizational citizenship behaviors cannot be underestimated (Khan et al., 2020).

ey further argue that organizational culture and organizational citizenship behavior play a

crucial role in mediating and moderating leadership, social interaction, and leader-member

interchange theories in predicting work behavior. Leadership is signicantly connected to

individual and group organizational citizenship behaviors (Euwema et al., 2017). Besides, the

literature suggests that employees’ PCs can be inuenced by leaders in general and leadership

style in particular (Oorschot et al., 2020). Leaders are considered as the critical PC makers

for followers from this perspective. (Agarwal et al., 2021). Apart from leader and leader-

ship style, employees’ motivation towards job and organization are essential factors for PC

8

A. E. Altunoğlu et al. Demographic dierences matter on job outcomes: psychological contract’s...

and OCB. Shim and Faerman (2017) found that motivation positively related to employees’

engagement in OCB. Vatankhah (2021) suggests that motivation would follow positive per-

formance results and a reduced propensity to participate in negative workplace behavior.

e PC is underlined as a motivation-increasing factor (Vatankhah, 2021). As the literature

suggests, there is an inevitable linkage between OCB, motivation, PC and leadership.

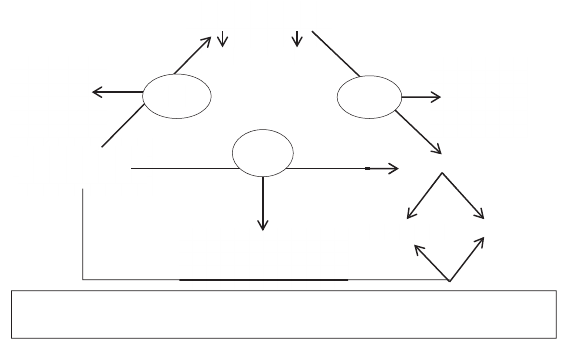

1.6. Model of the study

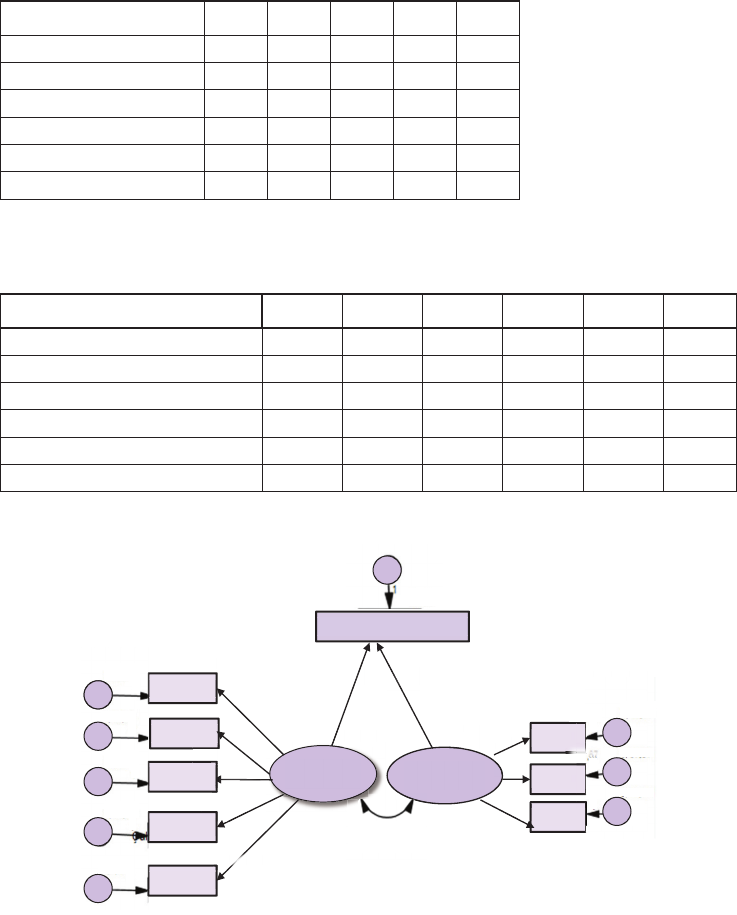

Figure 1 illustrates the research model that we built based on the study’s hypotheses.

H

4a

H

4b

Demographic

Variables

H

H

Psychological

Contract

Constructive

*H4a andH4b: Moderatingroleofthe psychological contract betweendemographic

variablesand jobattitudes

H

2

H

1

Destructive

H

1a,

H

1b,

H

1c,

H

1d,

H

1e

JobAttitudes

H

3

H

2a,

H

2b,

H

2c,

H

2d

H

2e

H

3a,

H

3b,

H

3c,

H

3d

H

3e

Figure 1. e model of the study

2. Methodology

2.1. Overview and participants

Employees in the manufacturing sector from twelve dierent companies located in İzmir,

Turkey, provided the data. e study was conducted between September–November 2019.

All respondents voluntarily participated in the research. e condentiality of respondents

has been stressed and ensured. Four hundred (400) survey questionnaires were distributed

among the companies. Unfortunately, 96 responses were both incomplete and 30 excluded

responses were not available to use. erefore, 274 collected questionnaire results were used

in the study.

2.2. Measurement of variables

In the questionnaire, the data were obtained by providing employees’ beliefs regarding the

factors.

Demographic Variables: Gender and the age of the employee taken into consideration.

Education level was divided into four categories: lower (education up to age 15), average

(certication of high school), high (level of bachelor and master) and upper (level of master

Business, Management and Economics Engineering, 2022, 20(1): 1–22

9

or higher). Tenure is measured by time spent together in the company. Blue-collar and white-

collar workers were considered occupational categories in manufacturing organizations.

Table 1 illustrates the details of the demographic variables.

Table 1. Distribution by demographic variables

Gender Education Having child Position

Parameter Male Female 1 2 3 4 Yes No

Blue-

collar

White-

collar

Number 188 86 85 105 74 9 144 126 175 86

Percentage 68.6% 31.4% 31.1% 38.5% 27.1% 3.3% 53.3% 46.7% 67% 33%

PC Fulllment: is set of 9 items (α = .94) was adopted from Robinson and Rous-

seau (1994) and included the following promises: performance evaluation and feedback,

change management, promotion, remuneration, employee qualication, job security, train-

ing and development, nature of the work, creating the opportunity for the organization

to show him/herself by taking responsibility. In this study, these employer obligations are

considered general promises or expectations relevant to all employees. Participants reacted

to these statements using a ve-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree”; 5 = “strongly

agree”).

