POEMS FOR THE MILLENNIUM

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the support of the

LeslieScalapino Memorial Fund for Poetry, which was established

by generous contributions to the University of California Press

Foundation by Thomas J. White and the Leslie Scalapino

– O

BooksFund.

POEMS

for the MILLENNIUM

The University of California

Book of North African Literature

University of California Press

Berkeley Los Angeles London

Volume Four

Edited with commentaries by

Pierre Joris

and

Habib Tengour

This project is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment

for the Arts.

University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United

States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social

sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and

by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information,

visitwww.ucpress.edu.

University of California Press

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

University of California Press, Ltd.

London, England

© by The Regents of the University of California

For credits, please see page . For figure credits, please see page .

Every eort has been made to identify and contact the rightful copyright holders of material

not specifically commissioned for use in this publication and to secure permission, where

applicable, for reuse of all such material. Credit, if and as available, has been provided

forallreprinted material in the credits section of the book. Errors or omissions in credit

citations or failure to obtain permission if required by copyright law have been either

unavoidable or unintentional. The volume editors and publisher welcome any information

that would allow them to correct future reprints.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Poems for the millennium, volume four : the University of California book of North African

literature / edited with commentaries by Pierre Joris and Habib Tengour.

p. cm. — (Poems for the millennium ; )

Includes bibliographical references and index.

---- (cloth) — ---- (pbk.)

. North African literature. I. Joris, Pierre. II. Tengour, Habib.

.

.'—dc

Manufactured in the United States of America

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of / . –

( ) (Permanence of Paper).

To those poets of the Maghreb and the Arab worlds

who stood up against the prohibitions.

This page intentionally left blank

Thanks and Acknowledgments xxxi

Introduction

A BOOK OF MULTIPLE BEGINNINGS

Prologue

The First Human Beings, Their Sons and Amazon Daughters

Hanno the Navigator (Carthage, c. sixth century

b.c.e

.)

from The Periplos of Hanno

Callimachus (Cyrene, 310 – c. 240

b.c.e

.)

Thirteen Epigrammatic Poems

Mago (Carthage, pre-second century

b.c.e

.)

from De Agricultura

Lucius Apuleius (Madaurus, now M’Daourouch, c. 123 – c. 180

c.e

.)

from The Golden Ass, or Metamorphoses

Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus (Carthage, c. 160 – c. 220

c.e

.)

from De Pallio (The Cloak)

from Scorpiace (The Scorpion)

Thascius Caecilius Cyprianus (Carthage, early third century – 258

c.e

.)

from Epistle to Donatus

Lucius Lactantius (Cirta? c. 240 – Trier? c. 320

c.e

.)

from De Ave Phoenice

CONTENTS

viii Contents

Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis (Saint Augustine)

(Thagaste, 354

– Hippo, 430

c.e

.)

from Confessions

from De Doctrina Christiana

from De fide rerum invisibilium

from Psalmus contra partem Donati

Blossius Aemilius Dracontius (Carthage, c. 455 – c. 505

c.e

.)

The Chariot of Venus

De Mensibus (Months)

The Origin of Roses

Luxorius (Carthage, sixth century

c.e

.)

“They say, that when the fierce bear gives birth”

Premature Chariot

FIRST DIWAN

A Book of In-Betweens: Al-Andalus, Sicily, the Maghreb

Prologue

Anonymous Muwashshaha

Some Kharjas

Ibn Hani al-Andalusi (Seville, c. 934 – Barqa, Libya, 973)

Al-Jilnar

Extinction Is the Truth . . .

Ibn Darradj al-Qastalli (958 – 1030)

from Ode in Praise of Khairan al-‘Amiri, Emir of Almería

from Ode in Praise of al-Mansur al-‘Amiri, Emir of Córdoba

Abu Amir Ibn Shuhayd (Córdoba, 992 – 1035)

from Qasida (I)

Córdoba

from Qasida (II)

“As he got his fill of delirious wine”

Gravestone Qasida

Yusuf Ibn Harun al-Ramadi (d. c. 1022)

Hugging Letters and Beauty Spots

Silver Breast

Gold Nails

Contents ix

The Swallow

O Rose . . .

Yosef Ibn Abitur (mid-tenth century – c. 1012)

The “Who?” of Ibn Abitur of Córdoba

Hafsa bint Hamdun (Wadi al-Hijara, now Guadalajara, tenth century)

Four Poems

Samuel Ha-Levi Ibn Nagrella, called ha-Nagid, “the Prince”

(Merida, 993

– Granada, 1055)

Three Love Poems

War Poem

Ibn Hazm (Córdoba, 994 – Niebla, 1064)

My Heart

from The Neck-Ring of the Dove

from “Author’s Preface”

Of Falling in Love while Asleep

Wallada bint al-Mustakfi (Córdoba, 994 – 1091)

Six Poems

Ibn Rashiq al-Qayrawani (also al-Masili)

(Masila, Algeria, c. 1000

– Mazara, Sicily, c. 1064)

from Lament over the Fall of the City of Kairouan

Ibn Zaydun (Córdoba, 1003 – 1071)

Fragments from the Qasida in the Rhyme of Nun

Written from al-Zahra’

Salomon Ibn Gabirol (Malaga, c. 1020 – Valencia, c. 1058)

The -Year-Old Poet

from The Crown of Kingdom

Al Mu‘tamid Ibn Abbad (Seville, 1040 – Aghmat, 1095)

To Abu Bakr Ibn ‘Ammar Going to Silves

To Rumaykiyya

Ibn Hamdis (Noto, Sicily, 1056 – Majorca, 1133)

He Said, Remembering Sicily and His Home, Syracuse

Ibn Labbana (Benissa, mid-eleventh century – Majorca, 1113)

Al-Mu‘tamid and His Family Go into Exile

Two Muwashshahat

x Contents

Moses Ibn Ezra (Granada, c. 1058 – c. 1135)

Drinking Song

Song

Al-A’ma al-Tutili (b. Tudela, c. late eleventh century – d. 1126)

Water-Fire Muwashshaha

Ibn Khafadja (Alcita, province of Valencia, 1058 – 1138)

The River

Yehuda Halevi, the Cantor of Zion (Toledo, 1075 – Cairo, 1141)

from Yehuda Halevi’s Songs to Zion

The Garden

Ibn Quzman (Córdoba, 1078 – 1160)

[A muwashshaha]

The Crow

Abraham Ibn Ezra (1089 – 1164)

“I have a garment”

Abu Madyan Shu’ayb (Sidi Boumedienne) (Cantillana, 1126 –

Tlemcen, 1198)

You Will Be Served in Your Glass

Hafsa bint al-Hajj Arrakuniyya (Granada, 1135 – Marrakech, 1190)

Eight Poems

Ibn Arabi, al-Sheikh al-Akhbar (Murcia, 1165 – Damascus, 1240)

“I believe in the religion of love”

“O my two friends”

The Wisdom of Reality in the Words of Isaac

Abi Sharif al-Rundi (Seville, 1204 – Ceuta, 1285)

Nuniyya

Ibn Said al-Maghribi (Alcalá la Real, 1213 – Tunis, 1274)

The Battle

Black Horse with White Chest

The Wind

Abu al-Hassan al-Shushtari (Guadix, 1213 – Damietta, 1269)

My Art

But You Are in the Najd

Desire Drives the Camels

Contents xi

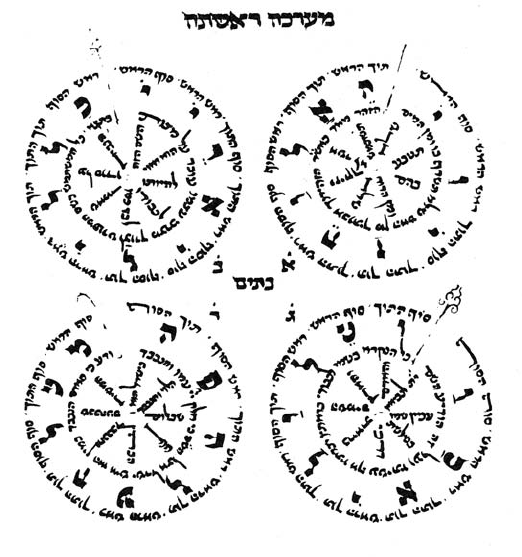

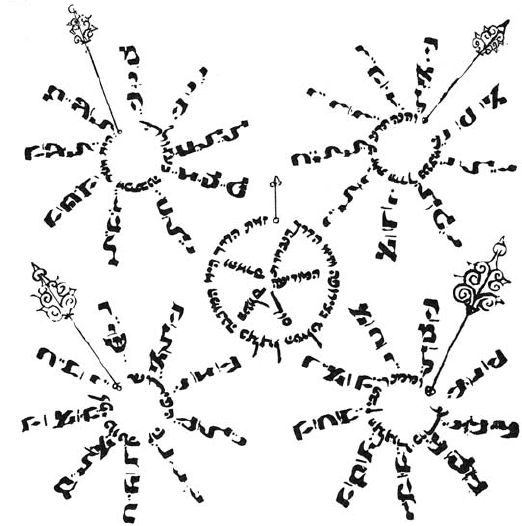

Abraham Abulafia (Saragossa, 1240 – Comino, c. 1291)

How He Went as Messiah in the Name of Angel Raziel

to Confront the Pope

from The Book of the Letter

from Life of the World to Come: Circles

Ibn Zamrak (Granada, 1333 – 1393)

The Alhambra Inscription

THE ORAL TRADITION I

Prologue

Kabyle Origin Tale: “The World Tree and the Image of

the Universe”

from

Sirat Banu Hilal

(I)

Sultan Hassan el Hilali Bou Ali, the Taciturn

Over Whom to Weep

Who Is the Best Hilali Horseman?