Job Satisfaction: e scale was developed by Hackman and Oldham (1975) to determine

individuals’ satisfaction due to the harmony between the individual and the job. e scale

consists of 14 items (α = .94). Participants reacted to these statements using a ve-point

Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree”; 5 = “strongly agree”).

Intention to leave: e scale was developed by Mobley et al. (1978) to measure the level

of the intention of employees to leave their current jobs and consists of 3 items (α = .92).

Reacts to these three statements were made on a ve-point scale (1 = “strongly disagree”;

5 = “strongly agree”).

Organizational Citizenship Behavior: e scale consisting of 19 items (α = .91) was de-

veloped by Basım and Şeşen (2006). Responses to these statements were on ve-point scales

(1 = “strongly disagree”; 5 = “strongly agree”).

Cynicism: e scale developed by Brandes et al. (1999) is based on three dimensions

(α = .92), namely: cognitive, emotional and behavioral and consists of 13 items. Participants

reacted to these 13 expressions using a ve-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree”; 5 =

“strongly agree”).

Task Performance: e scale prepared by Goodman and Syvantek (1999) consists of

9 items (α = .96). Reacts to these statements were made on a ve-point scale (1 = “strongly

disagree”; 5 = “strongly agree”).

In order to minimize the bias in the information-seeking process, the scales in which va-

lidity and reliability analyses were applied and used by numerous researchers in the literature

were selected. Moreover, the questionnaires are delivered to participants working in dierent

companies. Finally, the studies that reached contrary ndings in the literature are reviewed

to avoid bias in developing hypotheses.

10

A. E. Altunoğlu et al. Demographic dierences matter on job outcomes: psychological contract’s...

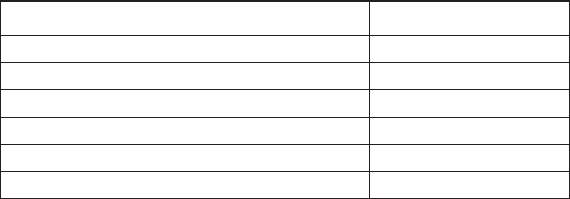

Table 2. e alpha reliabilities among all the scales used in the study

Scale Cronbach Alpha

Job Satisfaction 0.939

Intention to leave 0.921

Organizational Citizenship Behavior 0.911

Cynicism 0.923

Task Performance 0.963

PC 0.940

2.3. Analysis of the data

To test from H1 to H4, we performed Spearman’s rho correlation using SPSS 22.0. Hypothe-

ses 4a and 4b are the hypotheses searching for a mediating role of PCF between demographic

variables and job outcomes. e SEM approach was used because of its ability to deal with

many endogenous, exogenous and latent variables determined as linear combinations of the

observed variables throughout the covariance-based AMOS graphics to investigate the me-

diating role of PCF. e SEM approach can deal with many endogenous and exogenous vari-

ables and latent variables determined as linear combinations of the detected variables (Golob,

2003). e maximum likelihood approach in AMOS was applied to estimate the model.

We examined the goodness-of–t of the model which is proposed based on hypotheses 4a

and 4b. Because of its restrictive structure (Bollen, 1989; Njite & Parsa, 2005; Hooper et al.,

2008) overall t and the local t of individual parameters were conducted using additional

t indices in this study.

In regard of its tenderness to the count of estimated parameters in the model (Hooper

etal., 2008), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) regarded one of the most

revealing t indices (Diamantopoulos & Siguaw, 2000, p. 85; Hooper et al., 2008) indicates

wellness of the model, with obscure but optimally chosen parameter estimates would t the

populations covariance matrix (Byrne, 1998; Hooper et al., 2008). Hooper et al. (2008) stated

that an RMSEA in the range of 0.05 to 0.10 was considered an indicant of satisfactory t

and values above 0.10 can be accepted as inadequate t (MacCallum et al., 1996); between

0.08 to 0.10 provides an average t and below 0.08 indicates a well t (MacCallum et al.,

1996). e comparative t index (CFI) (Bentler, 1990), which is one of the most popularly

reported t indices (Fan et al., 1999) because of being one of the measures least aected by

sample size, accepts that all latent variables are uncorrelated (null/independence model) and

compares the sample covariance matrix with this null model (Hooper et al., 2008). CFI scores

between 0.0 and 1.0 with values closer to 1.0 were accepted indicating a good t (Bentler,

1990). Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) was another parameter to evaluate the goodness-of-t of the

structural regression models. TLI values in the area of 0.90 to 0.95 indicates a good t (Hu &

Bentler, 1999). Incremental t index (IFI) (Bollen, 1989) was also one of the goodness-of–t

indexes to estimate the model of the study. Just as TLI, IFI values in the area of 0.90 to 0.95

also indicates a good t (Bentler, 1980; Marsh et al., 2006).

Business, Management and Economics Engineering, 2022, 20(1): 1–22

11

3. Results

As can be seen from Table 3, there is no connection between gender and job attitudes.

According to Spearman’s rho correlation analysis (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01) results; age was

positively related to job satisfaction (r = 0.142; p < 0.05); OCB (r = 0.204; p < 0.01) and task

performance (r = 0.0137; p < 0.05); and negatively associated with intent to leave (r = –0.238;

p < 0.01) and cynicism (r = –0.232; p < 0.01). Education level was positively associated with

OCB (r = 0.139; p < 0.05), task performance (r = 0.240; p < 0.01) and negatively associated

with intent to leave (r = –0.154; p < 0.05). Tenure was positively related to job satisfaction

(r = 0.159; p < 0.05), OCB (r = 0.160; p < 0.05) and negatively associated with intention to

leave (r = – 0.260; p < 0.01) and cynicism (r = –0.219; p < 0.01). As status is concerned, there

is positive relationship with job satisfaction (r = 0.133; p < 0.05), OCB (r = 0.187; p < 0.01),

task performance (r = 0.154; p < 0.05); except that there is negative relationship with intent

to leave (r = –0.238; p < 0.01) and cynicism (r = –0.142; p < 0.05). Table 3 details the cor-

relation coecients between demographic variables and job attitudes.

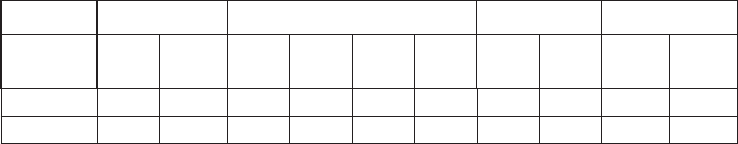

Table 3. Spearman’s rho correlations for the relationship between demographic variables and

job attitudes

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

1. Gender

2. Age .108

3. Education .210

**

.006

4. Tenure .116 .731

**

.029

5. Title .300

**

.138

*

.710

**

.161

*

6. Job satisfaction .019 .142

*

.131 .159

*

.133

*

7. Intent to leave .082 –.238

**

–.154

*

–.260

**

–.238

**

.372

**

8. Organizational

citizenship

–.023 .204

**

.139

*

.160

*

.187

**

.579

**

.224

**

9. Cynicism .066 –.232

**

–.068 –.219

**

–.142

*

.383

**

.620

**

–.173

*

10. Task Performance –.014 .137

*

.240

**

.121 .154

*

.401

**

.174

**

.636

**

–.053

Note: *p < 0.05 **p < 0.01.

According to the results of Spearman’s correlation analyses, PCF was positively associated

with age (r = 0.124; p < 0.05) which supports H2b, education (r = 0.140; p < 0.05) which sup-

ports H2c, tenure (r = 0.148; p < 0.05) which supports H2d, title (r = 0.168; p < 0.05) which

supports H2e. Gender had a minor or insignicant association with the PCF (p > 0.05), not

supporting H2a. Table 4 shows the results of Spearman’s rho correlation analysis.

According to the results, as shown in Table 5, the PC had strong associations with job

outcomes. PCF was positively related to job satisfaction (r = 0.781; p < 0.01) which sup-

ports H3a, OCB (r = 0.565; p < 0.01) which supports H3b and task performance (r = 0.451;

p < 0.01) which supports H3c; negatively related to intent to leave (r = –0.307; p < 0.01) and

cynicism (r = –0.294; p < 0.01) which supports H3d and H3e. ese results support H3.

12

A. E. Altunoğlu et al. Demographic dierences matter on job outcomes: psychological contract’s...

Table 5. Correlations between PCF and job attitudes

1 2 3 4 5 6

1. PC 1.000 .781** –.307** .565** –.294** .451**

2. Job satisfaction .781** 1.000 –.372** .579** –.383** .401**

3. Intent to leave –.307** –.372** 1.000 –.224** .620** –.174**

4. Organizational citizenship .565** .579** –.224** 1.000 –.173* .636**

5. Cynicism –.294** –.383** .620** –.173* 1.000 –.053

6. Task Performance .451** .401** –.174** .636** –.053 1.000

Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

–.26

satisfact

citizens

perfor

Psychological_contract

Demo grap

Positive_joba

.96

Gender

Age

Educatio

Tenure

Title

.22 .65

0; .23

0; 139.91

.95

.47

1

100

1.69

33.62

2.02

1.20

2.63

2.6

3

10.50

1.32

35.13

46.90

e8

e5

e6

e7

e9

e5

e3

e2

e1

1

31.09

0; .20

0; .38

1

1

1

1

1

0; 66.80

e4

0; 65.32

0; 38.37

0; 97.81

0; –.02

1

1

1

71.67

0; 44.44

RMSEA: 0.211, CMIN/DF: 13.248, CFI: 0.666, IFI: 0.674, TLI: 0.400

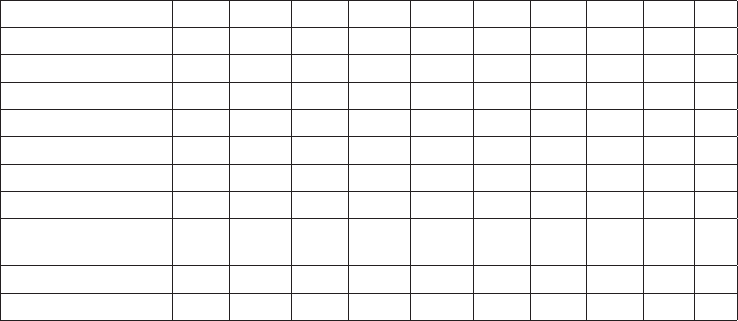

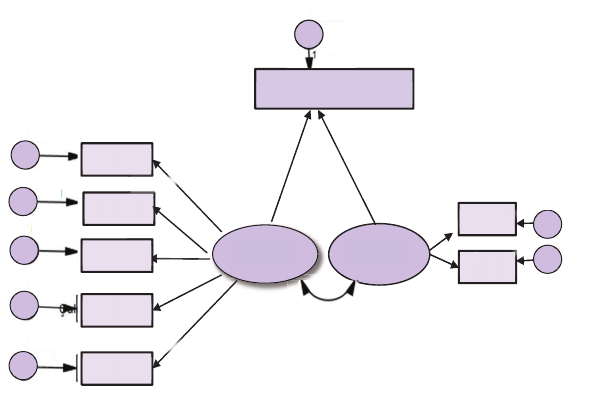

Figure 2. PC mediating role in the eect of demographic variables on constructive job outcomes

According to the model, as shown in Figure 2, demographic variables had an insigni-

cant association with job satisfaction, OCB and task performance which were labeled as

constructive job outcomes in the study (p > 0.05). While there is a signicant relationship

Table 4. Spearman’s rho correlations for the relationship between demographic variables and PCF

1 2 3 4 5

1. Gender

2. Age .108

3. Education –.210

**

.006

4. Tenure .116 .731

**

.029

5. Title –.300

**

.138

*

.710

**

.062

6. PC

–.020 .124

*

.140

*

.148

*

.168

**

Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Business, Management and Economics Engineering, 2022, 20(1): 1–22

13

between demographic variables and constructive job attitudes according to Spearman’s rho

correlation analysis as shown in Table 3, the fact that the relationship is unrelated according

to SEM modeling supports the mediation eect of PCF.