Chiha’s Advice

Bouzid on Reconnaissance in the Maghreb

Four Tamachek’ Fables

The Greyhound and the Bone

The Lion, the Panther, the Tazourit, and the Jackal

The Billy Goat and the Wild Boar

The Woman and the Lion

Kabylian Song on the Expedition of 1856

Tuareg Proverbs from the Ahaggar

SECOND DIWAN

Al Adab: The Invention of Prose

Prologue

Ibn Sharaf al-Qayrawani (Kairouan, c. 1000 – Seville, 1067)

On Some Andalusian Poets

On Poetic Criticism

xii Contents

Ibn Rashiq al-Qayrawani (also al-Masili) (Masila, Algeria, c. 1000 –

Mazara, Sicily, 1064)

from Al-‘Umda: “On making poetry and

stimulating inspiration”

Al-Bakri (Huelva, 1014 – Córdoba, 1094)

from Kitab al-Masalik wa-’al-Mamalik (Book of

Routes andRealms)

Abu Hamid al-Gharnati (Granada, 1080 – Damascus, 1169)

from Tuhfat al-Albab (Gift of the Spirit)

Description of the Lighthouse of Alexandria

Chamber Made for Solomon by the Jinns

Ibn Baja (Avempace) (Saragossa, 1085 – Fez, 1138)

from The Governance of the Solitary, Chapter

Al-Idrisi (Ceuta, 1099 – Sicily, c. 1166)

from Al-Kitab al-Rujari (Roger’s Book)

Ibn Tufayl (Cadiz, c. 1105 – Marrakech, 1185)

from Hayy Ibn Yaqzan, a Philosophical Tale

Musa Ibn Maimon, called Maimonides (Córdoba, 1138 – Fostat, 1204)

from The Guide for the Perplexed

Ibn Jubayr (Valencia, 1145 – Egypt, 1217)

from The Travels of Ibn Jubayr: Sicily

Ibn Battuta (Tangier, 1304 – Marrakech, 1369)

from Rihla: Concerning Travels in the Maghreb

Ibn Khaldun (Tunis, 1332 – Cairo, 1406)

from The Muqaddimah, an Introduction to History, Book

Section : “The craft of poetry and the way of

learning it”

Section : “Poetry and prose work with words,

and not withideas”

Sheikh Nefzaoui (Nefzaoua, southern Tunisia – c. 1434)

from The Perfumed Garden

The Names Given to Man’s Sexual Organs

The Names Given to Woman’s Sexual Organs

Contents xiii

Al-Hasan Ibn Muhammad al-Wazzan al-Fasi (Leo Africanus)

(Granada, c. 1488–1554)

from Travel Diaries

Why This Part of the World Was Named Africa

The Manner and Customs of the Arabs Inhabiting Africa

On Fez

A BOOK OF MYSTICS

Prologue

Abu Madyan Shu’ayb (Sidi Boumedienne) (Cantillana, 1126 –

Tlemcen, 1198)

The Qasida in Ra

The Qasida in Mim

Abdeslam Ibn Mashish Alami (Beni Aross region, near Tangier, 1163 – 1228)

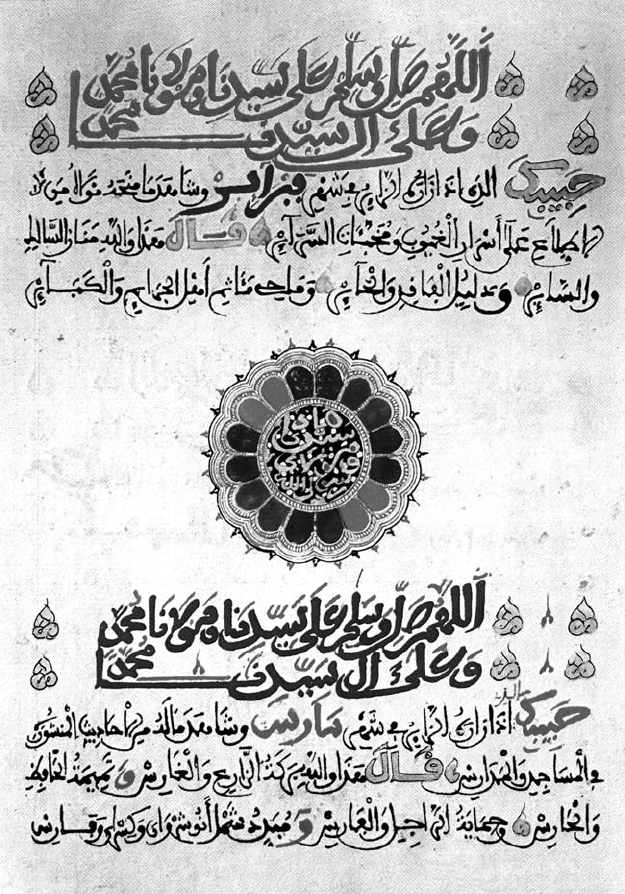

As-Salat Al-Mashishiyah (The Salutation of Ibn Mashish)

Ibn Arabi, al-Sheikh al-Akhbar (Murcia, 1165 – Damascus, 1240)

Our Loved Ones

I Wish I Knew if They Knew

“Gentle now, doves”

“Who is here for a braveheart”

Abu al-Hassan al-Shushtari (Guadix, 1213 – Damietta, 1269)

Layla

Othman Ibn Yahya el Sherki (Sidi Bahlul Sherki) (Tétouan region,

seventeenth century)

from Al-Fiyachiya

Ahmed Ibn ‘Ajiba (Tétouan region, 1747 – 1809)

Qasida

Maxims

Mystical Poetry from Djurdjura

“Tell Me, You Saints from Everywhere”

“Those Who Remember Know It”

“What Dwelling Did I Raise in Ayt-Idjer”

“Bird, Soar Up into the Sky”

xiv Contents

Two Shawia Amulets

Amulet against Poison and Poisonous Animals

Amulet to “Unknot” Headaches and Neuralgias

THIRD DIWAN

The Long Sleep and the Slow Awakening

Prologue

Sidi Abderrahman el Mejdub (Tit Mlil, early sixteenth century – Merdacha,

Jebel Aouf, 1568)

Some Quatrains

Sidi Lakhdar Ben Khlouf (Mostaganem region,

sixteenth

– seventeenth century)

from The Honeycomb

Abdelaziz al-Maghraoui (Tafilalet, 1533 – 1593/1605)

from A Masbah az-Zin (O Beautiful Lamp!)

from Peace Be upon You O Shining Pearl!

Mawlay Zidan Abu Maali (d. Marrakech, 1627)

“I passed . . . ”

Al-Maqqari (Tlemcen, c. 1591 – Cairo, 1632)

On Those Andalusians Who Traveled to the East

Al-Yusi (Middle Atlas, 1631 – 1691)

from Al-Muharat

[Two seasons]

[The city and the country]

Ahmed Ben Triki (Ben Zengli) (Tlemcen, c. 1650 – c. 1750)

from Tal Nahbi (My Pain Endures . . . )

from Sha’lat Niran Fi Kbadi (Burned to the Depths of

My Soul!)

Sid al Hadj Aissa (Tlemcen, 1668 — Laghouat, 1737)

A Borni Falcon Song

A Turkli Falcon Song

Al-Hani Ben Guenoun (Mascara, 1761 – 1864)

from Ya Dhalma (O Unfair Lady!)

Contents xv

Sidi Mohammed Ben Msaieb (d. Tlemcen, 1768)

from O Pigeon Messenger!

Mohammed ben Sliman (d. Fez, 1792)

The Storm

Boumediene Ben Sahla (Tlemcen, late eighteenth – early nineteenth century)

from Wahd al-Ghazal Rit al-Youm (I Saw a Gazelle Today . . .)

Mostefa Ben Brahim (Safa) (Boudjebha, Sidi Bel Abbès province,

1800

– 1867)

Saddle Up, O Warrior!

Mohammed Belkheir (El Bayadh, south of Oran, 1835 – 1905)

Melha!

Moroccan Exile

Exiled at Calvi, Corsica

Si Mohand (Icheraiouen, At Yirraten, c. 1840 – Lhammam-Michelet, 1906)

Three Poems

from Si Mohand’s Journey from Maison-Carrée to Michelet

Mohamed Ibn Seghir Benguitoun (Sidi Khaled, c. 1843 – 1907)

from Hiziya

Sheikh Smati (Ouled Djellal, near Biskra, 1862 – 1917)

Mount Kerdada

Mohamed Ben Sghir (Tlemcen, late nineteenth century)

Lafjar (Dawn)

Ya’l-Warchan (O Dove)

Abdallah Ben Keriou (Laghouat, 1869 – 1921)

“Oh you who worry about the state of my heart”

Hadda (Dra Valley, southern Morocco, late twentieth century)

The Poem of the Candle

A BOOK OF WRITING

Prologue

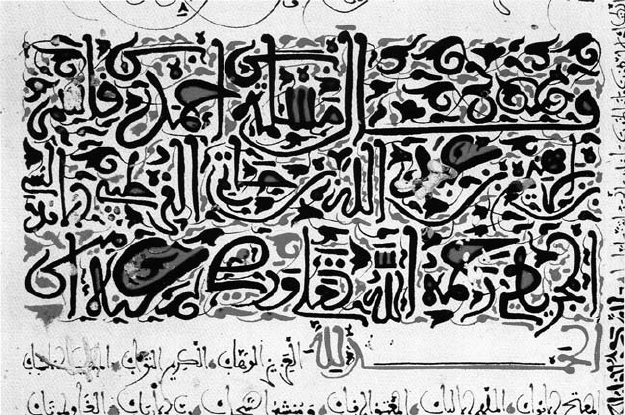

Archaic Kufic Script

Polychrome Maghrebian Script

Maghrebian Script

xvi Contents

Maghrebian Cursive Script

Andalusian Cursive Script

Al-Qandusi

A Bismillah

The Word Paradise

Maghrebian Script: The Two Letters

Lam

-

Alif

Maghrebian Mujawhar Script

FOURTH DIWAN

Resistance and Road to Independence

Prologue

Emir Abd El Kader (Mascara, 1808 – Damascus, 1883)

My Spouse Worries

I Am Love

The Secrets of the Lam-Alif

Mohammed Ben Brahim Assarraj (Marrakech, 1897 – 1955)

Poem I

Poem II

Tahar Haddad (Tunis, 1899 – 1935)

from Muslim Women in Law and Society

Jean El Mouhoub Amrouche (Ighil Ali, 1906 – Paris, 1962)

Adoration of the Palm Trees

Abu al-Qasim al-Shabi (Tozeur, 1909 – Tunis, 1934)

Life’s Will

Mouloud Feraoun (Tizi Hibel, 1913 – Algiers, 1962)

from Journal, 1955 – 1962

Emmanuel Roblès (Oran, 1914 – Boulogne-Billancourt, 1995)

from Mirror Suite

Edmond Amram El-Maleh (Safi, 1917 – Rabat, 2010)

from Taksiat

Mouloud Mammeri (Taourirt Mimoune, Kabylia, 1917 – Aïn Defla, 1989)

from L’Ahellil du Gourara: Timimoun

Contents xvii

Mostefa Lacheraf (Sidi Aïssa, 1917 – Algiers, 2007)

from Country of Long Pain

Mohammed Dib (Tlemcen, 1920 – La Celle-Saint-Cloud, 2003)

from Ombre Gardienne

Guardian Shadow

Guardian Shadow

Guardian Shadow

Dawn Breaks

The Crazed Hour

Nursery Rhyme

A Voice

Bachir Hadj Ali (Algiers, 1920 – 1991)