–.27

leave_in

cynism

Psychological_contract

Demograp

Negative_joba

–.37

Gender

Age

Educatio

Tenure

Title

1.84 .65

0; .28

c

c

2.02

1

1.69

33.62

2.02

1.23

2.68

2

.

6

8

10.51

1.32

1

1.00

0; 12.12

0; .37

1

–

1

e8

e6

e7

e8

0; 79.39

0; .68

0; 87.03

31.16

e5

e3

e2

e1

e4

0; .20

1

1

0; 66.80

1

0; 65.31

1

0; –.01

Figure 3. PCF mediating role in the eect of demographic variables on destructive job outcomes

Similar to the constructive job outcomes, demographic variables had insignicant rela-

tionships with job satisfaction, intention to leave and organizational cynicism, which were

considered as destructive job outcomes in the study (p > 0.05). While Spearman’s rho correla-

tion analysis shows a strong relationship between demographic variables and positive work

attitudes (as seen in Table 3), the fact that the relationship is unrelated according to SEM

modeling reinforces the mediation impact of PCF.

4. Dscusson

Although the importance of demographic variables in organizational psychology has long

been recognized, these variables have not been systematically integrated into the PC as a

mechanism for understanding exchange relationships and their impact on job attitudes.

is research intends to analyze the impacts of the demographic variables on job attitudes

and PCF and its possible mediating linkage between demographic variables-job attitudes

are examined in the manufacturing sector. e present research leads in a way to previous

knowledge of PCF. e research was one of the rst studies to formulate hypotheses about the

mediating role of PCF in the relationship between demographic factors and work attitudes.

Employees show dierent levels of perseverance and motivation. Understanding the rea-

sons behind such attitudes may help leaders to motivate and lead them. erefore, personnel

demographic dierences are taken into account to understand their impact on job attitudes

in this study. e results display that there are some interactions between demographic vari-

ables and job attitudes. e very demographic variable considered in the study was gender.

14

A. E. Altunoğlu et al. Demographic dierences matter on job outcomes: psychological contract’s...

Even though the literature provides many papers (A. Sousa-Poza & A. A. Sousa-Poza, 2003;

Bal et al., 2008; Netemeyer et al., 1996; Callister, 2006; Du Plooy & Roodt, 2013), this study

did not underline any interaction between gender and job attitudes. e reason behind such

a nding could be the socio-economic fact of comparatively fewer job prospects for both

men and women in Turkey, and gender has little eect on work attitudes. As far as age is

concerned, it seems to integrate job attitudes. e literature review provides that age is related

to job satisfaction (Kollmann et al., 2020), OCB (Ng et al., 2016), intent to leave (Al Zamel

et al., 2020), cynicism (Chiaburu et al., 2013), task performance (Gajewski et al., 2020). As

expected, the paper displays that older employee showed stronger reactions in positive and

weaker for negative job attitudes.

Older workers seem to respond weakly to adverse events occurring within the organiza-

tion. e reason might be their more signicant emphasis on constructive work interactions

and comfortable relationships with their employer and their more robust control of emotions

compared to the younger employees. e paper ndings note that more educated workers

are unwilling to leave the organization and their OCB and task performance are higher

than less educated ones. e ndings are consistent with the previous studies (Knights &

Kennedy, 2005; Lu et al., 2002; Williams & Shiaw, 1999; Arabacı, 2010; Anseel et al., 2009).

More educated employees might signicantly be more satised with their pay and beholding

a higher position in the organization, which will eventually withdraw them from leaving the

organization. Besides, more educated workers seem to be respectful to colleagues and focus

on collaboration instead of creating problems. More educated workers also manage the duties

given by the organization and fulll their responsibilities.

e reason for such a nding might be the fact that education fosters decision-making

skills and critical thinking. e more a person learns, the more he/she earns. When an in-

dividual learns, he/she begins to innovate, cooperate, and consider all the opportunities that

lie before him/her. e time spent in the company also seems to be related to job attitudes

apart from task performance. e ndings align with previous research (Castellacci & Viñas-

Bardolet, 2020; Lall et al., 2020; Ng & Feldman, 2011; Chiaburu et al., 2013, Sturman, 2003).

At the beginning of their career in an organization, individuals might tend to leave to nd

a “better” job. Besides, employees who stay longer in an organization might resolve job and

career issues which eventually aect their job satisfaction level. ey are highly involved with

the organization resulting in higher OCB. A tenured employee might be better to modify

their expectations to the organizational goals. As job tenure increases, employees may gain

esteem by the spent time in the job that might prevent them from behaving cynically towards

the organization. e results note that being in a dierent hierarchical level (blue-collar and

white-collar worker) might be related to job attitudes apart from job satisfaction. e results

are in line with previous research (Van Hootegem et al., 2021; Baruch et al., 2016; Ersoy et al.,

2011; Koopmans, 2014). Low pay scales and long hours at blue-collar positions may leave

the company and have cynical behaviors. As responsibilities are higher at white-collar posi-

tions, they may collaborate more with co-workers and avoid conicts. Besides, promotional

advances playing a crucial role in overcoming tasks and duties are higher in upper levels.

Because psychological breach of contract is a subjective term, the negative eects on the

outcome can be intensied or absorbed by individual characteristics. For example, women’s

Business, Management and Economics Engineering, 2022, 20(1): 1–22

15

career aspirations are generally much lower than men’s (Blomme et al., 2010). e reason

behind such a statement might be a constructive approach to align family and job obliga-

tions for women. However, our study did not notice any relationship between gender and

PCF. Because of the lack of career opportunities for both men and women in Turkey, workers

are more likely to accommodate organizational policies. e younger the respondents, the

more emphasis on positive work interactions and their comfortable relationship with their

employer and organization was also expected.