Dreams in Disarray

Oath

Jean Pélégri (Rovigo, 1920 – Paris, 2003)

Open the Pebble

Nourredine Aba (Aïn Oulmene, 1921 – Paris, 1996)

from Lost Song of a Rediscovered Country

Mohammed Al-Habib El-Forkani (Tahannaout, 1922 – Rabat, 2008)

“In a miserable world”

“My yesterday pursues me”

Frantz Fanon (Fort-de-France, 1925 – Bethesda, Maryland, 1961)

from On National Culture

Jean Sénac (Béni Saf, 1926 – Algiers, 1973)

Dawn Song of My People

News in Brief

The July Massacres

Malek Haddad (Constantine, 1927 – Algiers, 1978)

The Long March

Kateb Yacine (Guelma, 1929 – Grenoble, 1989)

Nedjma, or The Poem or the Knife

from Nedjma

Ismaël Aït Djaafar (Algiers, 1929 – 1995)

from Wail of the Arab Beggars of the Casbah

xviii Contents

Anna Gréki (Batna, 1931 – Algiers, 1966)

The Future Is for Tomorrow

Even in Winter

Henri Kréa (Algiers, 1933 – Paris, 2000)

from Le Séisme au bord de la rivière

Clandestine Travelers

THE ORAL TRADITION II

More Kabylian Origin Stories

The Origin of Shooting Stars

The First Eclipse

The Origin of Menstruation

The Magic Grain: A Tale

Kabyle Proverbs

Songs

Children’s Rain Song

“O night lights of Jew Town”

from

The Adventures of the Jew

. The Bride Who Was Too Large

. The Tail of the Comet

More Riddles and Proverbs

Satirical Nomad Poem

Saharan Gharbi / Western-Style Anonymous Nomad Songs

from

Sirhat Banu Hilal

(II)

Sada Betrays Her Father for Love of Meri

FIFTH DIWAN

“Make It New”: The Invention of Independence I

Prologue

LIBYA

Muhammad al-Faituri (b. al-Janira, Sudan, 1930)

The Story

Contents xix

Incident

The Question and the Answer

Ibrahim al-Koni (b. Fezzan region, 1948)

from Anubis

Dusk

Ashur Etwebi (b. Tripoli, 1952)

from Of Solitude and a Few Other Matters

Faraj Bou al-Isha (b. 1956)

Where Does This Pain Come From?

Here I Am

Wait

Sleep

Fatima Mahmoud (b. Tripoli, mid-twentieth century)

What Was Not Conceivable

Laila Neihoum (b. Benghazi, 1961)

Melting Sun

Khaled Mattawa (b. Benghazi, 1964)

from East of Carthage: An Idyll

TUNISIA

Claude Benady (Tunis, 1922 – Boulogne, Hauts-de-Seine, 2000)

Thirst for a Country . . .

Struggle

Al-Munsif al-Wahaybi (b. Kairouan, 1929)

The Desert

In the Arab House

Ceremony

Midani Ben Salah (Nefta, 1929 – 2006)

In the Train with Them

Noureddine Sammoud (b. Kelibia, 1932)

The Eyes of My Love

Salah Garmadi (Tunis, 1933 – 1982)

Our Ancestors the Beduins

Counsel for My Family after My Death

xx Contents

Shams Nadir (Mohamed Aziza) (b. Tunis, 1940)

from The Athanor

Echoes from Isla-Negra

Abderrazak Sahli (Hammamet, 1941 – 2009)

Clerare Drac

Moncef Ghachem (b. Mahdia, 1946)

Mewall

Fadhila Chabbi (b. Tozeur, 1946)

The Blind Goddess

Engraving Twenty-Nine

Abdelwahab Meddeb (b. Tunis, 1946)

from Talismano

from Fantasia

Muhammad al-Ghuzzi (b. Kairouan, 1949)

Female

Quatrains for Joy

Moncef Ouahibi (b. Kairouan, 1949)

from Under Sargon Boulus’s Umbrella

Khaled Najjar (b. Tunis, 1949)

Stone Castle

Boxes

Poem

Poem

Poem

Poem

Poem

Tahar Bekri (b. Gabès, 1951)

from War to War

from I Call You Tunisia

Amina Said (b. Tunis, 1953)

“Child of the sun and the earth”

“I am a child and free”

Moncef Mezghanni (b. Sfax, 1954)

A Duck’s Speech

The Land of Narrow Dreams

Contents xxi

Adam Fet’hi (b. 1957)

The Blind Glassblower

Cavafy’s Whip

Dorra Chammam (b. Tunis, 1965)

from Reefs and Other Consequences

Amel Moussa (b. Tripoli, 1971)

A Formal Poem

Love Me

Samia Ouederni (b. 1980)

For Tunisia

MAURITANIA

Oumar Moussa Ba (Senegalese village bordering Mauritania, 1921 – 1998)

Well-Known Oxen

The Banu Eyo-Eyo

Plea

Peul Poem

Song of the Washerwoman

Tene Youssouf Gueye (Kaédi, 1928 – 1988)

The Meaning of the Circus

Assane Youssouf Diallo (b. 1938)

from Leyd’am

Djibril Zakaria Sall (b. Rosso, 1939)

To Nelson Mandela

Ousmane-Moussa Diagana (Kaédi, 1951 – Nouakchott, 2001)

from Cherguiya

Mbarka Mint al-Barra’ (b. al-Madhardhara, 1957)

Poetry and I

Aïcha Mint Chighaly (b. Kaédi, 1962)

Praise on the Site of Aftout

Nostalgic Song about Life

WESTERN SAHARA

Bahia Mahmud Awah (b. Auserd, 1960)

The Books

I Have Faith in Time

xxii Contents

A Poem Is You

Orphan at a Starbucks

Zahra el Hasnaui Ahmed (b. El Aaiún, 1963)

Voices

“They Say That the Night”

Gazes

Mohammed Ebnu (b. Amgala, 1968)

Exile

Children of Sun and Wind

Message in a Bottle

Chejdan Mahmud Yazid (b. Tindouf, 1972)

Sirocco

The Expectorated Scream

Enough!

Limam Boicha (b. Atar, 1973)

The Roads of the South

Boughs of Thirst

Existence

A BOOK OF EXILES

Prologue

DIASPORA

Mario Scalési (Tunis, 1892 – Palermo, 1922)

Symbolism

New Year’s Gift

Sunrise

Words of a Dying Soldier

Envoy

Jacques Berque (Frenda, 1910 – Saint-Julien-en-Born, 1995)

from “Truth and Poetry”: On the Seksawa Tribe

Jacques Derrida (Algiers, 1930 – Paris, 2004)

from The Monolingualism of the Other, or

The Prosthesis of Origin

Contents xxiii

Hélène Cixous (b. Oran, 1937)

Letter-Beings and Time

Hubert Haddad (b. Tunis, 1947)

A Quarter to Midnight

DIASPORA

Paul Bowles (New York, 1910 – Tangier, 1999)

from Africa Minor

Juan Goytisolo (b. Barcelona, 1931)

Dar Debbagh

Cécile Oumhani (b. Namur, 1952)

Young Woman at the Terrace

THE ORAL TRADITION III

Prologue

Aissa al Jarmuni al Harkati (Sidi R’ghis, now Oum El Bouaghi,

1885

– Aïn Beïda, Oum El Bouaghi province, 1946)

Poem about His Country, the “Watan”

Quatrain about the Jews at a Wedding Party in

the “Harat Lihud” Quarter in Constantine

Quatrain about the Sufi Sheikh Sidi Muhammad ben Said’s

Young Wife Who Had Died the Night Before

Two Quatrains about Human Existence

Two Quatrains on the Shawia People Sung at

the Olympia in Paris ()

Poem about Education

Two Lyrics from al Harkati’s Recorded Songs

Oh Horse Breeder!

The Slender One

Qasi Udifella (1898 – 1950)

Four Poems

Mririda N’aït Attik (Megdaz, c. 1900 – c. 1930)

The Bad Lover

What Do You Want?

The Brooch

xxiv Contents

The Song of the Azria

Slimane Azem (Kabylia, 1918 – Moissac, France, 1983)

Taskurth(The Partridge)

Cheikha Rimitti (Tessala, 1923 – Paris, 2006)

He Crushes Me

The Girls of Bel Abbès

The Worst of All Shelters

Kheira (b. Tunisia, c. 1934)

You Who Rebel against Fate, Rise and Face What

God Has Ordained

Mohammed Mrabet (b. Tangier, 1936)

Si Mokhtar

Hawad (b. north of Agadez, 1950)

from Hijacked Horizon

Lounis Aït Menguellet (b. Ighil Bouammas, 1950)

Love, Love, Love

Mohammed El Agidi (Morocco, twentieth century)

“Tell me Sunken Well”

Matoub Lounes (Taourirt Moussa, 1956 – Tizi Ouzzou, 1998)

Kenza

My Soul

FIFTH DIWAN

“Make It New”: The Invention of Independence II

ALGERIA

Mohammed Dib (Tlemcen, 1920 – La Celle-Saint-Cloud, 2003)

from Formulaires

Jean Sénac (Béni Saf, 1926 – Algiers, 1973)

Man Open

Heliopolis

Song of the Mortise

I Like What’s Dicult, Said You

The Last Song

Contents xxv

Kateb Yacine (Guelma, 1929 – Grenoble, 1989)

from Le Polygone Étoilé

Nadia Guendouz (Algiers, 1932 – 1992)

Green Fruit

On Rue de la Lyre

st May

Assia Djebar (b. Cherchell, 1936)

Poem for a Happy Algeria

from Fantasia: An Algerian Cavalcade

Malek Alloula (b. Oran, 1937)

from The Colonial Harem

Mourad Bourboune (b. Jijel, 1938)

from The Muezzin

Nabile Farès (b. Collo, 1940)

Over There, Afar, Lights

Rachid Boudjedra (b. Aïn Beïda, Oum El Bouaghi province, 1941)

from Rain (Diary of an Insomniac)

Abdelhamid Laghouati (b. Berrouaghia, 1943)

“To embrace”

Indictment

Youcef Sebti (Boudious, 1943 – Algiers, 1993)

The Future

Hell and Madness

Ismael Abdoun (b. Béchar, 1945)

“Faun-eye’d iceberg burn”

Rabah Belamri (Bougaa, 1946 – Paris, 1995)

“Have we ever known”

Inversed Jabbok

Habib Tengour (b. Mostaganem, 1947)

from Gravity of the Angel

Hamida Chellali (b. Algiers, 1948)

“In the days”

from The Old Ones

xxvi Contents

Hamid Skif (Oran, 1951 – Hamburg, 2011)

Pedagogical Couscous Song

Poem for My Prick

Here I Am

Hamid Tibouchi (b. Tibane, 1951)

from The Young Traveler and the Old-Fashioned Ghost

Mohamed Sehaba (b. Tafraoui, 1952)

Far from Our Erg

The Bird No Longer Sings

I Miss Something . . .

Abdelmadjid Kaouah (b. Aïn-Taya, near Algiers, 1954)

Neck

Modern Bar

Majestic

Tahar Djaout (Azeffoun, 1954 – Algiers, 1993)

March ,

Amin Khan (b. Algiers, 1956)

Vision of the Return of Khadija to Opium

Mourad Djebel (b. Annaba, 1967)

Summer

Mustapha Benfodil (b. Relizane, 1968)

from I Conned Myself on a Levantine Day

Al-Mahdi Acherchour (b. Sidi-Aïch, 1973)

In the Emptiness

Return to the Missed Turn

Samira Negrouche (b. Algiers, 1980)

Coee without Sugar

MOROCCO

Driss Chraïbi (El Jadida, 1926 – Drôme, France, 2007)

from Seen, Read, Heard

Mohammed Sebbagh (b. Tétouan, 1929)

from Seashell-Tree

from Candles on the Road

Contents xxvii

A Brief Moment

The Missing Reader

Maternal Instinct

In Shackles

If I Had a Friend

Two Poems

Mohamed Serghini (b. Fez, 1930)

Poem I

Poem III

from Assembly of Dreams

Abdelkrim Tabbal (b. Chefchaouen, 1931)

To the Horse

Happiness

The Speech

Absent Time

Zaghloul Morsy (b. Marrakech, 1933)

from From a Reticent Sun

Mohamed Choukri (Aït Chiker, 1935 – 2003)

from The Prophet’s Slippers

Ahmad al-Majjaty (Casablanca, 1936 – 1995)

Arrival

Disappointment

The Stumbling of the Wind

Abdelkebir Khatibi (El Jadida, 1938 – Rabat, 2009)

from Class Struggle in the Taoist Manner

from Love in Two Languages

Mohammed Khaïr-Eddine (Tafraout, 1941 – Rabat, 1995)

Horoscope

Indictment

from I, Bitter

Ali Sadki Azayku (Taroudant, 1942 – 2004)

Neighbor to Life

The Shadows

Mother Tongue

xxviii Contents

Abdellatif Laâbi (b. Fez, 1942)

The Portrait of the Father

The Anonymous Poet

Letter to Florence Aubenas

Mostafa Nissabouri (b. Casablanca, 1943)

from Approach to the Desert Space

Abdelmajid Benjelloun (b. Fez, 1944)

The Flute of Origins, or The Taciturn Dance

Eternity Comes Down on the Side of Love

A Woman to Love as One Would Love to Revive after Death

Tahar Ben Jelloun (b. Fez, 1944)

from Harrouda

Mohamed Sibari (b. Ksar el Kebir, 1945)

from Very Far Away . . .

Confession

Lady Night

Malika El Assimi (b. Marrakech, 1946)

Things Having Names

Smoke

Mariam

The Snout

Mohammed Bennis (b. Fez, 1948)

from The Book of Love

For You

Letter to Ibn Hazm

Seven Birds

Ahmed Lemsyeh (b. Sidi Ismail, 1950)

Fragments of the Soul’s Shadow

I Miss My Self

Rachida Madani (b. Tangier, 1951)

from Walk through the Debris . . .

Mohammed al-Ashaari (b. Moulay Idriss Zerhoun, 1951)

from A Vast Space . . . Where There’s No One

Contents xxix

Medhi Akhrif (b. Assilah, 1952)

from The Tomb of Helen

Half a Line

Abdallah Zrika (b. Casablanca, 1953)

from Drops from Black Candles

from Some Prose: My Sister’s Scream in Black and White

Mubarak Wassat (b. Mzinda, Safi region, 1955)

Balcony

Innocence

The Time of the Assassins

Hassan Najmi (b. Ben Ahmed, 1959)

The Window

Couplets

The Blueness of Evening

The Train Yard

Waafa Lamrani (b. Ksar el Kebir, 1960)

Alphabet Fire

A Shade of Probability

The Eighth Day

Ahmed Barakat (Casablanca, 1960 – 1994)

Afterwards

Black Pain

The Torn Flag

Touria Majdouline (b. Settat, 1960)

A Minute’s Speech

Out of Context

Ahmed Assid (b. Taourmit, Taroudant province, 1961)

Prayer

A Chamber the Color of Disgust

Suns

Mohamed El Amraoui (b. Fez, 1964)

En Quelque

Jerusalem

Mohammed Hmoudane (b. Maaziz, 1968)

from Incandescence

xxx Contents

Ouidad Benmoussa (b. Ksar el Kebir, 1969)

Restaurant Tuyets

This Planet . . . Our Bed

Road of Clouds

Omar Berrada (b. Casablanca, 1978)

Subtle Bonds of the Encounter

Credits

Index of Authors

xxxi

THANKS AND

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

As is the custom, we will thank those individuals who have helped us with

the labor of this book and are closest to us toward the end of this note. But

to start with, we want to acknowledge the push of what we would like to

call the extreme contemporariness of history, as the edge of cultural and

political events — in this case those of the so-called Arab Spring — coincided

with and energized the final year of the redaction of this assemblage. In no

small way are those events a vindication of a project that has been in the

works for more than a decade now — with at least one of its aims being an

assertion of the cultural importance of the Arabo-Berber heritage for the

world. So our admiration and thanks go to all those in Tunisia and Libya,

but also in Egypt and beyond, who have decided to take to the streets and

reawaken the open-minded and pluralistic spirit that once animated the

world of al-Andalus and the Maghreb. Upmost in our minds as we worked

on this project were those Maghrebian poets, writers, and artists who suf-

fered torture, imprisonment, and, all too often, death at the hands of repres-

sive state systems, both colonial and postcolonial. We remember and thank

all of them. May the names of two assassinated Algerian poets who were our

personal friends — Youcef Sebti and Tahar Djaout — stand in for all of those

courageous fighters for freedom and justice too numerous to name.

It is impossible to list in extenso all the Maghrebian, European, and

American poets, writers, and scholars who contributed advice and counsel

during the long decade it took to bring the idea of this book to fruition. But

among those who functioned as continuous advisers, we give special thanks

to the poets Mohammed Bennis, Abdellatif Laâbi, Khaled Mattawa, and

Abdelwahab Meddeb. Marilyn Hacker and Madeleine Campbell have been

wise advisers and excellent translators. Joseph Mulligan has done amazing

gathering and translating from the Spanish for the Western Sahara sec-

tion, and beyond. In Paris, Éditions de la Diérence has graciously given us

xxxii Thanks and Acknowledgments

permission to use the work of many of its Maghrebian authors — shukran!

More than thanks — as without his unstinting help and hard work as both

gatherer and translator (especially of the melhun materials) this would be

a dierent and much diminished book — are due to the Algerian poet and

scholar Abdelfetah Chenni, who by right could be named the third coeditor.

We also want to express our thanks and gratitude to poet, translator and

scholar Peter Cockelbergh, who assisted throughout the process of this book

with advice and translation help, and whose proofreading skills came to our

rescue in that final proverbial nick of time. On this side of the ocean, we

are deeply grateful to the other cofounder of the Poems for the Millennium

series, Jerome Rothenberg, whose continuous support and advice have been

invaluable, and to Charles Bernstein, whose enthusiasm for and defense of

this project have been beyond the call of duty.

Institutional help has also played its role in advancing the cause of the

book, and we thank the Ministère de la Culture of Luxembourg, which

enabled several research trips to Algeria and Morocco. More locally we

are grateful to the National Endowment for the Arts for its support and

to the Leslie Scalapino Memorial Fund for Poetry, which was established

by generous contributions to the University of California Press Foundation

by Thomas J. White and the Leslie Scalapino

– O Books Fund. Our team at

University of California Press, led by Rachel Berchten, has been unstint-

ing in its eorts to ensure a healthy natural birth to this oversize brainchild

of ours. Of course the two editors could not have completed this task if

Nicole Peyrafitte, son Miles Joris-Peyrafitte, and daughter Hind Tengour

didn’t have their backs during the often dicult — though always exhilarat-

ing — nomadic wanderings that the gathering and shaping of this volume

demanded.

1

This book has been incubating in our minds for a quarter century now, and

we have been gathering material for even longer — with the aim of assem-

bling and contextualizing a wide range of writing from North Africa previ-

ously unavailable in the English-speaking world. The result is, we believe,

a rich if obviously not full dossier of primary materials of interest not only

to scholars of world literature, specialists in the fields of Arab and Berber

studies, but also to a general audience and to contemporary readers and

practitioners of poetry who, to deturn a Frank O’Hara line, want “to see

what the poets in North Africa are doing these days.” It is a project meant as

a contribution to the ongoing reassessment of both the literary and cultural

studies fields in our global, postcolonial age. Its documentary and trans-

genre orientation means that it not only features major authors and literary

touchstones but also provides a first look at a wide range of popular cultural

genres, from ancient riddles, pictographs, and magic formulas to contem-

porary popular tales and songs, and is also in part a work of ethnopoet-

ics. Drawing on primary resources that remain little known and dicult

of access, and informed by the latest scholarship, this gathering of texts

illuminates the distinctively internationalist spirit typified by North African

culture through its many permutations.

A combination of traditional and experimental literary texts and ethno-

poetic material, this fourth volume in the ongoing Poems for the Millennium

series of anthologies is a natural progression from its predecessors. Jerome

Rothenberg and Pierre Joris edited the first two volumes, which present

worldwide experimental poetries of the twentieth century. Volume , as

a historical “prequel,” covers the new and experimental poetries of nine-

teenth-century Romanticism worldwide. This volume — which we have at

times half-jokingly thought of as a “sidequel,” for its southerly departure

from Europe and North America, the series’s main focus — is conceptually

INTRODUCTION

2 Introduction

linked to volume in its attempt to present the historical processes that led

to the most innovative contemporary work. And the first two, core volumes

in fact include — although in a minimal manner, of necessity — a few of the

Maghrebian authors who are revolutionizing writing in their countries

today. Those books also show the importance of oral literature in contem-

porary experimentation, a theme deepened and broadened in the volume at

hand.

Throughout the years of work on this book, our shorthand working title

was “Diwan Ifrikiya,” which has the advantage of being brief and concise,

though the disadvantage of being slightly obscure compared to the longer,

less elegant, but more explicit appellation Book of North African Literature.