Nevertheless, the study did not show any interaction between age and PCF. As Jans-

sens et al. (2003) noted, the study results unveil that less-educated employees seem to react

less emotionally to their incidences of fulllment. Higher educated workers appear to have

higher perceptions of their organization’s incentives. A possible reason for this could be

that even though the organization does not meet the promises, less educated employees are

more likely to accommodate that since nding another job is more dicult for less-educated

workers. e ndings of this study, in line with the literature (Rousseau, 1995; Conway &

CoyleShapiro, 2012), indicate that the positive eects of PCF on the aective engagement of

employees were more excellent and more pronounced for workers with longer tenure in the

organization. One potential explanation for this may be that longer-tenured employees seem

to be more likely to tolerate and view a violation of contract as an inevitable breach that will

be remedied throughout time. e parties can be drawing false conclusions at the beginning

of a relationship while trying to understand the relationship. e parties analyze those con-

sequences and are more specic over time. According to research ndings, white-collar em-

ployees might assume a certain degree of PCF relating to their employer. As the past literature

(Wang et al., 2019; Janssens et al., 2003) argues, the research ndings note that employees of

various levels are likely to demand PCF based on their status as white-collar employees or

more general purposes. Voluntary turnover among blue-collar employees is likely to be less

at the rst sign of instability as the chances of low alternative job opportunities.

PCF had strong associations with job outcomes as the literature suggests. PCF was posi-

tively linked to job satisfaction (Larwood et al., 1998; Zhao et al., 2007), OCB (Robinson

& Morrison, 1995) and task performance (Conway & CoyleShapiro, 2012; Rosen et al.,

2009) negatively related to intent to leave (Chiang et al., 2012) and cynicism (Andersson,

1996; Johnson & O’leary-Kelly, 2003). Keeping commitments stated by the employer dur-

ing recruiting and not feeling betrayed by their organization seems to increase job security

and realize prospects for the future for employees. Such behaviors might eventually result in

higher job satisfaction. Furthermore, an organization that keeps guarantees on the level of

job protection one may expect and has fewer dierences between expected and actual pay

and benets is likely to face less intention to quit behavior since the employer upholds the

promises. It is essential for a company when employees obey company rules and regulations

and help orient new people. Such behaviors display OCB attitudes. Fulllment increases trust

as an employer develops a common concept in the workplace; like good faith and honesty,

trust increases. By developing trust between parties, employees are more likely to obey rules

and regulations even without control. Cynicism is aected by policies such as organization

is running improvement programs, being more concerned about its priorities and needs

than in its employees’ welfare or employees are sceptical when an application was said to be

16

A. E. Altunoğlu et al. Demographic dierences matter on job outcomes: psychological contract’s...

done in the organization. ese policies may have an impact on the level of cynic behavior.

As far as task performance is concerned, in PCF circumstances where employees feel that

an organization lives up to its promises, they are encouraged to take additional actions and

undertake their tasks.

PCF was anticipated to be a mediating variable that helps to clarify why demographic

variables can be linked to constructive attitudes and behaviors. e research supports the

hypothesis by testing the mediating eect between variables (H4a). e ndings underlined

that PCF fully mediated the relationship between demographic variables and constructive

job attitudes. If individuals consider their organization to be considerate and support their

requirements, provide opportunities for safety and development in the workplace, they will

create an obligation to reciprocate the organization with enhanced emotional bonds. Em-

ployees’ views of the exchange contract between themselves and their organizations seem to

mediate the relationship between demographic factors and the constructive job outcomes of

workers. Employees might be motivated by their education level, status or tenure to exert

constructive eorts because of PCF. As far as destructive job attitudes are concerned, the

study ndings also supported the hypothesis (H4b). e negative job outcomes are associ-

ated with PCF. Individual dierences that form the social exchange expectations of employ-

ees can be linked to higher PCF perceptions of employees, and then employees are likely to

exercise destructive job outcomes.

Organizational implications

is present study highlights that, leaders creating a PC in a favourable condition among

employees result in positive and substantial advantages for the organization. In today’s vola-

tile business climate, many organizations nd it challenging to carry out their organizational

commitments consistently and promises to their employees. As a result, organizations face a

problem in eectively monitoring and managing the PC (Turnley et al., 2003). e current

study’s conclusions suggest that organizations review and revise their ideas on the exchange

connection with their workforce as job outcomes of employees are connected to PCF. In

practice, managers and leaders may highlight that such fulllment constitutes an investment

of resources into and a long-term commitment to the employee in addition to satisfying

relational responsibilities. erefore, leaders should place a strong emphasis on increasing

employee commitment levels. In addition, developing a culture of trust and respect fosters

benecial behavioral and attitudinal results among employees (Laulie & Tekleab, 2016). Aside

from this, leaders should encourage open communication with workers to match individual

and corporate interests.

Limitations of the Study and Future Research

is paper applies data from the manufacturing industry operating in Turkey, which may

prevent the generalizability of the paper. Future research is needed to replicate these ndings

on dierent samples in order to generalize ndings. Furthermore, the data is obtained from

a single source which raises the likelihood of common method bias and is focused solely on

self-reports. Finally, individual perceptions may dier across countries and inuence how

employees approach work and their PC with their employer. For instance, because of the

Business, Management and Economics Engineering, 2022, 20(1): 1–22

17

high power distance society in Turkey, followers are likely to provide a biased opinion about

their supervisor, contaminating the overall ndings.

Ultimately, it can be argued that fulllment and breach are two separate PC components

(Conway & Briner, 2005). e paper analyzed the correlations of fulllment to demonstrate

PC. However, the consequences of breaking promises and not fullling obligations may be

dierent. erefore the future studies may focus on the dierent consequences of fulllment

and breach of the PC.

Conclusions

e research was one of the rst studies to formulate hypotheses about the mediating role of

PCF in the relationship between demographic factors and work attitudes. e results display

some interactions between demographic variables and job attitudes. Nevertheless, the study

did not show any interaction between age and PCF. PCF had strong associations with job

outcomes, as the literature suggests. PCF was anticipated to be a mediating variable that helps

to clarify why demographic variables can be linked to constructive attitudes and behaviors.

e current study’s conclusions suggest that organizations review and revise their ideas on

the exchange connection with their workforce as job outcomes of employees are connected

to PCF. In practice, managers and leaders may highlight that such fulllment constitutes an

investment of resources into and a long-term commitment to the employee in addition to

satisfying relational responsibilities. erefore, leaders should place a strong emphasis on

increasing employee commitment levels.

Disclosure statement

Authors declare that they do not have any competing nancial, professional, or personal

interests from other parties.