“Diwan Ifrikiya”

— as we refer to it throughout this introduction — combines

the well-known Arabic word for “a gathering, a collection or anthology” of

poems, diwan, with one of the earliest names of (at least part of) the region

that this book covers. Ifrikiya is an Arabization of the Latin word Africa —

which the Romans took from the Egyptians, who spoke of “the land of the

Ifri,” referring to the original inhabitants of North Africa. The Romans

called these people Berbers, but they call themselves the Amazigh, and even

today tribal names — such as Beni Ifren — in their language, Tamazight,

include words derived fromifri.

“Diwan Ifrikiya” is thus an anthology of the various and varied written

and oral literatures of North Africa, the region known as the Maghreb, tra-

ditionally described as situated between the Siwa Oasis to the east (in fact,

inside the borders of Egypt) and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, spanning

the modern nation-states of Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco — as well

as the desert space of the Sahara. Given the nomadic habits of the Tuareg

tribes, the larger Maghreb can include parts of Mali, Niger, and Chad, plus

Mauritania, to the great desert’s southwest, famous for its manuscript col-

lections. (The spread of the various Amazigh peoples is also describable in

terms of their basic food, namely the breadth and limits of the use of rolled

barley and wheat flour, or couscous.) We have also included the extremely

rich and influential Arab-Berber and Jewish literary culture of al-Andalus,

which flourished in Spain between the ninth and fifteenth centuries. This

culture was intimately linked to North Africa throughout its existence and

even after its final disappearance following the Reconquista, given that a

great part of Spain’s Muslim and Jewish population fled toward the south

then, seeking refuge in North Africa.

The time span of “Diwan Ifrikiya” reaches from the earliest inscrip-

tions — prehistoric rock drawings in the Tassili and Hoggar regions in the

southern Sahara; the first Berber pictograms

— to the work of the current

generation of postindependence and diasporic writers.Such a chronology

takes in diverse cultures, including Amazigh, Phoenician, Jewish, Roman,

Introduction 3

Vandal, Arab, Ottoman, and French constituents. It also covers a range of

literary genres: although concentrating on oral and written poetry and nar-

ratives, especially those which invent new or renew preexisting literary tra-

ditions, our gathering also draws on historical and geographical treatises,

philosophical and esoteric traditions and genres, song lyrics, current prose

experiments in the novel and short story, and so forth.

From a wider or outside perspective, the overall chronological arrange-

ment makes perceptible the crucial importance of this region in the devel-

opment of Western culture, adding hitherto little-known or unknown his-

torical data while showing how the Maghreb’s present-day postcolonial

achievements are major contributions to global world culture. In ancient

times, the Maghreb was seen as the Roman Empire’s breadbasket

— we hope

this book shows that at the intellectual and artistic levels this has remained

so ever since. To be candid: North Africa is a region whose cultural achieve-

ments — including their impact on and importance for Western culture —

have been not only passively neglected but often actively “disappeared” or

written out of the record. This is true for the majority of this area’s autoch-

thonous writers and thinkers, even those few whose achievements have been

recognized north of the Mediterranean — often because they became dias-

pora figures working in Europe. A few examples may suce: Augustine is

certainly considered a major church father, but his North African roots, if

not totally obscured, are given little credit. Apuleius, the author of one of

the first prose narratives that prefigure our novel,is known as a Latin or late

Roman writer, not a Maghrebian. It is also interesting to note in this con-

text that the last poet whose mother tongue was Latin was a Carthaginian,

and that by an odd circumstance the first nonoral poet in our chronology,

Callimachus — whose forebears immigrated to Cyrenaica (Libya), possibly

from the Greek island of Thera, where the first ruler of the Battiad Dynasty

came from — wrote in Greek.

We know that during the heyday of Arab-Islamic culture, and more spe-

cifically between and .., scribes and thinkers first safeguarded,

then translated and transmitted to the Europeans, much of the Greek phi-

losophy and science that we pride ourselves on as the roots of Western

civilization. Many lived and worked in al-Andalus, that thriving center of

culture on European shores — a place where a millennium ago Arabs, Jews,

and Christians learned to live together in productive peace. Yet the core

figures of this period of Arab culture, such as Ibn Khaldun, Ibn Battuta,

and Al-Hasan Ibn Muhammad al-Wazzan al-Fasi — whom we know as Leo

Africanus — if not unknown, are seriously marginalized in the West. Lip

service may be paid to, say, Ibn Khaldun, as the father of sociology, or a

French author of Lebanese origin may write a successful novel based on the

figure of Leo Africanus, but the actual texts of these writers, thinkers, and

4 Introduction

mapmakers are rarely available to the Anglophone world — or are available

only to specialists or, again, without much context with which to read and

appreciate them.

Even if Arab culture went into a long sleep and the high-cultural pro-

ductions of the Maghreb often became mere imitations of the classical

Mashreqi (Near Eastern) models — and thus less creatively innovative — dur-

ing the centuries between the fall of al-Andalus to the Spanish Christians

and the conquest of North Africa by the colonial powers, there was much

cultural activity then. This is especially true for the autochthonous Berber

cultures which, despite having been Arabized (at least to the degree of

accepting Islam, in many instances in a modified, maraboutic form), kept

alive vital modes of popular oral literature, for example Berber tales and sto-

ries, plus elaborations and updated versions of the Arab-Berber epic of the

Banu Hillal confederation. European anthropologists gathered much of this

ethnopoetic material in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, but it

has since faded from view, we surmise both from a lack of interest shown by

the old colonizers and from a justifiable and understandable unease among

Maghrebians toward this material so often labeled “primitive” or “prelit-

erary” by those who recorded it. Besides which, the current Maghrebian

societies are too busy trying to invent their own contemporaneity and to

modernize themselves to have much time or desire to invest their limited

resources in reassessing their remote pasts. If this anthology helps to dispel

some of this unease or even incites other researchers and writers to look

deeper into these hidden and buried histories, it will have accomplished one

of its main goals.

The longtime neglect of such a major cultural area is part of a wider, now

well-documented, Eurocentrism; permit us to cite an example germane to

the project at hand. In the early days of Modernism, Ezra Pound spent time

and energy establishing the roots of European lyric poetry, which he located

in the French/Occitan troubadour tradition, a lineage that has become

canonical over the past century. Open your American Heritage Dictionary,

and you’ll see that it gives the Latin tropare as the root of troubadour

— an

etymology that on closer inspection, however, turns out to be reconstructed,

presumed, and unattested (i.e., marked with an asterisk). In fact, the field of

romance philology has done everything in its power to negate any traces of

a non-European origin of — or even strong foreign influence on — European

lyric poetry. And yet it has been known since at least , via the work of

the Spanish linguist Julián Ribera, that the obvious root of troubadour is the

Arabic tarab, “to sing,” specifically to sing a musical poetry that produces

an exalted state. (One could also link this ecstatic sense of tarab to Federico

García Lorca’s duende.) Pound, like nearly all other European and American

writers and researchers, was looking for European origins

— though in his

Introduction 5

essay on the troubadours he had a vague inkling that something else

was going on, as far as the tunes of the troubadours’ canzos are concerned:

“They are perhaps a little Oriental in feeling, and it is likely that the spirit of

Sufism is not wholly absent from their content.” It is that kind of belittling

and, in the final analysis, deeply denigrating attitude that “Diwan Ifrikiya”

addresses and, we hope, redresses somewhat.

This anthology is organized into five approximately chronological diwans,

inside which the authors appear in chronological order. Reading through

them, one can get a sense of temporal progression and thus of the changes

brought by history. The First Diwan, subtitled “A Book of In-Betweens:

Al-Andalus, Sicily, the Maghreb,” starts with an early, anonymous muwash-

shaha

— that lyrical poetic form invented in al-Andalus which moved Arabic

poetry away from the imitation of classical qasida models going back to

pre-Islamic forms. After a wide presentation of Arab and Jewish poets who

made al-Andalus so incredible and possibly unique, the diwan ends with Ibn

Zamrak’s wonderful description of the Alhambra.

The next diwan, “Al Adab: The Invention of Prose,” presents a range of

materials — from literary criticism through Ibn Khaldun’s writings (the ur-

texts of what will become sociology) to historical, literary, and cultural doc-

uments — that will give the reader a sense of the breadth and width of this

pulsating and formative civilization. The Third Diwan, “The Long Sleep

and the Slow Awakening,” moves us from the end of the fifteenth century

(and thus the end of al-Andalus, which can be dated to the final victory of

the Spanish Reconquista, in ) to the end of the nineteenth, a period

during which Arab culture — both in its cradle, the Middle East, and in its

Western extension, the Maghreb (in fact, in Arabic Maghreb means “West,”

in both a geographical and a deeper cultural, even mystical, sense) — fell

prey to what is usually called decadence, at the political, social, and cultural

levels. For the Maghreb, however, even these centuries held creative excite-

ment: it was then that one of the great poetic forms of North Africa, the mel-

hun, came into its own by revitalizing its classical roots through both formal

and linguistic innovations, including the use of the Maghrebian vernacular.

The innovations and final grandeur of these poems, song lyrics really, are

dicult to bring across in translation; suce it to say that the poems have

stood the test of time and still represent the core repertoire of the great mel-

hun singers.

The Fourth Diwan, “Resistance and Road to Independence,” covers about

one hundred years: from the mid-nineteenth (the aftermath of the French

colonization of Algeria) to the mid-twentieth century, that moment when

the people of the Maghreb begin to demand

— and fight for — sovereignty.

The shock of colonization may at first have numbed these populations, but

in the twentieth century they produced a literature of resistance while on

6 Introduction

what we have called the long road to independence. A specifically national or

nationalist thought also emerged then, as a range of dierences — between,

before all, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco — rose to the surface and began

to be theorized. Emblematic of this period are the diwan’s two framing fig-

ures: Emir Abd El Kader, born in Mascara in , the great nomad war-

rior who gathered the tribes to fight the French, was a superb writer and

poet, a Sufi mystic, and a follower of Ibn Arabi’s thought, who died in exile

in Damascus; and Henri Kréa, the French-Algerian poet who fought for

Algeria’s independence and died in Paris in . An amazing span

— with

other amazing figures, such as Abu al-Qasim al-Shabi, Frantz Fanon, and

Kateb Yacine, whose work includes some of the first great classics of modern

Maghrebian literature.

A double diwan concludes the book: although it covers only the past sixty

or so years, its size demanded the split into two sections. We have divided it

according to geography, grouping the two northeastern Maghreb countries

(Libya and Tunisia) with the two relatively small countries in the south-

west of our area, namely, Mauritania and Western Sahara, while keeping

Algeria and Morocco for part . The writers in this diwan are those who

came of age at the moment of independence and the two to three generations

since then. This diwan’s size and literary achievement show that the great

richness that characterized early Maghrebian culture, even if buried for a

time by the “decadence” of one of its foundational cultures and then by the

strictures of European colonial impositions, has burst to the fore again —

with a vengeance. This richness brings to mind the days of multicultural

al-Andalus, even if today we would call it multinational or hybrid or cross-

border. For instance, the youngest poet in the last — the Morocco — section

of the book, Omar Berrada, sets his work presented here in the company of

the three international figures whom he honors: the late-nineteenth-century

French avant-gardist Alfred Jarry, the twentieth-century North American

performance poet bpNichol, and the great Sufi poet and mystic Ibn Arabi

( – ), whom we will meet on several occasions throughout “Diwan

Ifrikiya.”