References

Abela, F., & Debono, M. (2019). e relationship between PC breach and job-related attitudes within a

manufacturing plant. SAGE Open. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018822179

Acker, G. M. (2004). e eect of organizational conditions (role conict, role ambiguity, opportunities

for professional development, and social support) on job satisfaction and intention to leave among

social workers in mental health care. Community Mental Health Journal, 40(1), 65–74.

https://doi.org/10.1023/B:COMH.0000015218.12111.26

Agarwal, U. A., Dixit, V., Nikolova, N., Jain, K., & Sankaran, S. (2021). A PC perspective of vertical and

distributed leadership in project-based organizations. International Journal of Project Management,

39, 249–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2020.12.004

Al Zamel, L. G., Lim Abdullah, K., Chan, C. M., & Piaw, C. Y. (2020) Factors inuencing nurses’

intention to leave and intention to stay: An integrative review. Home Health Care Management &

Practice, 32(4), 218–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/1084822320931363

Andersson, L. M. (1996). Employee cynicism: An examination using a contract violation framework.

Human Relations, 49, 1395–1418. https://do.org/10.1177/001872679604901102

18

A. E. Altunoğlu et al. Demographic dierences matter on job outcomes: psychological contract’s...

Anseel, F., Lievens, F., & Schollaert, E. (2009). Reection as a strategy to enhance task performance aer

feedback. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 110(1), 23–35.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2009.05.003

Arabacı, I. B. (2010). e eects of depersonalization and organizational cynicism levels on the job

satisfaction of educational inspectors. African Journal of Business Management, 4(13), 2802–2811.

Bal, P. M., De Lange, A. M., Jansen, P. G. W., & Van Der Velde, M. (2008). PC breach and job attitudes:

a meta-analysis of age as a moderator. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 72(1), 143–158.

https://do.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2007.10.005

Baruch, Y., Wordsworth, R., Mills, C., & Wright, S. (2016). Career and work attitudes of blue-collar

workers, and the impact of a natural disaster chance event on the relationships between intention

to quit and actual quit behavior. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 25(3),

459–473. https://do.org/10.1080/1359432X.2015.1113168

Basım, H. N., & Şeşen, H. (2006). Örgütsel Vatandaşlık Davranışı Ölçeği Uyarlarma ve Karşılaştırma

Çalışması. Ankara Üniversitesi SBF Dergisi, 61(4), 83–101.

Bem,S. L.(1981).Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex-typing.Psychological Review, 88,

354–364. https://do.org/10.1037/0033-295X.88.4.354

Bentler, P. M. (1980). Multivariate analysis with latent variables: Causal modeling. Annual Review of

Psychology, 31, 419–456. https://do.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.31.020180.002223

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative t indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–

246. https://do.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

Blau, P. M. (1986). Exchange and power in social life. Transaction Publishers.

Blomme, R. J., van Rheede, A., & Tromp, D. M.(2010).e use of the PC to explain turnover intentions

in the hospitality industry: a research study on the impact of gender on the turnover intentions of

highly educated employees.e International Journal of Human Resource Management,21(1),144–

162. https://do.org/10.1080/09585190903466954

Bollen, K. A. (1989). A new incremental t index for general structural equation models. Sociological

Methods & Research, 17, 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124189017003004

Brandes, P., Dharwadkar, R., & Dean, J. W. (1999). Does organizational cynicism matter? Employee

and supervisor perspectives on work outcomes. In Eastern Academy of Management Proceedings

(pp. 150–153).

Byrne, B. M. (1998). Structural Equation Modeling with LISREL, PRELIMS and SIMPLIS: Basic concepts,

applications and programming. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Callister, R. R. (2006). e impact of gender and department climate on job satisfaction and intentions

to quit for faculty in science and engineering elds. Journal of Technology Transfer, 31, 367–375.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-006-7208-y

Castellacci, F., & Viñas-Bardolet, C. (2020). Permanent contracts and job satisfaction in academia:

Evidence from European countries. Studies in Higher Education, 46(9), 1866–1880.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1711041

Chi, S.-C. S., & Chen, S. C. (2007). Perceived PC fulllment and job attitudes among repatriates: An

empirical study in Taiwan. International Journal of Manpower, 28(6), 474–488.

https://doi.org/10.1108/01437720710820008

Chiaburu, D. S., Peng, A. C., Oh, I. S., Banks, G. C., & Lomeli, L. C. (2013). Antecedents and conse-

quences of employee organizational cynicism: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83,

181–197. https://do.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2013.03.007

Chiang, J. C., Jiang, J. J.-Y., Liao, C., & Klein, G. (2012). Consequences of PC violations for is personnel.

Journal of Computer Information Systems, 52(4), 78–87.

Business, Management and Economics Engineering, 2022, 20(1): 1–22

19

Conway, N., & Coyle-Shapiro, J. A. M. (2012). e reciprocal relationship between PC fullment and

employee performance and the moderating role of perceived organizational support and tenure.

Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 85, 277–299.

https://do.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.2011.02033.x

Conway, N., & Briner, R. B. (2005). Understanding PCs at work. A critical evaluation of theory and

research. Oxford University Press.

Cotton, J. L., & Tuttle, J. M. (1986). Employee turnover: A Meta-Analysis and review with implications

for research. e Academy of Management Review, 11(1), 55–70. https://do.org/10.2307/258331

Coyle-Shapiro, J. A.-M., & Kessler, I. (2002). Exploring reciprocity through the lens of the PC: Employee

and employer perspectives. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 11(1), 69–86.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320143000852

Diamantopoulos, A., & Siguaw, J. A. (2000). Introducing LISREL. Sage Publications.

https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849209359

Du Plooy, J., & Roodt, G. (2013). Biographical and demographical variables as moderators in the pre-

diction of turnover intentions. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 39(1), 12–24.

https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v39i1.1070

Ersoy, N. C., Born, M. Ph., Derosa, E., & van der Molen, H. T. (2011). Antecedents of organizational

citizenship behavior among blue- and white-collar workers in Turkey. International Journal of In-

tercultural Relations, 35, 356–367. https://do.org/10.1016/j.jntrel.2010.05.002

Euwema, M. C., Wendt, H., & van Emmerik, H. (2007). Leadership styles and group organizational

citizenship behavior across cultures. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 28, 1035–1057.