The diwans are interrupted, leavened, given breathing room — however

you experience it — by a series of smaller sections, four “Books” and three

“Oral Traditions,” whose roles are multiple: filling in detail, giving context,

or foregrounding specific areas. Thus “A Book of Multiple Beginnings” pre-

cedes the First Diwan, taking the reader from an early Berber inscription

(see p. ) to a prehistoric rock painting in the southern Sahara’s Tassili and

Hoggar region (see p. ) through the first centuries of recorded literary out-

put. The Phoenician, Greek, and Roman writings from this period include

some of the world-class achievements of Maghrebian culture.

Creation myths and tales of origin logically open this section. This puts

Introduction 7

the autochthonous Berber peoples rightfully at the start of the Maghrebian

adventure while also foregrounding a tradition — the oral tradition — that

has consistently produced major literary achievements over several millen-

nia. This tradition is so ample and important that we had to create three

independent sections (“Oral Traditions – ”) dispersed throughout the

anthology to try to do justice to its richness — which persists today, as the

third of the sections, presenting contemporary oral work, shows. The distri-

bution of these sections also reflects the fact that many of this anthology’s

contemporary writers source and resource themselves in that oral tradition’s

imaginary

— one could go so far as to consider it the Maghrebian collective

unconscious.

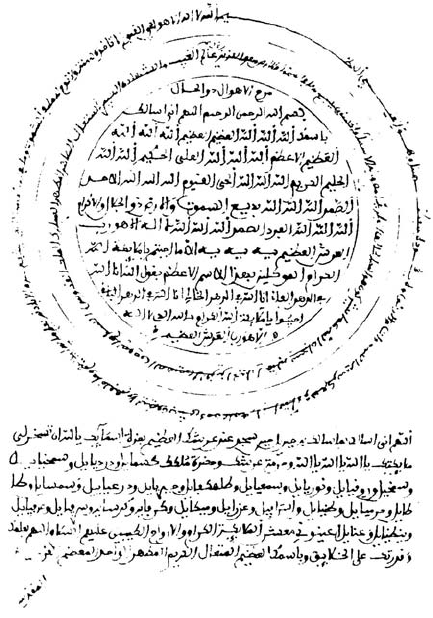

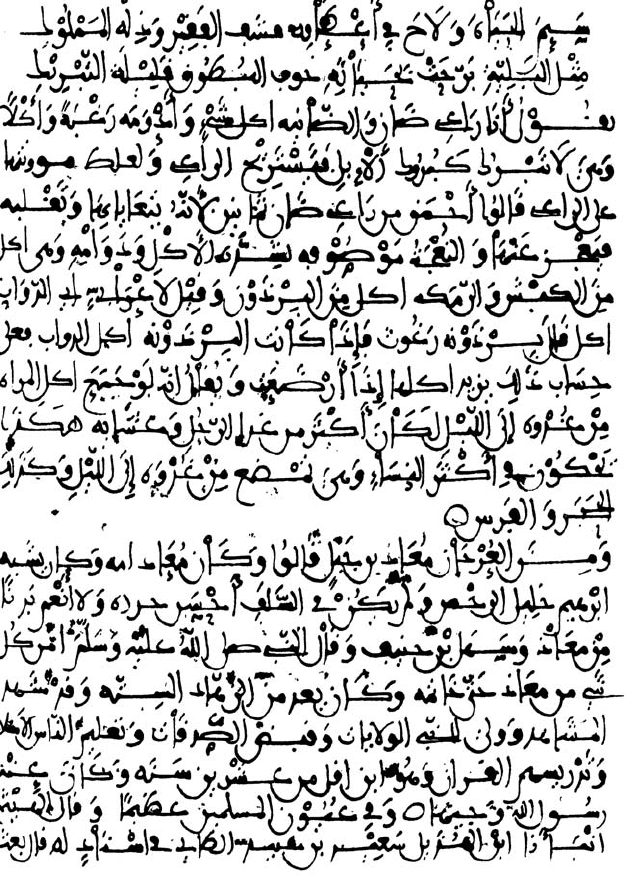

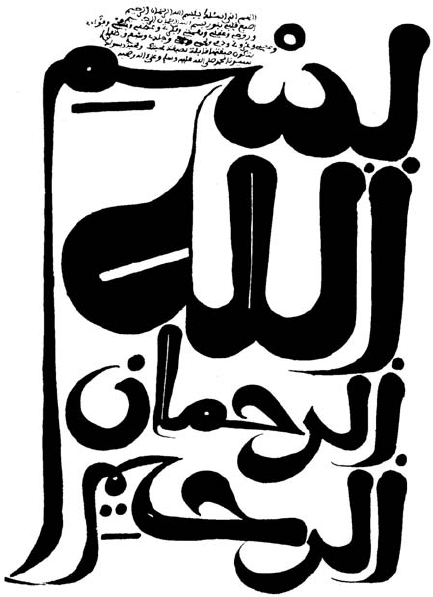

The other books concentrate on the poetry of the Sufi mystics (“A Book

of Mystics”), on the very specific poetics of Arabic calligraphy (“A Book

of Writing”) — a core sense-making, meditative, and aesthetic dimen-

sion of Arab culture — and, finally, on a few diasporic writers (“A Book of

Exiles”), both those who have left North Africa for whatever reason but

feel themselves Maghrebian despite their exilic position and those who have

come and stayed, deciding to become Maghrebian or return to lost roots.

Ironically, this smallest of subsections could be the largest: the diasporic or

exilic dimension is one of the main characteristics of Maghrebian literature,

given that the majority of its authors live and write on two or more shores.

Although it may seem counterintuitive for “A Book of Exiles” to include

such writers as Hélène Cixous and Jacques Derrida, who are seen as essen-

tially French (even if some of their work points to — and their late work

indeed insists more and more on — the importance of their Maghrebian

roots), their contributions here deal exactly with exile from the Maghreb and

the related question of choice of language (see, for example, Derrida’s essay

The Monolingualism of the Other, which is a response to and an elabora-

tion of the Moroccan poet and thinker Abdelkebir Khatibi’s writings on this

problem). Their work also helps to contextualize the problems of the sur-

rounding obviously Maghrebian contemporary writers, who faced both the

necessity of actual exile and the dicult decision of which language to write

in. Although their mother tongue was usually one of several Berber languages

or a darija (dialectal) variation of Arabic, more often than not they forwent

these in favor of either the old colonial language, namely, French, or classical

Arabic (which some Berbers, including even the great Algerian writer Kateb

Yacine, consider as much of a colonial/imperial imposition as French).

Writing in French invariably connects the author with the old colonial

metropole — no matter if he or she lives in the Maghreb or in self-imposed

or forced exile elsewhere

— as that’s where the major publishing houses are

(only recently have independent houses emerged in the Maghreb). Writing

in Arabic means dealing with small local publishers and getting caught up in

8 Introduction

all the political and censorship problems this has meant for most of the time

since independence, or trying to publish in Lebanon or Egypt, the major

Mashreqi publishing centers. The latter is also fraught with problems, as

Maghrebian and Mashreqian cultures do not necessarily coexist easily. But

no matter if they publish in Paris or Beirut, these writers have little chance

of being translated into and published in English. The little interest and

financial support our cultural institutions and publishers have been able to

garner for translations from French and Arabic have been squarely devoted

to Parisian, Beiruti, and Cairene authors. Even greater are the diculties of

those Maghrebian authors who chose to write in Berber

— though Morocco

and Algeria have each recently declared it an ocial national language — or

use the ancient tifinagh alphabet, as does the Tuareg poet Hawad, who now

lives in southern France. It is therefore also an aim of this gathering to pro-

vide a space for the mixing and mingling (at least in English) of writers who

in their own countries and in other (usually country- or language-specific)

anthologies have to exist in a kind of de facto cultural apartheid.

Many if not most of the texts are appearing for the first time in English

translation, while others are retranslations into contemporary American

English of older Englished versions. The genres and the original lan-

guages — Tamazight (Berber), Greek, Latin, Arabic, and French — are mani-

fold. Obviously a work of this order cannot be the work of one or even two

persons. If we are the “author-editors” and, for some part, the translators

of this anthology, we are fully aware of our limits: although between us we

do have English, Latin, French, and Arabic, we do not know all the ages,

all the languages, all the cultures that have contributed to this gathering.

Our role has been threefold: () as the principal gatherers and arrangers of

materials worked on by many other scholars, writers, and translators, () as

the creators of the specific shape this book has taken (although here we owe

a debt to Jerome Rothenberg, the collaborator with one of us on the first two

volumes in the Poems for the Millennium series), and () as the purveyors of

a range of translations done singly or in collaboration whenever no transla-

tions could be found, as well as of most of the contextual materials, such as

prologues and commentaries, given to make more tangible and understand-

able the textual productions — poems, narratives, mystical visions, travel

writings — of an area of the world not necessarily familiar to the general

reader. To keep the volume from being overlong and to maintain focus on

the texts themselves, we have not provided an individual commentary for

every author although in many cases further information is included in

the prologues. We do know the Maghreb well: Habib Tengour is Algerian,

was born and raised in Algeria, taught at the University of Constantine for

many years, and, though now based in Paris, returns to his home country

Introduction 9

and other Maghrebian countries a number of times a year. Pierre Joris also

taught for three years in the s at the University of Constantine (where he

and Tengour met) and has since returned regularly to this book’s three core

countries: Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia.

It is our contention that “Diwan Ifrikiya” is especially important today,

at a moment in history when the West’s, especially the United States’, con-

vulsive engagement with Arab culture is in such a disastrous deadlock.

Paradoxically, the United States is publishing more books on Arab coun-

tries, regimes, economics, and politics than ever before, though nearly all of

them concentrate on the negative and paranoia-creating aspects of “Islamic

terrorism” and do their best to claim noncivilization status for the region

they cover (by suggesting, for instance, that it suers from a combination

of “primitive,” bloodthirsty religion and misuse of modern Euro-American

technologies) or are written from similarly dismissive perspectives. Such

works do not permit the reader to understand what deeply animates these

populations, in truth so near to us yet always pushed back and occulted.