https://doi.org/10.1002/job.496

Fan, X., ompson, B., & Wang, L. (1999). Eects of sample size, estimation methods, and model

specication on structural equation modeling t indexes. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 56–83.

https://do.org/10.1080/10705519909540119

Ferris, G., Liden, R., Munyon, T., Summers, J., Basik, K., & Buckley, M. (2009). Relationships at work:

Toward a multidimensional conceptualization of dyadic work relationships. Journal of Management,

35(6), 1379–1403. https://do.org/10.1177/0149206309344741

Gajewski, P. D., Falkenstein, M., önes, S., & Wascher, E. (2020). Stroop task performance across the

lifespan: High cognitive reserve in older age is associated with enhanced proactive and reactive

interference control. NeuroImage, 207, 116430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116430

Golob, T. F. (2003). Structural equation modeling for travel behavior research. Transportation Research

Part B, 37(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-2615(01)00046-7

Goodman, S. A., & Svyantek, D. J. (1999). Person–organization t and contextual performance: Do

shared values matter? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 55(2), 254–275.

https://do.org/10.1006/jvbe.1998.1682

Guest, D.(1998).Is the PC worth taking seriously?Journal of Organizational Behavior,19,649–664.

https://do.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(1998)19:1+<649::AID-JOB970>3.0.CO;2-T

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1975). Development of the job diagnostic survey. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 60(2), 159–170. https://do.org/10.1037/h0076546

Hammer, L. B., Allen, E., & Grigsby, T. D. (1997). Work-family conict in dual-earner couples: Within

individual and crossover eects of work and family. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 50,185–203.

https://do.org/10.1006/jvbe.1996.1557

Hess, N., & Jepsen, D. M. (2009). Career stage and generational dierences in PCs. Career Development

International, 14(3), 261–283. https://do.org/10.1108/13620430910966433

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. R. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for deter-

mining model t. e Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60. www.ejbrm.com

20

A. E. Altunoğlu et al. Demographic dierences matter on job outcomes: psychological contract’s...

Hoque, K. (1999). Human resource management and performance in UK hotel industry. British Journal

of Industrial Relations, 37(3),419–443. https://do.org/10.1111/1467-8543.00135

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cuto criteria for t indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conven-

tional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal,

6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Hu, X., Kaplan, S., & Dalal, R. S. (2010). An examination of blue- versus white-collar workers’ concep-

tualizations of job satisfaction facets. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 76, 317–325.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.10.014

James, M. S. L. (2005). Antecedents and consequences of cynicism in organizations: An examination of

the potential positive and negative eects on school systems [Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation].

e Florida State University, USA.

Janssens, M., Sels, L., & Brande, I. V. (2003). Multiple types of PCs: A six-cluster solution. Human Rela-

tions, 56(11), 1349–1378. https://do.org/10.1177/00187267035611004

Jawahar, I. M., & Carr, D. (2007). Conscientiousness and contextual performance the compensatory

eects of perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange. Journal of Managerial

Psychology, 22(4), 330–349. https://do.org/10.1108/02683940710745923

Johnson, J. L., & O’leary-Kelly, A. M. (2003). e eects of PC breach and organizational cynicism: Not

all social exchange violations are created equal. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24, 627–647.

https://do.org/10.1002/job.207

Kidder, D. L. (2002). e inuence of gender on the performance of organizational citizenship behav-

iors. Journal of Management, 28(5), 629–648. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630202800504

Khan, M. A., Ismail, F. B., Hussain, A., & Alghazali, B. (2020). e interplay of leadership styles, inno-

vative work behavior, organizational culture, and organizational citizenship behavior. SAGE Open.

https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019898264

Knights, J. A., & Kennedy, B. J. (2005). PC violation: Impacts on job satisfaction and organizational

commitment among Australian senior public servants. Applied H.R.M. Research, 10(2), 57–72.

Kollmann, T.,Stöckmann, C.,Kensbock, J. M.,& Peschl, A.(2020). What satises younger versus

older employees, and why? An aging perspective on equity theory to explain interactive eects

of employee age, monetary rewards, and task contributions on job satisfaction.Human Resource

Management,59,101–115. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21981

Koopmans, L. (2014). Measuring individual work performance. CPI Koninklijke Wöhrmann, Zutphen.

Lall, M. D., Perman, S. M., Garg, N., Kohn, N., Whyte, K., Gips, A., Madsen, T., Baren, J. M., & Linden, J.

(2020). Intention to leave emergency medicine: Mid-career women are at increased risk.e West-

ern Journal of Emergency Medicine,21(5), 1131–1139. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2020.5.47313

Lambert, L. S., Edwards, J. R., & Cable, D. M. (2003). Breach and fulllment of the PC: A comparison

of traditional and expanded views. Personnel Psychology, 56(4), 895–934.

https://do.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2003.tb00244.x

Larwood, L., Wright, T., Desrochers, S., & Dahir, V. (1998). Extending latent role of PC theories to pre-

dict intent to turnover and politics in business organisations. Group & Organization Management,

23, 100–123. https://do.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2008.00816.x

Laulie, L., & Tekleab, A. G. (2016). A multi-level theory of PC fulllment in teams. Group and

Organization Management, 41(5), 658–698. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601116668972

Lee, C. H., Hsu, M. L., & Lien,N. H. (2006).e impacts of benet plans on employee turnover: A rm-

level analysis approach on Taiwanese manufacturing industry.e International Journal of Human

Resource Management,17(11),1951–1975. https://do.org/10.1080/09585190601000154

Lu, K. Y., Lin, P. L., Wu, C. M., Hsieh, Y. L., & Chang, Y. Y. (2002). e relationships among turnover

intentions, professional commitment and job satisfaction of hospital nurses. Journal of Professional

Nursing, 18(4), 214–219. https://doi.org/10.1053/jpnu.2002.127573

Business, Management and Economics Engineering, 2022, 20(1): 1–22

21

MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of

sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1(2), 130–149.

https://do.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130

Mackey, J. D., Roth, P. L., Van Iddekinge, C. H., & McFarland, L. A. (2019). A meta-analysis of gender

proportionality eects on job performance. Group & Organization Management, 44(3), 578–610.

https://do.org/10.1177/1059601117730519

Marsh, H. W., Hau, K.-T., Artelt, C., Baumert, J., & Peschar, J. L. (2006). OECD’s brief self-report

measure of educational psychology’s most useful aective constructs: Cross-cultural, psychometric

comparisons across 25 countries. International Journal of Testing, 6(4), 311–360.

https://do.org/10.1207/s15327574jt0604_1

McDonald, D., & Makin, P. (2000). e PC, organisational commitment and job satisfaction of tempo-

rary sta. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 21(2), 84–91.

https://do.org/10.1108/01437730010318174

Michael, J. H., Evans, D. D., Jansen, K. J., & Haigth, J. M. (2005). Management commitment to safety as

organizational support: Relationships with non-safety outcomes in wood manufacturing employees.