A book concerned with Maghrebian cultural achievements, in fields such

as literature and philosophy, allows us to share in this universe, which is

part of ours, no matter how deeply repressed. Knowledge of the Maghreb

is, we believe, essential in a world where a nomadic mind-set is crucial for

understanding (or inventing) the new century

— especially if we do not want

to repeat some of the deadliest errors of the last.

It is a marvelous coincidence that although we first thought of this book a

quarter century ago, we actually gathered and wrote it exactly when Tunisia

and Libya saw the start of a revolution, called the Arab Spring, that is still

going and may be the shape-shifter that will determine the outcome of this

century. We hope that through its polyvalent view of the region’s cultural

achievements, our book will help to further a deeper understanding of this

strategic part of the world.

Pierre Joris

Habib Tengour

New York / Paris

Spring

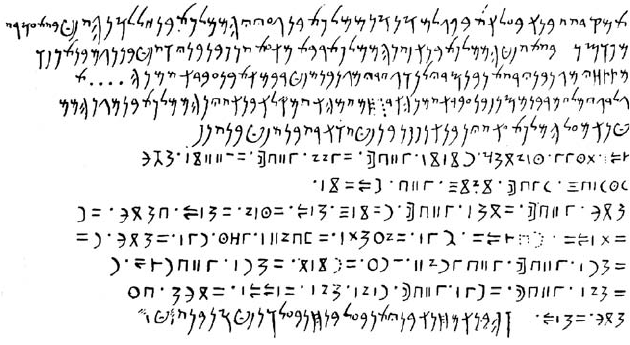

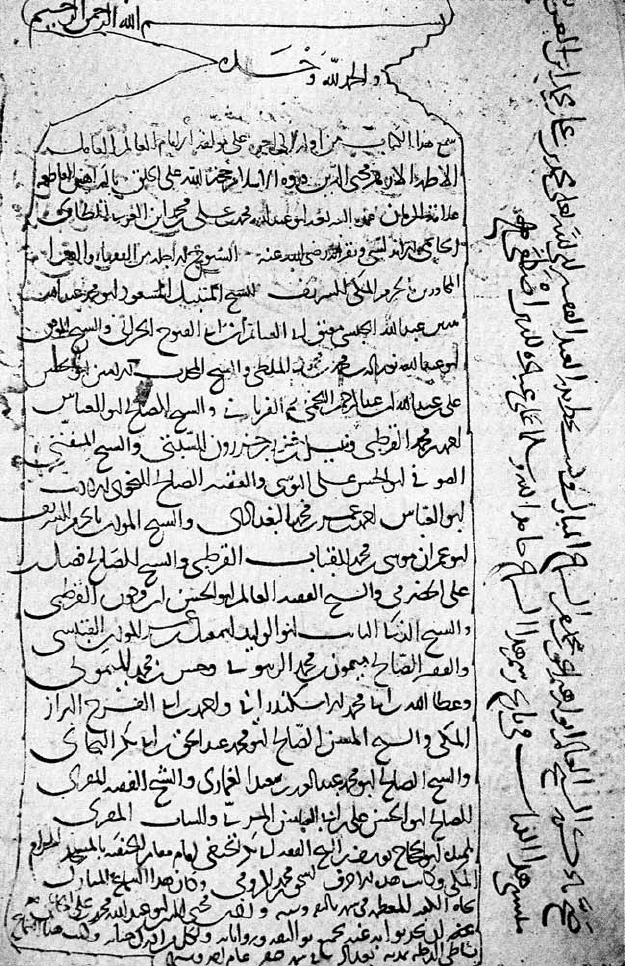

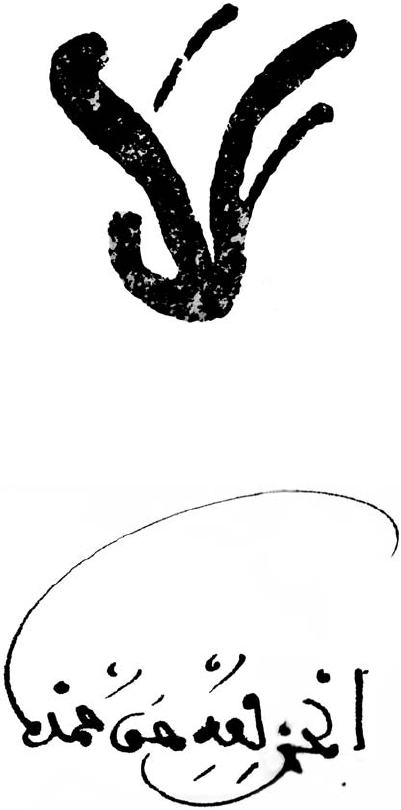

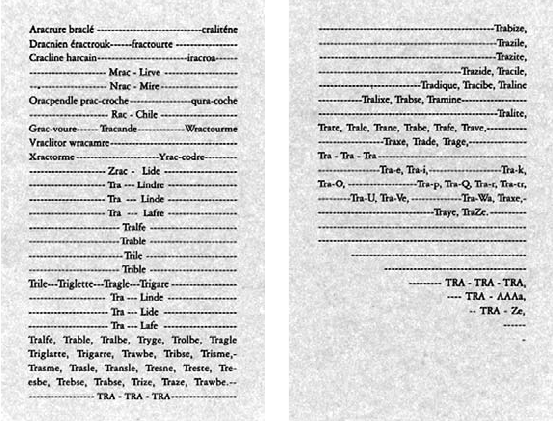

In Thugga, a Berber-Roman city of northern Tunisia, a Punic sanctuary erected and dedicated to the

memory of the Numidian king Massinissa (d. 148

c.e.

), this bilingual inscription in Punic and Lybic-

Berber was found on a rectangular stone in the southeast sector of the forum. Discovered in 1904

and dated to the tenth year of the reign of Massinissa’s successor, Micipsa — that is, to 139

b.c.e.

—

the stone is now at the National Bardo Museum in Tunis.

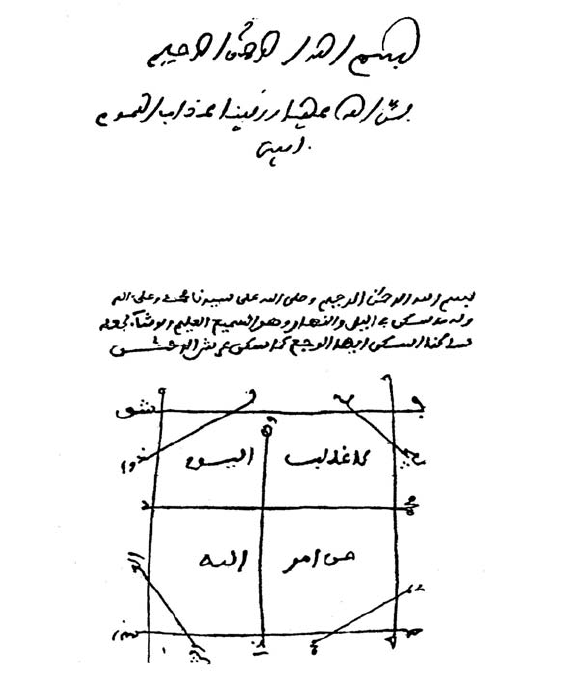

A BOOK OF MULTIPLE

BEGINNINGS

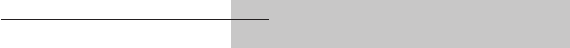

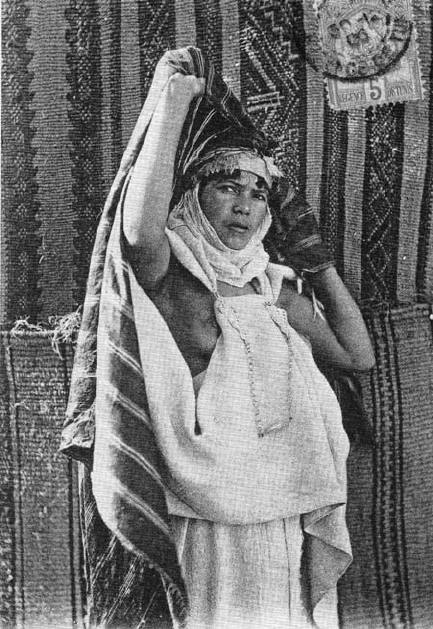

Prehistoric rock painting, southern Sahara Tassili region. From Henri Llote, Vers d’autres Tassilis

(Paris: Arthaud, 1976).

13

() Human traces in North Africa go back to more than , years ...

But our knowledge of them is limited to a specific area: the region of Gafsa

in west-central Tunisia, with ramifications toward the high plains between

Constantine and Sétif in Algeria, and areas of the Sahara and ancient

Cyrenaica — modern Libya. In this region snail farms and a stone and bone

industry were found, indicating that from about until ..., the

human inhabitants seem to have been rather sedentary: they lived on snails,

plants, and wild fruit while also hunting mammals and birds. They had

clearly discovered the concept and practice of art, as shown by the Capsian

tools, worked ostrich eggs, and burned and incised stones found in the quar-

ries of el-Mekta, Tunisia, and preserved in the Gafsa Museum. The Capsian

cultures (named for the town of Gafsa, which in Roman times was known

as Capsa) probably came into being later than those of the Sahara and the

Sudan, which had evolved a Neolithic culture including ceramics by the end

of the seventh millennium ...

At the core of the Capsian Neolithic a range of dierentiations appears,

with each region showing its own characteristics. The definitive desertifi-

cation of the Sahara marked this long Neolithic (lasting from circa

to circa ), creating in its wake a separation between two worlds, one

of which would be forced to turn toward the sea. We know little about

the evolution of North Africa in the second millennium ... Numerous

megalithic monuments, dicult to date with any accuracy, are disseminated

throughout the region around Constantine. They do, however, suggest

Mediterranean influences. The introduction of the horse — which will make

the reputation of the Numidians in their confrontation with the Romans —

also dates from this period.

It is via the Mediterranean that North Africa entered history with a capi-

PROLOGUE

14 A Book of Multiple Beginnings

tal H: the world of writing, of traditions diused over many centuries, and

of archeology, which reveals the ancient presence of the Phoenicians and

the Greeks, from the most eastern parts of what is today Libya to the Pillars

of Hercules. When Elissa (a.k.a. Dido), sister to the king of Tyre, founded

Carthage in ..., the region was peopled by Berbers. The ancient

Greeks called the territory between the Egyptian border and the Pillars of

Hercules, including the Saharan zones, Libya, picking up on the Egyptian

name “land of the Libu.” Homer has Menelaus travel through Libya on his

way home, and according to the poet it was a land of great riches, where

lambs have horns as soon as they are born, ewes lamb three times a year,

and no shepherd ever goes short of milk, meat, or cheese. He called the

inhabitants of this paradisiacal land the Lotophagi, the Lotus-eaters. But

it is Herodotus who has left us the most accurate description of the ancient

Libyan populations: he is the first to clearly establish a distinction between

the nomadic and the sedentary populations. Some of the names he cites have

survived, such as those of the Atlantes (together with the famous legend

of Atlantis), the Auses (Oasians), and, most important, the Maxyes. After

the Roman conquest, Libyan will no longer be the name of all the Berber

peoples, but only one of them.

With the Roman invasion of Africa, “Libya” is divided into four regions:

Libo-Phoenicia, Numidia, Mauritania, and Getulia, the Saharan backcoun-

try. Knowledge of the Berber peoples gets more precise during the period of

Roman colonization, when Roman historians record several traditions con-

cerning the autochthonous populations. The name Mazyes (per Kektaios)

or Maxyes (per Herodotus) is Latinized as Mazaces or Mazax and applied

to Caesarean Mauritania, though by the third century ... several peo-

ples carried this label. The variations on the name probably derive from an

original Berber denomination, as up to today the Berbers call themselves

Imazighen or Amazigh, meaning “free man.” The question of whether they

are an autochthonous population or arrived in that part of the world as a

result of migrations is still sometimes hotly debated.

In De Bello Jugurthino (The Jugurthine War), the Roman historian Sallust

relates the settlement of North Africa according to Punic books attributed

to the Numidian king HiempsalII. To sum up Sallust, this supposedly hap-

pened in three stages. Libyans and Getulians formed the original settlement.

Persians and Medes from Hercules’s army in Spain invaded, finally amal-

gamating via intermarriage. The mix of Persians and Getulians produced

the Numidians, while that of Medes and Libyans resulted in the Moors.

Finally came the Phoenicians, who colonized the shores and founded a num-

ber of cities.

The Berbers emerged from “obscurity” only in the third century ...,

Prologue 15

when the Numidian and Moorish kingdoms got involved in the wars between

Rome and Carthage along the whole perimeter of the eastern Mediterranean.

Previously Carthage had played an essential role in the region’s development

by spreading its customs and adapting them to local circumstances. Punic,

for example, was used by literate Berbers and survived the demise of the

city of Carthage, flourishing side by side with the Berber languages for a

long time. It is interesting to note that despite the existence of an alphabet

of their own, literate Berbers have mostly used the language of the other

(Punic, Greek, and Latin, then Arabic and later French) in their writings.

After Carthage created several commercial centers along the coast of Africa,

its rivalry with the Greeks transformed the habitat, the culture, and the reli-

gious life of this region, primarily from the fourth century ... on. Roman

domination, which eventually stretched across all of North Africa, com-

bined with the Carthaginian civilization’s influence (more or less profound

depending on Carthage’s relation to each city) and the dierent levels of

development of the various Berber populations to create the originality and

the diversity of the North African space. And this was the result despite the

unity that could not but emerge from the centralizing power of Rome

— felt

in, for instance, the Hellenistic and Roman culture dispensed in schools, be

they in Carthage, Cirta, Caesaria, or smaller cities such as Madaurus, where

Apuleius was born.

The economic weight of the African provinces also gave them a certain

cultural leverage. The Berbers were talented practitioners of Latin letters:

Apuleius’s Metamorphoses, a.k.a. The Golden Ass, remains important

to this day, standing as one of the great early prose works foreshadowing

the development of such literary forms as the novel. But it is before all in

the domain of religious thought, with the spreading of Christianity, that

North Africa and specifically Numidia was to make a capital contribution.

Tertullian ( – ..) was the first major Christian author and the first

Maghrebi writer of religious matter in Latin. He opened the way to a wide

literary tradition then developed by Cyprian of Carthage (d. ), Arnobius

(d.), Lactantius ( – ), Optatus of Milevis (d.), and Dracontius

(c. – c. ), whom some claim as possibly the last poet whose mother

tongue was Latin. And then there is of course Augustine, probably the

most illustrious representative of this early North African tradition. Born

in Thagaste (today Souk Ahras) and later made bishop of Hippo (today

Annaba), Augustine marked the consciousness of not only the scholars with

whom he was in contact both in Africa and throughout the Roman Empire

but also those of the following centuries, first with the specific positions

he took on a whole range of theological problems in his voluminous writ-

ings and maybe even more lastingly with his literary-philosophical magnum

16 A Book of Multiple Beginnings

opus, the Confessions. When Augustine died in , the Vandals were at the

doors of Hippo, and North Africa was about to begin another of its many

transformations.

() Even though the earliest literary material traces found in North Africa

are inscriptions, texts, and poems written in Greek, Punic, and Latin, we

contend that the Berbers, the earliest inhabitants of the area, had rich oral

traditions that predated these by millennia. Their tradition of tales, songs,

and other genres — explored in more detail in the three Oral Tradition sec-

tions

— not only has lasted until today but is now experiencing what can

only be described as a renaissance, with present-day Morocco and Algeria

finally inscribing Amazigh as an ocial language in their constitutions, thus

taking the first step toward doing away with the neglect, opprobrium, and

repression that were the lot of the native North African languages during the

centuries of colonial domination — be it Latin-, Arabic-, or French-speaking.

We therefore open the first chapter — called “A Book of Multiple Begin-

nings”—to make clear the multiplicity of the area’s cultural origins ab initio

( with a Berber tale that gives an Amazigh version of how the world and all

that’s in it came to be created). That such tales were gathered in the opening

decades of the twentieth century by Leo Frobenius, whose work — take, for

example, his concept of Paideuma, culture as a gestalt and a living organ-

ism — would be so important to the rich experimental poetic tradition of that

century all the way from Ezra Pound to Jerome Rothenberg’s later ethnopo-

etics movement, seems to us a meaningful link between the most distant

past and our own and may be described by the phrase — in the poet and

cultural passeur Michel Deguy’s words — “extreme contemporaneity.”

The First Human Beings,

Their Sons and Amazon Daughters

In the beginning there were only one man and one woman, and they lived

not on the earth but beneath it. They were the first people in the world, and

neither knew that the other was of another sex. One day they both came to

the well to drink. The man said: “Let me drink.” The woman said: “No, I’ll

drink first. I was here first.” The man tried to push the woman aside. She

struck him. They fought. The man smote the woman so that she dropped to

the ground. Her clothing fell to one side. Her thighs were naked.

The man saw the woman lying strange and naked before him. He saw

that she had a taschunt. He felt that he had a thabuscht. He looked at the

The First Human Beings 17

taschunt and asked: “What is that for?” The woman said: “That is good.”

The man lay upon the woman. He lay with the woman for eight days.

After nine months the woman bore four daughters. Again, after nine

months, she bore four sons. And again four daughters and again four sons.

So at last the man and the woman had fifty daughters and fifty sons. The

father and the mother did not know what to do with so many children. So

they sent them away.

The fifty maidens went o together toward the north. The fifty young

men went o together toward the east. After the maidens had been on their

way northward under the earth for a year, they saw a light above them.

There was a hole in the earth. The maidens saw the sky above them and

cried: “Why stay under the earth when we can climb to the surface, where

we can see the sky?” The maidens climbed up through the hole and onto the

earth.

The fifty youths likewise continued in their own direction under the earth

for a year until they too came to a place where there was a hole in the crust

and they could see the sky above them. The youths looked at the sky and

cried: “Why remain under the earth when there is a place from which one

can see the sky?” So they climbed through their hole to the surface.

Thereafter the fifty maidens went their way over the earth’s surface and

the youths went their way, and none knew aught of the others.

At that time all trees and plants and stones could speak. The fifty maidens

saw the plants and asked them: “Who made you?” And the plants replied:

“The earth.” The maidens asked the earth: “Who made you?” And the earth

replied: “I was already here.” During the night the maidens saw the moon

and the stars, and they cried: “Who made you that you stand so high over us

and over the trees? Is it you who give us light? Who are you, great and little

stars? Who created you? Or are you, perhaps, the ones who have made every-

thing else?” All the maidens called and shouted. But the moon and the stars

were so high that they could not answer. The youths had wandered into the

same region and could hear the fifty maidens shouting. They said to one

another: “Surely here are other people like ourselves. Let us go and see who

they are.” And they set o in the direction from which the shouts had come.

But just before they reached the place, they came to the bank of a great

stream. The stream lay between the fifty maidens and the fifty youths. The

youths had, however, never seen a river before, so they shouted. The maid-

ens heard the shouting in the distance and came toward it.

The maidens reached the other bank of the river, saw the fifty youths, and

cried: “Who are you? What are you shouting? Are you human beings too?”

The fifty youths shouted back: “We too are human beings. We have come

out of the earth. But what are you yelling about?”

18 A Book of Multiple Beginnings

The maidens replied: “We too are human beings, and we too have come

out of the earth. We shouted and asked the moon and the stars who had made

them or if they had made everything else.” The fifty boys spoke to the river:

“You are not like us,” they said. “We cannot grasp you and cannot pass over

you as one can pass over the earth. What are you? How can one cross over you

to the other side?” The river said: “I am the water. I am for bathing and wash-

ing. I am there to drink. If you want to reach my other shore, go upstream to

the shallows. There you can cross over me.”

The fifty youths went upstream, found the shallows, and crossed over to

the other shore. The fifty youths now wished to join the fifty maidens, but

the latter cried: “Do not come too close to us. We won’t stand for it. You go

over there and we’ll stay here, leaving that strip of steppe between us.” So

the fifty youths and the fifty maidens continued on their way, some distance

apart but traveling in the same direction.

One day the fifty boys came to a spring. The fifty maidens also came to a

spring. The youths said: “Did not the river tell us that water was to bathe in?

Come, let us bathe.” The fifty youths laid aside their clothing and stepped

down into the water and bathed. The fifty maidens sat around their spring

and saw the youths in the distance. A bold maiden said: “Come with me and

we shall see what the other human beings are doing.” Two maidens replied:

“We’ll come with you.” All the others refused.

The three maidens crept through the bushes toward the fifty youths.

Two of them stopped on the way. Only the bold maiden came, hidden by

the bushes, to the very place where the youths were bathing. Through the

bushes the maiden looked at the youths, who had laid aside their clothing.

The youths were naked. The maiden looked at all of them. She saw that they

were not like the maidens. She looked at everything carefully. As the youths

dressed again the maiden crept away without their having seen her.

The maiden returned to the other maidens, who gathered around her and

asked: “What have you seen?” The bold maiden replied: “Come, we’ll bathe

too, and then I can tell you and show you.” The fifty maidens undressed and

stepped down into their spring. The bold maiden told them: “The people

over there are not as we are. Where our breasts are, they have nothing. Where

our taschunt is, they have something else. The hair on their heads is not long