Journal of Safety Research, 36(2), 171–179. https://do.org/10.1016/j.jsr.2005.03.002

Mobley, W. H., Horner, S. O., & Hollingsworth, A. T. (1978). An evaluation of precursors of hospital

employee turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 63(4), 408–414.

https://do.org/10.1037/0021-9010.63.4.408

Netemeyer, R. G., Boles, J. S., & McMurrian, R. (1996). Development and validation of work-family

conict and family-work conict scales. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81,400–410.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.81.4.400

Ng, T. W., & Feldman, D. C. (2011). Aective organizational commitment and citizenship behavior:

Linear and non-linear moderating eects of organizational tenure. Journal of Vocational Behavior,

79, 528–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.03.006

Ng,T. W.,Lam,S. S. K., & Feldman,D. C.(2016).Organizational citizenship behavior and counter-

productive work behaviors: Do males and females dier?Journal of Vocational Behavior, 93,11–32.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.12.005

Njite, D., & Parsa, H. G. (2005). Structural equation modeling of factors that inuence consumer inter-

net purchase intentions of services. Journal of Services Research, 5(1), 43–58.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10454446.2014.921868

Oorschot, J., Moscardo, G., & Blackman, A. (2021). Leadership style and PC. Australian Council for

Educational Research, 30(1), 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1038416220983483

Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational citizenship behavior. Lexington Books.

Robinson, S. L., & Morrison, E. W. (1995). PCs and OCB: e eect of unfullled obligations on civic

virtue behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 16(3), 289–298.

https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030160309

Robinson, S. L. (1996). Trust and breach of the PC. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41, 574–599.

https://do.org/10.2307/2393868

Robinson, S. L., & Rousseau, D. M. (1994). Violation the PC: Not the exception but the norm. Journal

of Organizational Behavior, 15(3), 245–259. https://do.org/10.1002/job.4030150306

Robinson, S. L., Kratz, M. S., & Rousseau, D. M. (1994). Changing obligations and the PC: A longitu-

dinal study. Academy of Management Journal, 37, 137–152. https://doi.org/10.2307/256773

Rosen, C., Chang, C., Johnson, R., & Levy, P. (2009). Perceptions of the organizational context and PC

breach: Assessing competing perspectives. Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes,

108(2), 202–217. https://do.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2008.07.003

Rousseau, D. M. (1995). PCs in organizations: Understanding written and unwritten agreements. Sage

Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452231594

22

A. E. Altunoğlu et al. Demographic dierences matter on job outcomes: psychological contract’s...

Sak, R. (2018). Gender dierences in Turkish early childhood teachers’ job satisfaction, job burnout

and organizational cynicism. Early Childhood Education Journal, 46, 643–653.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-018-0895-9

Shim, D. C., & Faerman, S. (2017). Government employees’ organizational citizenship behavior: e

impacts of public service motivation, organizational identication, and subjective OCB norms.

International Public Management Journal, 20(4), 531–559.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2015.1037943

Sousa-Poza, A., & Sousa-Poza, A. A. (2003). Gender dierences in job satisfaction in Great Britain,

1991–2000: Permanent or transitory? Applied Economics Letters, 10(11), 691–694.

https://do.org/10.1080/1350485032000133264

Sturman, M. C. (2003). Searching for the inverted u-shaped relationship between time and performance:

Meta-Analyses of the experience/performance, tenure/performance, and age/performance relation-

ships. Journal of Management, 29(5), 609–640. https://do.org/10.1016/S0149-2063_03_00028-X

Turnley, W. H., Bolino, M. C., Lester, S. W., & Bloodgood, J. M. (2003). e impact of PC fulllment

on the performance of in-role and organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Management,

29(2), 187–206. https://do.org/10.1177/014920630302900204

Van Hootegem, A., Van Hootegem, A., Selenko, E., & De Witte, H. (2021). Work is political: Distribu-

tive injustice as a mediating mechanism in the relationship between job insecurity and political

cynicism. Political Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12766

Vatankhah, S. (2021). Dose safety motivation mediate the eect of PC of safety on ight attendants’

safety performance outcomes?: A social exchange perspective. Journal of Air Transport Manage-

ment, 90, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101945

Vos, A., Buyens, D., & Schalk, R. (2005). Making sense of a new employment relationship: PC-related

information seeking and the role of work values and locus of control. International Journal of Selec-

tion and Assessment, 13(1), 41–52. https://do.org/10.1111/j.0965-075X.2005.00298.x

Wang, X., Sun, J., Liu, X., Zheng, M., & Fu, J. (2019). PC’s eect on job mobility: Evidence from Chinese

construction worker. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 32(1), 1476–1497.

https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2019.1638280

Wayne, S. J., Shore, L. M., & Liden, R. C. (1997). Perceived organizational support and leader-member

exchange: A social exchange perspective.Academy of Management Journal,40, 82–111.

https://do.org/10.2307/257021

Williams, S., & Shiaw, W. T. (1999). Mood and organizational citizenship behavior: e eects of posi-

tive aect on employee organizational citizenship behavior intentions. e Journal of Psychology,

133(6), 656–668. https://do.org/10.1080/00223989909599771

Zhao, H., Wayne, S., Glibkowksi, B., & Bravo, J. (2007). e impact of PC breach on related work-

outcomes: Meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 60, 647–680.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00087.x